How cigarette companies use free trade deals to sell more cigarettes to women and kids

Global trade negotiations in Washington this week will determine how cigarette companies will be able to market their products in developing nations—and potentially, overturn smoking restrictions around the world.

Global trade negotiations in Washington this week will determine how cigarette companies will be able to market their products in developing nations—and potentially, overturn smoking restrictions around the world.

As cigarette smoking has fallen in the United States and Europe thanks to public health laws and liability lawsuits, global tobacco companies have increasingly turned to developing markets to expand their business. Now they’re trying to make sure the largest trade agreement since the World Trade Organization gives them the tools they need to stop those countries from adopting the laws that cost them customers in wealthier nations.

“It is very important for people to understand that the industry is using trade law as a new weapon, and [the Trans-Pacific Partnership] provides an opportunity to put a stop to that,” Susan Liss, the executive director of the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, says.

Like everyone else, cigarette companies turn to emerging markets

Smoking rates are plunging in the US—from 25% of the population in 1990 to 19% today—and similar drops are happening in the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada. Today, of the world’s growing population of 1.3 billion smokers, 80% reside in low or middle-income economies. Tobacco companies naturally want to make sure they can protect and expand their businesses in those markets, especially among women, who have much lower smoking rates than women in wealthier countries.

Until the late 1990s, the US government was keen to help American tobacco companies accomplish this end, threatening trade fights with Japan, Thailand, Taiwan and South Korea unless they opened their borders to US cigarettes and their sophisticated marketing campaigns. A government study found that in the year after US companies entered South Korean markets, smoking among teenagers surged, especially among young women, where the share of smokers increased from 1.6% to 8.7% in just one year.

Public health and development organizations decry the expansion of smoking in these countries, fearful not just about the death rate—the World Health Organization estimates that one billion people will die from smoking this century—but also the secondary costs. Those include money spent by the malnourished and poor on cigarettes rather than staples, agricultural labor diverted to inefficient tobacco farming rather than food or other enterprise, and the costs of health care for the myriad ailments associated with cigarette smoking and second-hand smoke. The face of these fears is a chain-smoking Indonesian toddler:

A new way to challenge anti-smoking laws

The US public turned against the tobacco industry during the 1990s after a series of lawsuits revealed that the companies knew about tobacco’s health risks and led to a $200 billion national settlement. In 2001, US president Bill Clinton signed an executive order forbidding the US government to advocate on tobacco’s behalf. To help reduce legal risk, many cigarette companies spun their international operations out of the US, most notably with Altria’s decision to create Phillip Morris International in Switzerland, which now controls about 16% of the world market share outside of the US, with major emphasis on Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan and China.

Absent state intervention on their behalf, tobacco companies found a new way to fight efforts to regulate tobacco marketing. They take advantage of an “investor-state” dispute options being built into more free trade agreements between countries, which allows companies to directly challenge regulations they believe discriminate against foreign products. Unlike fighting laws in domestic legislatures or through WTO disputes, which are more formal and predictable, investor-state conflicts are decided by a panel of international arbitrators with no appeal, making them more attractive to multinational corporations.

“In most cases, when tobacco companies have gone after developing countries, they’ve gone after them for the same type of regulations we have in the US,” Thomas Bollyky, a former US trade negotiator, says. ”They have made use of the possibility to bring disputes under trade and investment agreements in a way that no other industry has, and threatened disputes against Togo and Namibia, countries that don’t really have a budget set aside to fight these disputes, let alone the personnel to do it.”

PMI has used that tactic to challenge Australia’s proposed “plain” packaging rules, which would eliminate bright colors and branding on packs and cartons, and Uruguay’s plan to require 80% of cigarette packs be covered in warning labels. The company argues that these restrictions on its trademarks and branding are akin to expropriation (which would require the country to pay the restricted company for selling its product unbranded) and violate trade deals between Australia and Hong Kong, where PMI has a subsidiary, and Switzerland and Uruguay.

