SpaceX takes its first step toward selling Americans internet from space

SpaceX aims to launch two satellites of a new constellation on Feb. 18, the start of a network it expects to one day include more than 4,000 orbiting spacecraft beaming the internet to customers below—and generating billions of dollars in new revenue for the rocket maker.

SpaceX aims to launch two satellites of a new constellation on Feb. 18, the start of a network it expects to one day include more than 4,000 orbiting spacecraft beaming the internet to customers below—and generating billions of dollars in new revenue for the rocket maker.

Ajit Pai, chair of the Federal Communications Commission, which regulates satellite broadcasts in the US, endorsed the plan to “to unleash the power of satellite constellations to provide high-speed Internet to rural Americans.”

But SpaceX’s chief rival, a satellite company called OneWeb, says CEO Elon Musk’s latest plans are downright dangerous to humans on the ground and spacecraft in orbit, potentially created “for the purposes of delaying and frustrating a competitor.”

Welcome to the friendly race to sell the world satellite internet.

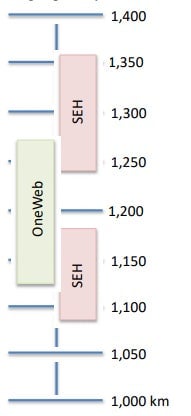

Both companies plan to invest billions in an unproven communications architecture: Rather than a dozen large, powerful satellites broadcasting to Earth from tens of thousands of kilometers away, they will utilize thousands of comparatively small satellites, less than 1,500 kilometers above the planet. The swarming satellites will be able to provide constant, low-latency internet connections to users—if their designers can handle the tricky task of managing the satellites and the signals passed between them and with ground stations below.

This idea had been tried in the 1990s, to resounding failure. Now a new generation of space entrepreneurs thinks that increasingly small and powerful electronics, lower launch costs and growing demand for internet access make a better business case.

Greg Wyler, a telecom entrepreneur who founded another successful satellite company called O3b, is the executive behind OneWeb, which owns key spectrum rights and has the backing of such diverse figures as Richard Branson, Masayoshi Son and Airbus. Wyler and Musk once contemplated working together, but their partnership fell apart and they became competitors.

Wyler’s team argues that it is advantaged by spectrum rights granted by the International Telecommunications Union, a United Nations body that coordinates telecom regulation around the world. It has already won approval from the FCC to offer its service in the US, but it has yet to launch any satellites and reportedly will do so by the end of this year.

Launching the first demonstration satellites is a win for Musk, especially if it allows his company to bring its full constellation, known as Starlink, online earlier. One of the many challenges with these proposals is mass producing the number of satellites required. Wyler had contemplated launching this constellation with Google, but left over concerns about its manufacturing prowess. OneWeb is currently building a satellite factory in Florida, outside of Kennedy Space Center. In putting two satellites into space, albeit for testing purposes, SpaceX is showing off its production chops. (Neither SpaceX nor OneWeb responded to questions about their plans.)

But there’s more than just billions at risk in these projects—debris in orbit already threaten spacecraft, and adding thousands of new satellites could exacerbate the problem if not done carefully. That’s especially true as multiple companies prepare mega-constellations; beyond OneWeb, Boeing, Telesat and Space Norway are considering such schemes.

OneWeb in particular has complained to regulators about the “dramatically increased risk of collision” presented by SpaceX’s plans. In one November 2017 meeting with FCC officials, they portrayed SpaceX as refusing to answer questions about their constellation’s safety, saying it was “most troubled by [SpaceX’s] puzzling proposal to place its constellation in dangerously close proximity to (and interwoven with) OneWeb’s pre-existing constellation.”

Of course, in this case OneWeb means “pre-existing” as approved on paper, not actually in the sky—which underlines why SpaceX’s engineers are so eager to get their satellites up first. The company is counting on its reusable rockets to help it deploy satellites faster than competitors.

In an FCC filing, SpaceX said OneWeb’s concerns were “unfounded” and accused OneWeb of “once again seek[ing] to establish new and unwarranted orbital debris and casualty risk requirements that would also apply to SpaceX—and SpaceX alone.” Ultimately, SpaceX’s filings claim that its system “demonstrated that it will meet or exceed all existing US and international requirements for safety of operations in space and upon de-orbit of satellites.” Given the enthusiastic endorsement of the FCC’s head, it appears the company has at least satisfied the light-touch regulators of the Trump administration.

The move into operating its own constellation is a potentially lucrative one for SpaceX; leaked financials suggest it is counting on the project to generate the enormous amounts of money needed to realize Musk’s dreams of a multi-planetary human civilization.