The forgotten mapmaker: Nokia has better maps than Apple and maybe even Google

It’s impossible to create a perfect map, but that hasn’t stopped Nokia from trying. Here, we go inside the company’s neverending drive to create a digital copy of the world.

It’s impossible to create a perfect map, but that hasn’t stopped Nokia from trying. Here, we go inside the company’s neverending drive to create a digital copy of the world.

But there are more than two horses in the race to create an index of the physical world. There’s a third company that’s invested billions of dollars, employs thousands of mapmakers, and even drives around its own version of Google’s mythic “Street View” cars.

That company is Nokia, the still-giant but oft-maligned Finnish mobile phone maker, which acquired the geographic information systems company Navteq back in 2007 for $8 billion. That’s only a bit less than the Nokia’s current market value of a bit less than $10 billion, which is down 93 percent since 2007. This might be bad news for the company’s shareholders, but if a certain tech giant with a massive interest in mobile content (Microsoft, Apple, Yahoo) were looking to catch up or stay even with Google, the company’s Location & Commerce unit might look like a nice acquisition they could get on the cheap (especially given that the segment lost 1.5 billion euros last year). Microsoft and Yahoo are already thick as thieves with Nokia’s mapping crew, but Apple is the company that needs the most help.

Business considerations aside, I’m fascinated by the process of mapping. What seems like a rather conventional exercise turns out to be the very cutting edge of mixed reality, of translating the human world and logic into databases that computers can use. And the best part is, unlike web crawlers, which were totally automated, indexing the physical world still requires people heading out on the roads and staring at imagery on computers back at the home office.

As I described last month, Google has spent literally tens of thousands of person-hours creating its maps. I argued that no other company could beat Google at this game, which turned out to be my most controversial assertion. People pointed out that while Google’s driven 5 million miles in Street View cars, UPS drives 3.3 billion miles a year. Whoever had access to these other datasets might be in the mapping (cough) driver’s seat.

Well, it turns out that Nokia is the company that receives the GPS data from both FedEx and UPS, the company’s senior VP of Location Content, Cliff Fox, told me.

“We get over 12 billion probe data points per month coming into the organization,” Fox said from his office in Chicago. “We get probe data not only from commercial vehicles like FedEx and UPS trucks, but we also get it from consumers through navigation applications.”

Depending on the device type, the data that streams into Nokia can have slight variations.

“The system that they have for tracking the UPS trucks is different from the way the maps application works on the Nokia device. You’ll have differences on the amount of times per minute they ping their location, though typically it’s every 5 to 15 seconds,” Fox said. “It’ll give you a location, a direction, and a speed as well.”

They can then use that data to identify new or changed roads. In 2012, they’ve used the GPS data they get to identify 65,000 road segments. (A road segment is defined as the strip of surface between intersecting roads.) The GPS data also comes in handy when they’re building traffic maps because they know the velocity of the vehicles.

(Fascinatingly, one of their consumer privacy protections is to black out every other 30 seconds of tracking information so that the company can’t say “that a particular individual traveled a particular route.”)

In the future, Nokia may be able to extract as many as 30 other attributes from the GPS probe data alone. “That kind of data can help us keep the map more current without having people go out and drive,” Fox said.

But for now, as with Google’s map data “operators,” there is still no better option for gathering data about the physical world than putting a human being in a car and sending him or her through the streets of the world.

***

Meet Tony Cha. He’s a world crawler, a driver of one of Nokia’s “True” vehicles. He’s spent roughly three years on the road, moving from city to city in a modded car that the company’s Chief Technology Officer, Henry Tirri, called “a data collection miracle.” Cha tells me, “You could be gone for months at a time if you’re mapping a big city back east. I live from a hotel. It’s good and bad. You don’t see your friends and family, but the company is expensing your travel.” He’s lucky right now. His hometown of Fresno is his latest collection area. It’ll take a month of driving eight or nine hours a day to complete that city. And then it’ll be on to the next location in Tony Cha’s Neverending Drive.

“It’s kind of surreal. You think, ‘You drove every single street in this city,'” Cha told me. “There are multiple cities where I drove every single street.”

The camera cars work best in dry, temperate conditions, so there’s even a seasonality to the job. The drivers do northern cities in the summer and then the fleet moves south during the winter. Cha gets to follow the good weather.

Within cities, his route is planned by an algorithm that has determined the most efficient way to cover every road on the map. It’s flexible and can accommodate mistakes, but the system “has a specific route it wants you to drive,” he said. He drives for the duration of a work day, then heads to his hotel. The next day, when it’s time to start again, he returns to where he left off and starts again. “I’m almost robotic, in a sense,” he said.

Along the way, he’s seen his fair share of weird reactions to the car. Some people see it and come rushing out of their businesses, so they can be photographed outside. Others flip him the bird. “It doesn’t really bother me,” Cha said.