The TPP-Tobacco collision

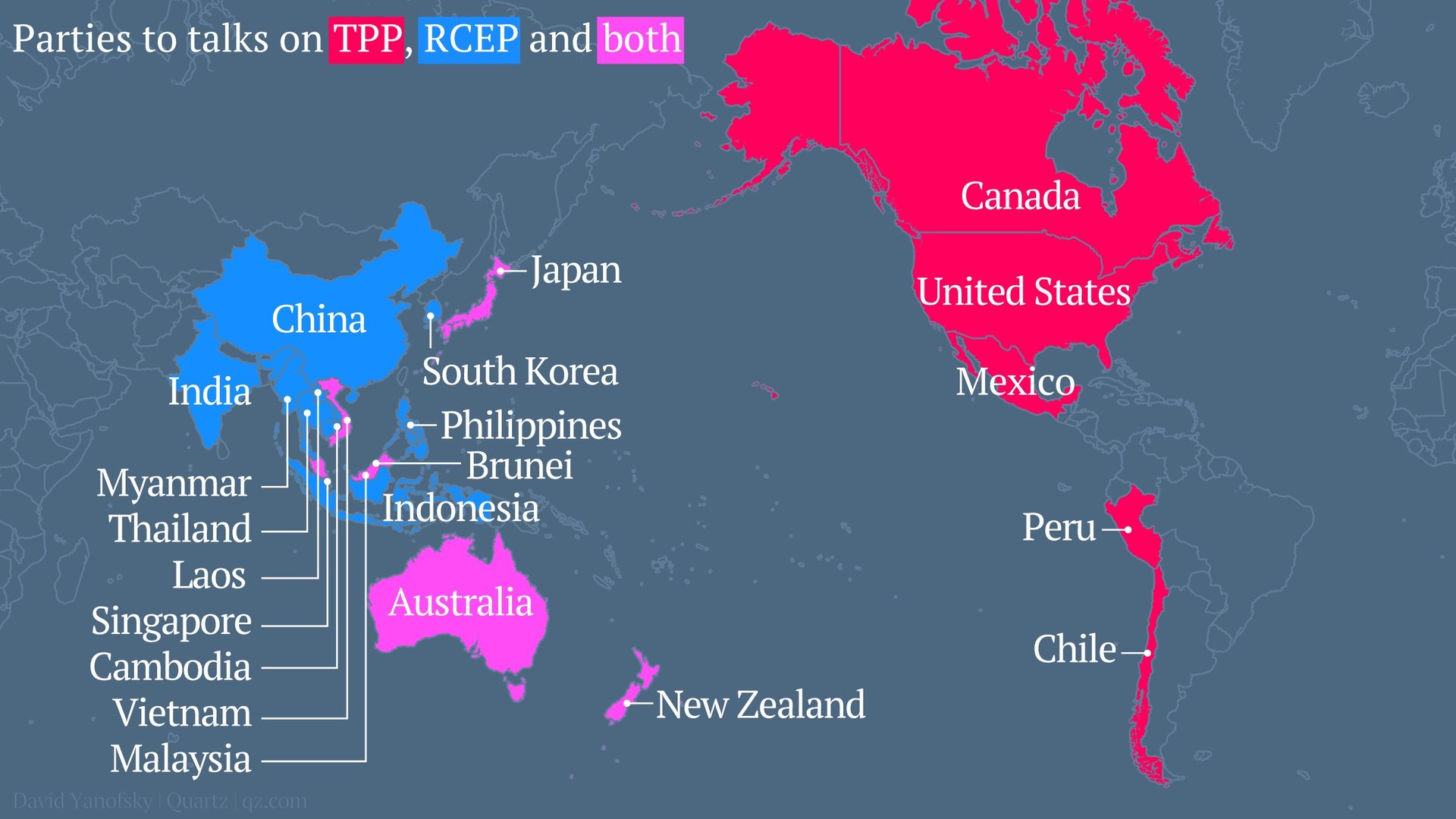

The Trans-Pacific Partnership aims to include twelve countries along the Pacific Rim in a massive free trade agreement; with this summer’s addition of Japan, it would be the largest trade agreement since the WTO was formed in 1995. Along with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), it’s part of a new push to liberalize trade in the Pacific:

Formal negotiations have been going on all summer, including this week’s meetings in Washington, with the aim of completing an agreement in time for US president Obama’s October visit to the Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in Bali. The deal would include a framework for investor-state disputes that could allow tobacco companies to expand their fight against smoking restrictions into the 12 TPP countries.

For public health advocates, that raises two ugly possibilities. One is that some of the poorer countries involved in the TPP may not be prepared to fight these kinds of disputes, because they lack the budget, lawyers and international experience. That makes it harder for governments to support new public health laws, especially those that already conflict with local preferences and entrenched interests. The other worry is that the tobacco companies could use the disputes to challenge the laws already passed by wealthier nations. “U.S. federal, state, and local laws include many of the same regulations that the tobacco industry has challenged in Uruguay, Norway, and elsewhere,” Bollyky says.

How will the negotiations end?

Malaysia, where there is a strong anti-smoking movement, has proposed that tobacco be removed from the deal, so the TPP countries can apply restrictions without violating the terms of the partnership, a move also supported by anti-smoking advocates. Bollyky argues that a broad public health exemption for tobacco products should be included in the bill, following the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control, an international treaty signed by 176 countries. This would allow countries to pass anti-smoking measures without fear of challenge as long as they don’t blatantly favor domestic producers.

The US initially released a proposal to create a specific safe harbor for anti-smoking laws in the TPP, but then walked it back to a more general public health standard that still leaves room for tobacco companies to bring disputes. While this partially reflects the still-considerable political clout of the shrinking US tobacco industry, the bigger fear in the business community is that it will open the door to safe harbors for other controversial products like alcohol, genetically-modified crops and sugary soft-drinks.

Anti-smoking groups argue that this fear is misguided and that tobacco is uniquely pernicious, but all sides agree that the decision made this week is of major importance. First, the TPP will be “dockable”—in other words, once it is ratified, new nations can join easily by agreeing to its standards, and many expect other nations, including South Korea, to join and expand the bloc. Second, it will set the bar for future free-trade deals, including the agreement under discussion between the US and the European Union.