In March 1971, Tina and Ike Turner and Wilson Picket arrived in Accra, Ghana to play an epic 15-hour Independence Day concert. As they and other African American musicians stepped down from the plane, a huge crowd surged around them. There were drummers and dancers. A wulomo—the city’s high priest—dressed in all white, poured libations to welcome “America’s most soulful performers” to their ancestral home. Tina waved to the crowd. A film crew captured the whole show. It was quite a welcome.

Back on the plane, dozens of white musicians waited, sweating in the tropical heat. They weren’t going anywhere until the film crew was finished.

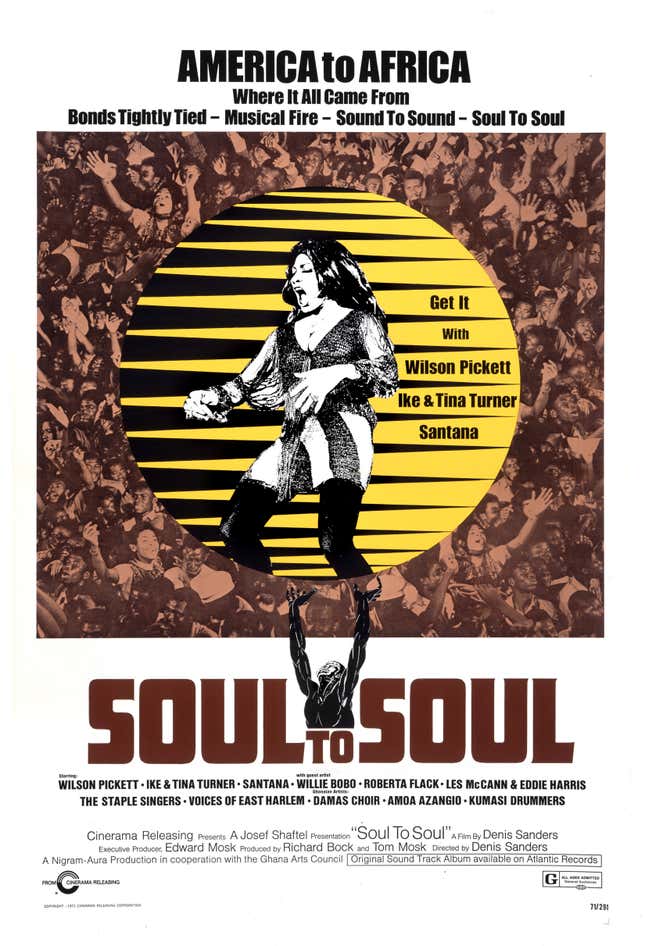

The scene at Accra airport would become part of Soul to Soul, a documentary movie that captured the concert of the same name. It promised the unprecedented experience of watching prominent black Americans visiting Africa for the first time, just 14 years after Ghana won independence from Britain. According to the film’s PR people, this was a big deal: famous American musicians never toured Africa.

There was actually nothing unprecedented about any of this. Maya Angelou, who’d lived in Ghana several years prior, originally proposed the idea of holding a festival of black American music in Ghana (Angelou was reportedly involved with the production of Soul to Soul, but not credited.) And when the lineup was first announced, people were underwhelmed.

James Brown, then at the peak of his powers, had just toured Africa, but skipped Ghana. This was seen as an insult. Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud, had been released four years earlier and people were still yelling the words at each other across streets all over the country. (James Brown, along with Fela Kuti and Aretha Franklin, reportedly declined invitations to perform in Soul to Soul.) Tina Turner and Wilson Pickett were massively popular. But even the Soul to Soul producers billed Pickett as “Soul Brother No. 2,” in deference to James Brown.

The show also featured the Staples Sisters, Santana (who played with the drummer Willie Bobo,) Roberta Flack, Voices of East Harlem, Les McCann and Eddie Harris, as well as local musicians like Kwaa Mensah, Charlotte Daddah and the Magic Aliens. It was a remarkable event. It’s still remembered fondly. But it was not the ground-breaking, world-changing night it wanted to be.

