Days ago, desperate African migrants painted their faces white in the hope that Israeli officials would treat them with more humanity.

It was the latest act by Eritreans, Sudanese and other African migrants protesting their deportation from Israel in a system that has refused to make any room for them, describing the thousands of Eritreans and Sudanese who fled war as “infiltrators.”

While studying abroad at Tel Aviv University, Canadian artist Alicia Mersy was inspired by the drive and grit of African immigrants to make a life in Israel. Mersy’s work offers a glimpse into the spaces where immigrants create a community and let their guard down.

Using photography as an excuse to get close to people and digital tools to go beyond documentary, Mersy’s work delves into the uncomfortable questions raised by Israel’s policies. The subjects of her work are by no means passive, and their visual representation challenges the negative stereotypes of African immigrants in Israel.

“My intentions were clear: I wanted to talk about Israel’s so-called open society and expose their institutionalized racism,” she says.

Quartz: In Diaspora Brilliance, why did you choose to look at the material success of immigrants through cellphones and cellphone shops?

Alicia Mersy: In Tel Aviv, those stores are very important to the African community because phones are how they keep in touch. I liked phones as a symbol for how technology allows you to get out of your physical space, when you’re an asylum seeker it has a much deeper meaning—in a way the phone itself is a refuge and a survival tool. They use technology in order to make their journey safer and share life or death information but also to show their family they are OK.

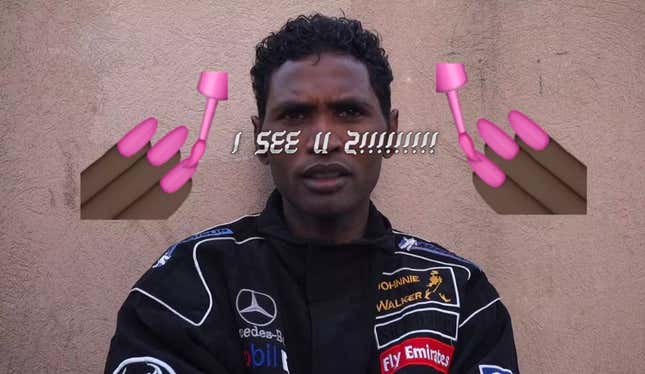

In the installation You Thrive Cause You Must, did you really put the images up all over Tel Aviv? What was it about the studio photo framing that appealed to you for this particular project?

You thrive cause you must started when I heard that the Tel Aviv museum was going to have an exhibition about Africa. I met with the curator and told her I thought it would be important to include the local African community. I introduced her to Sol Digital Studio, a photographic business based in South Tel Aviv, which has been photographing Tel Aviv’s Eritrean Community since 2013.

I was interested in Abiel’s studio because of how he is using aesthetic tools to show survival and how he is empowering and representing his own community. In his photos, these men are performing success. It’s their own representation; their own decisions, their own styling, their own art direction.

I used his portraits and added some quotes from conversations I had with the clients of his store. The flags were brought all over Tel Aviv in different locations. The reactions varied depending on the neighborhoods. Most people reacted in a very positive way, very few were shouting and angry.

Why do you situate your work in the businesses of immigrants, describing them as “places of healing?”

I feel that these businesses show how they created a situation out of the nothing and how powerful that is. They reflect the bravery of being alive. Like you and me they just want to live, build their business, have fun and be free.These businesses are where immigrants hang out because thats where they feel safe. In Not White Not Jewish and Don’t Believe in Color, Believe in Business I wanted to show the immigrants’ opinions on the Israel society (and not the other way around).

These are places of healing in the sense of the salon being a safe space for women to be who they are without fear of being assaulted. Aside from treating oneself to the pleasure of renewing your hair, taking care of oneself, it is a place for reunion and chatting—that’s healing! Often in the back of their business, there are more businesses like restaurants and coffee shops where they sit down, drink tea, smoke shisha. They are like those removed secret spots away from their marginalizing society where they are free to talk about politics, love or just pray quietly, creating their own autonomy.

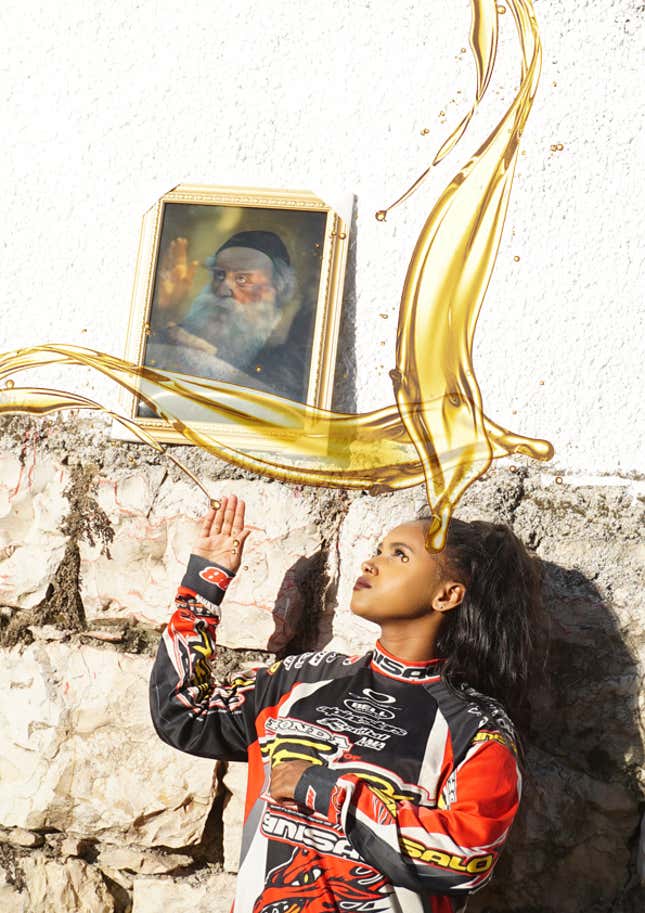

Xenia seems like a departure from your previous work, why did you choose a product as the central point of this piece?

On Jan. 1 Israel’s Interior Ministry, announced plans to detain or relocate thousands of Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers to an African country, if they refuse to leave voluntarily by March 2018. I made Xenia on that day and sent it to my friends in Tel Aviv. Xenia [based on an ancient Greek concept of “guest-friendship” based on generosity, hospitality and courtesy] is a video promoting an anti-detention and ant-deportation serum. The serum is a gesture to show citizens care and support their life and hard work.

As an artist living and working in cities like Tel Aviv and Ramallah, do you feel an added responsibility to explore the areas fraught politics? Do you find that it is something that is unavoidable?

I lived in Israel for two years and I’m about to go in March to visit and to finish a film I started last year with [Palestinian political activist] Marwan Barghouti’s family in Ramallah. I’m trying to bring information to people that don’t have access to the information im privileged to have. I dont know if I’m in the right place to say ‘You have to care and trust each other because the situation is so fucked up.’ I guess what im trying to do with my art is say ‘Here is some things you should look at that might change you opinion of one another.’

These answers have been edited for brevity.