An anti-Marxist, pro-free speech YouTuber is gaining a following in China

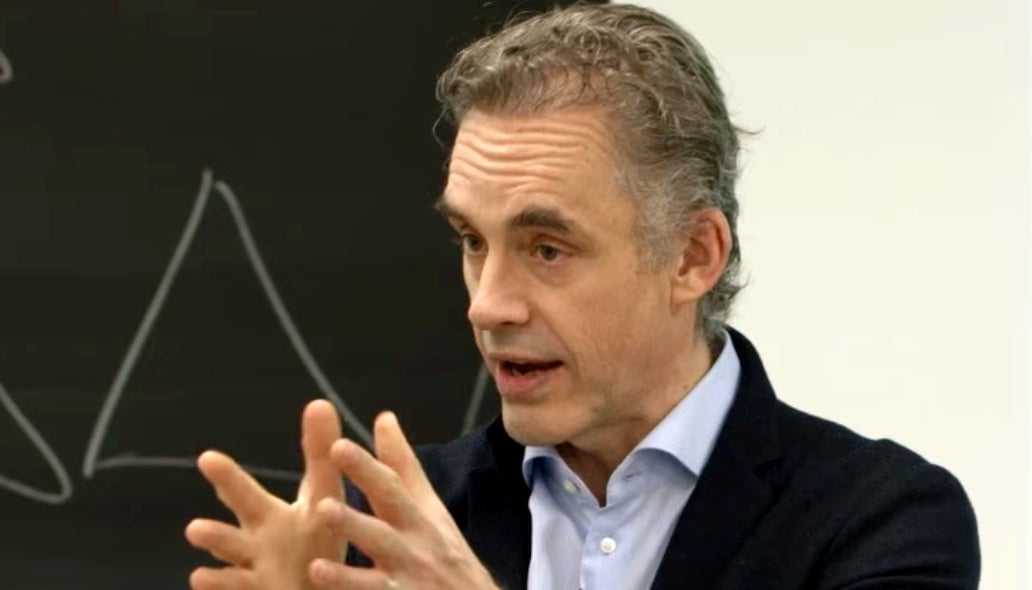

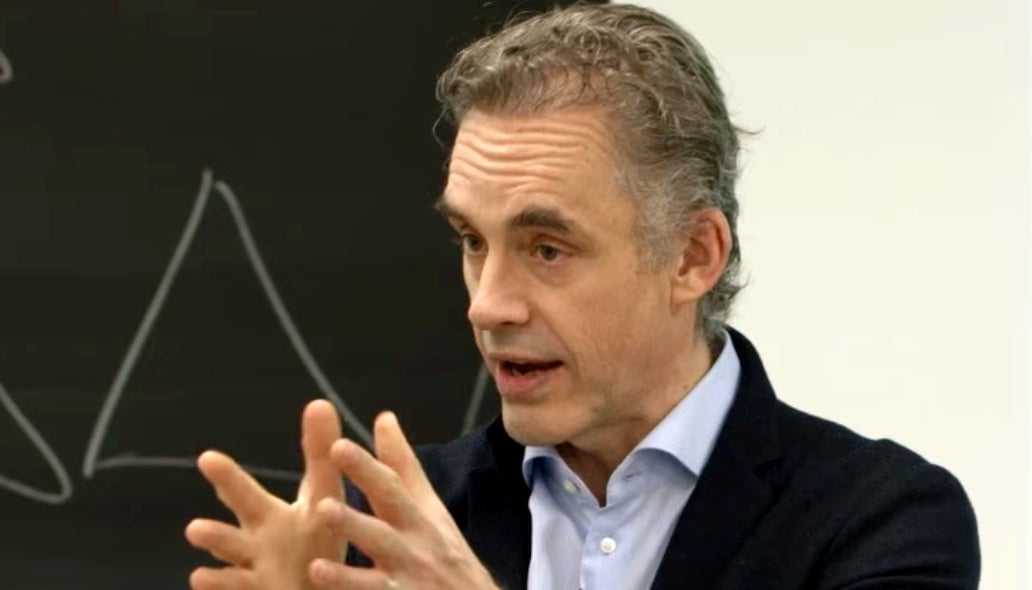

Of all the conservative commentators to rise to prominence after Trump’s election, few are more polarizing than Jordan B. Peterson, a Canadian psychologist and author with a large following on YouTube. Economist Tyler Cowen named him one of the five most influential public intellectuals in the West today. New York Times columnist David Brooks devoted a full column to him (paywall). In a video, Vice described him as “Canada’s most infamous” academic. Noted Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek called his work “ridiculous.”

Of all the conservative commentators to rise to prominence after Trump’s election, few are more polarizing than Jordan B. Peterson, a Canadian psychologist and author with a large following on YouTube. Economist Tyler Cowen named him one of the five most influential public intellectuals in the West today. New York Times columnist David Brooks devoted a full column to him (paywall). In a video, Vice described him as “Canada’s most infamous” academic. Noted Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek called his work “ridiculous.”

Peterson, a professor at the University of Toronto, rose to prominence in late 2016 via a viral video of him voicing his opposition to Bill C-16, an amendment to the Canadian Human Rights Act that added “gender identity or expression” to its list of forbidden grounds for discrimination. Facing a crowd of students, Peterson argued that the bill would compel him to use gender-neutral pronouns to refer to transgender individuals, violating his right to free speech. Some legal scholars have argued Peterson misinterpreted the bill.

Since then Peterson has become an internet superstar among conservatives and libertarians. Yet Peterson is also gaining an audience far away from the Western world that he critiques.

On Feb. 16, Peterson released a YouTube video wishing his viewers in China a happy Lunar New Year. He then extended a personal thanks to Mengjie Ma, a student in Germany, for translating his videos and posting them on Weibo—one of China’s largest social media platforms.