The car is not inconspicuous. Rising out of the roof, there is a tower of components stacked on top of one another. It folds down for travel, but deployed, it’s probably six feet tall.

The Volkswagen is stocked with $200,000 worth of equipment (that’s Fox’s number) including six cameras for capturing street signs, a panoramic camera for doing Bing Street View imagery, two GPS antennae (one on the wheel, the other on the roof), three laptops, and the crown jewel — a LIDAR system that shoots 64 lasers 360 degrees around the car to create 3D images of the landscape the car passes through.

There is so much data feeding from the roof of the car into its interior that the bundle of cables alone looks like a tank tread. The LIDAR, when it’s switched on, rotates around and emits a high-pitched whine that would probably drive you crazy if someone piped it into your headphones.

The LIDAR is useful for a whole bunch of things, especially when used in combination with the other imagery data. Nokia takes the 1.3 million point measurements per second* that the LIDAR outputs and combines them into what amounts to a wireframe of the street. Then, they drape the imagery they’ve taken with the other cameras on top of that to create a digital representation of a place. Here’s what the process looks like for a spot in Regensberg, Germany, the Agilolfing Tower.

The GIF format reduces the number of colors and detail that the actual cameras have. This is what the actual end product looks like. Feel to click to see a high resolution version.

Once they’ve got a digital representation of a place like this put together, they can do all kinds of data extractions from the images. As you can see in the GIF above, they can determine the height and length of the bridge, reading the physical world itself. And they can decipher human signs that provide valuable clues about the road network. Nokia can extract 100 different types of road signs in 13 different countries automatically. That said, the process is still only about 25 percent automated with a goal of getting to 50 percent; they don’t think it’ll be possible to do much better than that.

***

The biggest mapping problem — the thing that makes Tony Cha’s Neverending Drive necessary — is not dimensions one through three, but number four. The world changes in time.

“To build it the first time is relatively the smaller task compared to maintaining that map,” Nokia’s Fox said.

It’s like that semi-true urban legend about painting the Golden Gate Bridge. They say that they start at one end and by the time they’re done, the spot where they started needs to be repainted. It’s a maintenance loop from which you can’t escape. And it means there is no perfect map. Most maps aren’t even 99 percent accurate, the number that Apple’s been tossing around.

“I’d be shocked [if Apple had 99% accuracy],” Fox commented. “You have real world change. From the time you collect to the time it ends up in a consumer’s hands, there will be more than one-percent change.”

In fact, there might be much more than one percent change, depending on the region. Jacksonville, which isn’t changing much, Nokia “added, modified or deleted geometry” about 6 percent of the road network. In Houston, which is growing more quickly, there were changes to 13 percent of the network. And if we’re talking about Delhi, there were edits to 85 percent of their database.

Now, lived experience tells you that the paths of roads don’t change five or ten percent every year. Many of the changes in the map database are behind the scenes, in the logic of how a road network works or in more subtle data.

“We capture up to 400 pieces of information for every road segment. It could be information about all of the signage, whether or not it is divided road, the number of lanes, where the lanes constrict or expand,” Fox said. “There is just an enormous amount of information. When I’m talking about percentage change, it could be the speed limit or the names that change on specific roads. It’s a never-ending process of understanding the dynamic nature of changes on these road networks.”

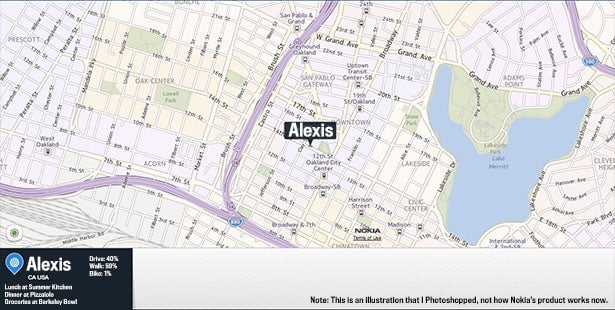

Nokia has a concept they call “The Living Map.” The idea is that as people use the maps — and related location services — the map starts to know what you’re looking for. Searched for Blue Bottle Coffee in San Francisco? Perhaps you’d like to know which Oakland places serve Blue Bottle, too. And bit by bit, you wear tiny little grooves into this giant 3D representation of the entire world, connecting the places that you love together into a new layer that sits on top of all the road network data and Tony Cha’s drives and the LIDAR wireframes. The map will come to life, and you will be in it.

While Cha and I were talking, an unshaven guy in a v-neck t-shirt and sweats walked by and started peppering us with questions. “Do you only come out when it’s a blue sky day?” “Does Apple have street view?” “Can the camera articulate on your rack?” “So you’re directed by software?” This is not uncommon.

Then, out of nowhere, the passerby said, “We’re so close to the day when you can put on VR goggles and literally just walk through the world, anywhere in the world.”

Yes, basically that is the idea: A map of the world that is also a copy of the world.