When daylight saving time was put to a vote

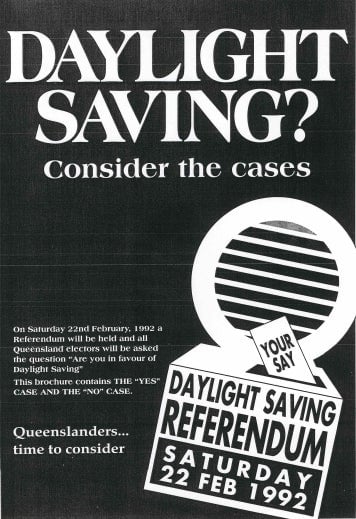

In 1992, the people of Queensland, Australia were posed the following question: “Are you in favour of daylight saving?” The answers would decide the future of time in the state.

In 1992, the people of Queensland, Australia were posed the following question: “Are you in favour of daylight saving?” The answers would decide the future of time in the state.

Queensland, which didn’t have daylight saving time, had just undergone a three-year trial of pushing forward their clocks an hour during the summer months. It was only intended for one year. But the task force assigned to monitor the experiment thought it would be best for it to go on for another two years, and then for a referendum to be held.

People were divided. The arguments for and against daylights saving were basically the same ones people have had the world over since Germany became the first country to adopt the practice about 100 years ago, during the first World War.

Those in favor argued that later daylight hours in the summer would be good for the economy and public health (pdf). More sunlight after work leads to more shopping and people doing recreational activities outside. It would also decrease energy use, they said, because people could use more natural light in the evening (research suggests the actual impact on energy usage are minimal).

The majority of supporters came from the densely populated south-eastern corner of the state, where Brisbane, Queensland’s largest city, is located. It is also the area of the state where the sun goes down earliest.

Those against daylight saving were concentrated in the western parts of the state, where the sun already went down later in the day. These clock-changing skeptics argued that the limited benefits of daylight saving almost entirely accrued to southeasterners, and that they were not worth the disruption caused by time changes (some research does suggest daylight saving leads to health problems and lower productivity). They also complained that children in the western portion of the state would have to travel to school in darkness because of the change.

In the end, Queenslanders rejected daylight saving 54.5% to 45.5%.

Results of 1992 Queensland daylight saving referendum

The geographical rift in the vote was similar to that of the UK’s Brexit vote and US’s 2016 presidential vote. In some metropolitan districts in the southeast, more than two-thirds of voters wanted daylight saving. In many western districts, like Charters Towers and Cook, more than 80% voted no.

To this day, Queensland does not have daylight saving time. The fight is not over, though.

In 2008, the Daylight Saving for South East Queensland Party was established to advocate for a separate time-zone for that part of the state. The party’s candidates received more than 22,000 votes (pdf) in the 2009 state elections (almost 1% of the total vote). While the party has since disbanded and morphed into lobbying group, it is still pushing for a change.