Peterson has indeed made a small splash on China’s internet. Ma’s Weibo page (link in Chinese) has about 28,000 followers, up from just over 1,500 since the time she began translating Peterson’s videos. In particular, her translations of an interview of Peterson on Britain’s Channel 4 went viral, with some clips gathering 20,000 shares. The interview also sparked a lengthy thread (link in Chinese) on Zhihu, China’s answer to Quora. Peterson has scored a deal with Beijing Cheers, a publisher of translated bestselling English-language titles, to release a Mandarin version of his self-help book, 12 Rules for Life.

“I’m usually a pretty lazy and emotionless person,” Ma tells Quartz. “[Peterson’s] lectures of ‘meaning’ and ‘responsibility’ made me rethink my existence and have had a great impact on me.”

The bleeding-heart baizuo

As a cultural critic, Peterson looks at the West—where Black Lives Matter, white privilege, gender-neutral bathrooms, and immigration fears remain pressing and contentious issues. His most frequent target is “political correctness,” which he views as a vestige of Marxism. Peterson is fed up with cultural signals and institutional measures that aim to, in his view, maximize “equality of outcome” for women, minorities, and other groups. (Peterson did not reply to questions Quartz sent to his publicist.)

Yet much of Peterson’s commentary runs parallel to a movement that has long been gestating in China. Over the past few years, the term baizuo—literally “white left”—has become popular among a subset of Chinese internet commenters. The specific meaning of the word is contested. Chenchen Zhang, a Copenhagen-based political theorist who has written about the term and Peterson (link in Chinese), tells Quartz it’s a derogatory term to describe progressives that comes up in discussions about Muslims, immigration, feminism, and multiculturalism, roughly analogous to the term “social justice warrior” (or SJW) in the West.

But baizuo is a bit more loaded than “social justice warrior.” The bai or “white” arguably refers to the white race (others have argued it means “stupid,” riffing off an alternate meaning of the character for bai), while zuo refers to “left-wing” or “liberal.”