Here, on the 47th anniversary of ‘Soul to Soul’, is an account of the festivities, culled from newspapers, magazines and people who were there.

It all started in 1970. A wealthy Hollywood attorney named Ed Mosk, his wife Fern and their son Ted were trying to get a film adaptation of Chinua Achebe’s ‘Things Fall Apart’ off the ground. Ted came up with the idea of a West African Woodstock.

The United States can have its Woodstocks and Britain can have its Isle of Wights — our answer to these pop festivals is the Black Star Square and its Soul to Soul. - Daily Graphic (Ghana)

In the weeks before the show, there were ads in the newspapers begging Ghanaians to turn up at the airport to meet the stars. Most of the musicians were said to be “visiting Africa, their ‘roots,’ for the first time.” The producers of Soul to Soul were desperate for a crowd. They seemed to want to recreate Louis Armstrong’s iconic visit to Accra in 1956. More than 10,000 people greeted him on the tarmac. A dozen bands struck up E. T. Mensah’s ‘All For You.’ Armstrong recognized the old calypso melody, whipped out his trumpet and played along. The Soul to Soul performers were met by a good—if less effusive—crowd, and spent their first few days in Ghana sightseeing.

Meanwhile, locals prepared for the all-night show.

“If you do not intend making it solo, do not get a partner who will bog you down. You want to live it up and he (she) wants to just sit and listen; you want to stay all night and he (she) wants to leave at 1 a.m. by jove your night is messed up.” – Daily Graphic

It was scheduled for Independence day, Mar. 6, 1971. On the day of the show, people started arriving at Black Star Square hours before the advertised start at 3 pm. They needn’t have bothered: because of a series of technical issues, the show eventually started at 5.30 pm.

Around 100,000 people had paid for tickets, including Nii Sei Oboade, who was 18 at the time. She remembers a lot of excitement about the show. People were coming from all over the country, and she and some friends made plans to sneak out for the all-night concert.

Others, like Ghanaian journalist Cameron Duodu figured out other ways to take in the show. “I parked my car, with most of my family in it, near the Square, at the High Street end. The spot I picked was extremely good: a very faithful loudspeaker had been attached to a lamp-post.”

In the square, the audience was subdued.

The Voices of East Harlem delivered a brilliant, high‐energy set, all curiously ended by one salvo of applause and then silence… And so it went. - New York Times.

I sat tapping my feet,’ said one American ‘feeling so good to hear sounds that were so close to me. But on the other side of me, there sat an African Boy Scout… moving not a muscle. It must be the British influence. – Ebony magazine

Nii Sei Oboade remembers it differently. By the time the show really got going, it was late. And because Black Star Square—now known as Independence Square—is an exposed parade ground right on the shore, it was cold and windy.

In fact, it was so windy the sound from the show carried right across central Accra: “The speakers were everywhere so even if you were not close to the stage – because of the direction of the wind, even if you were somewhere in Oxford Street [about a mile away] – you could hear it,” she said. “Of course, Accra wasn’t as crowded back then.”

The audience was also a little bored. Oboade says she was really only there for Tina Turner and Wilson Pickett, who were among the last acts to perform.

“Midnight approached. Ike and Tina went to work. The Ikettes, like something out of a comic book or science fiction, flashed forth from the wings, all a‐twitch in white, fringed minis, and seemed prepared to have it all out right there. – New York Times

Tina Turner seemed determined to get the crowd moving, and at one point, told them off. The crowd finally perked up after about 2 a.m., as she performed ‘Proud Mary,’ ‘Honky Tonk Woman’ and ‘River Deep.’ Daily Graphic thought they were fantastic and described them as the “surprise packet” of the show.

Then came the man at the top of the bill. Wilson Picket, dressed in a black bodysuit, led with ‘Midnight Hour,’ and his trademark scream. The crowd went wild. Some, close to the front charged the stage to dance with Pickett.

The crowd stayed until almost seven in the morning. The film was released in August 1971. It never recovered its costs, but later became something of a cult classic. The Mosks’ adaptation of ‘Things Fall Apart’ fell apart. The few people who saw it said it was a strange hash of three Achebe books. It was never released.