Obamanomics meets Abenomics

Japan will join negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade deal that would encompass 12—and possibly 13—important economies around the Pacific Rim, including the United States, Mexico, Malaysia and Vietnam. Japan’s inclusion, due to a bilateral accord with the US reached last week, could be very significant if an agreement can be reached.

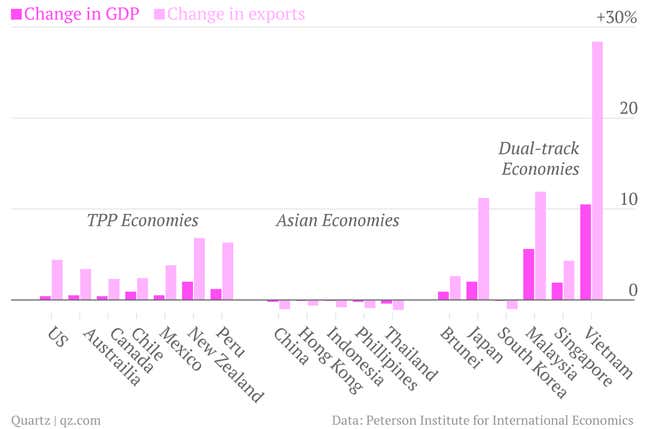

Putting some substance in America’s Pacific pivot. There’s a reason that President Obama’s national security adviser was trumpeting the plan in an op-ed yesterday: It’s one of the major pillars of the administration’s so-called “pivot” to Asia. As US trade expert William Frenzel put it, the TPP started off as “Snow White and the seven dwarves”—the United States and many smaller economies, and eventually Mexico and Canada, two larger economies already in free-trade pacts with the US. The addition of Japan, the world’s third-largest economy, is a much bigger deal, in part because it has some of the tightest restrictions on imports in the world. The move triples America’s expected income gains from the deal, according to a model developed by the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Look at the losers. The Asian economies who aren’t part of the deal, lead by China, would lose out thanks to trade heading to other countries. That’s one reason that China is anchoring a rival proposed trade pact, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, that also includes many of the TPP countries. Experts say the competing talks could spur free trade in the region. Among the dual-track nations, Vietnam in particular is expected to make out very well, as a reduction in trade barriers allows it to accelerate efforts to replace China and other Asian countries as a leading exporter of goods such as apparel and footwear. South Korea isn’t part of the talks, yet, but because it recently agreed to free trade with the US, many expect it will seek admission to the pact if it is completed.

It’s Abenomics in action. Our graphic explaining the logic behind Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s plan to revive his country’s troubled economy made mention of plans to improve Japan’s export sector through structural reform, and this is one of those opportunities. The country could gain a 2% boost in GDP, worth some $104.6 billion, a year after the deal goes into effect. While some see the US-South Korea economic pact as a major incentive for Japan joining, Frenzel points to Abe’s election and subsequent visit to the US as a turning point. “Abe has convinced us he has enough horsepower to get the thing approved in a pretty pristine manner,” Frenzel says. “Japan knows it has got to put agriculture on the table, at least a big part of it, to get into the agreement.”

Can a deal be reached? The biggest problem with the accord in Japan, of course, is that agriculture is on the table, and Japan’s agricultural sector is highly protected from foreign competition. While manufacturers generally support the deal, the country’s automakers are also concerned that South Korea got a better deal with the US on tariffs that raise the cost of selling cars in America. In the US, Democrats and automakers alike have questioned whether Japan is serious about opening its markets, especially those who see its agressive monetary policy as currency manipulation. One bigger problem? President Obama doesn’t have a chief trade negotiator approved by the Senate since his last trade representative stepped down, and getting nominees appointed in a timely way has proven a major challenge throughout his term.