Much as the alt-right can couch genuine racism in criticism of “SJWs,” Chinese ethnonationalists can sometimes allude to Chinese supremacy in their criticism of the progressive baizuo. Zhang says that some Chinese people “often talk about the negative impact of the ‘white left’ in civilizational terms.”

“The narrative is that the ‘white left’ are destroying Western civilization and making way for the rule of ‘barbarians’ and ‘backward cultures,’” she says. “Nationalist populists in China also invented new, racialized terms such as huangzuo (yellow left) and huangpibaizuo (yellow-skinned white left) to insult Chinese natives who share the opinions of what they call the white left,” she adds.

Ma says that the term baizuo “has been misused a lot” but says that identity politics remain a serious issue in China.

“For example, when a minority student takes the gaokao [China’s college entrance exam], he or she will get points added. This makes some non-minority students feel unequal,” Ma says, referring to policies intended to compensate (paywall) for economic and educational discrepancies that exist between some minorities and ethnic Han Chinese.

Tensions between the majority Han Chinese and China’s Muslims have also flared over the past several years, Ma adds. “Muslim groups’ power gets stronger day-by-day, and makes many Han Chinese feel threatened. The Han feel that the government will ignore illegal behavior from the Muslims, and this only increases animosity from the Han to the Muslims.” In Xinjiang, violent clashes between Muslims of the Uighur ethnic minority and non-Muslims have led local authorities to ramp up unprecedented surveillance over Muslims there, and severely restrict their movements. Recently, when a Chinese food delivery app added an option to select halal service, social media erupted. Researchers say China’s censorship, which steered the focus of news coverage of the country’s Muslims to favorable government policies, may have fueled resentment among the majority.

Social tensions can play out overseas too, as more and more Chinese nationals work and study in North America and Europe. One Zhihu writer discussing the term baizuo argued that Chinese are unfairly ignored in progressive movements abroad because of white racism, writing (link in Chinese), “On [overseas] campuses there are so many equal rights movements, so why is discrimination against Asians always overlooked? Because unlike other races, despite extreme adversity, Asians defeated Caucasians under tough circumstances. In English, the expression goes ‘beat you at your own game.’” The post received over 3,000 upvotes.

An unusual fit

There’s a certain irony to Peterson’s virality on China’s internet. Peterson liberally uses the terms “Marxist” and “neo-Marxist” liberally to describe his progressive adversaries. Yet for China’s political elite the word “Marxism” is back in vogue.

Meanwhile, Peterson is close to being a free-speech absolutist. In China, his videos are going viral on WeChat and Weibo, platforms that are closely patrolled in accordance with China’s strict censorship norms. YouTube, the site most responsible for Peterson’s fame, remains blocked in China by the “Great Firewall”—to the annoyance of some, but to the overwhelming indifference of many Chinese. Christianity is also a common theme in his lecture. Yet China’s ruling party has long suppressed freedom of speech and religion, particularly under Xi.

What’s less clear is how the Chinese Communist Party views progressive movements focused on race, gender, and sexuality inside and outside its borders, as well as any backlash against them. Last year, in its annual response to the US human rights report on China, China detailed racial discrimination against black people in 2016, including a list of deaths of minorities at the hands of police, the original spark for the Black Lives Matter movement. On social media, meanwhile, China has alternately fanned and cracked down on nationalist sentiment, while also censoring progressive waves such as the #MeToo outpouring. Both, when taken to the extreme, can threaten the public’s faith in the party.

Ma’s doesn’t see Peterson as a figurehead for the anti-baizuo movement, but someone who encourages people to see others as individuals, rather than members of groups. Yet she says that Peterson’s free-speech, anti-Marxist stances have made her more cautious. “I’ve been somewhat careful of my safety, because I don’t know how high the authorities’ tolerance is for what I’ve been doing,” she says.

Image by Adam Jacobs on Flickr, licensed under CC-BY-2.0.