This is probably the last bit of good economic news to come from Turkey for a while

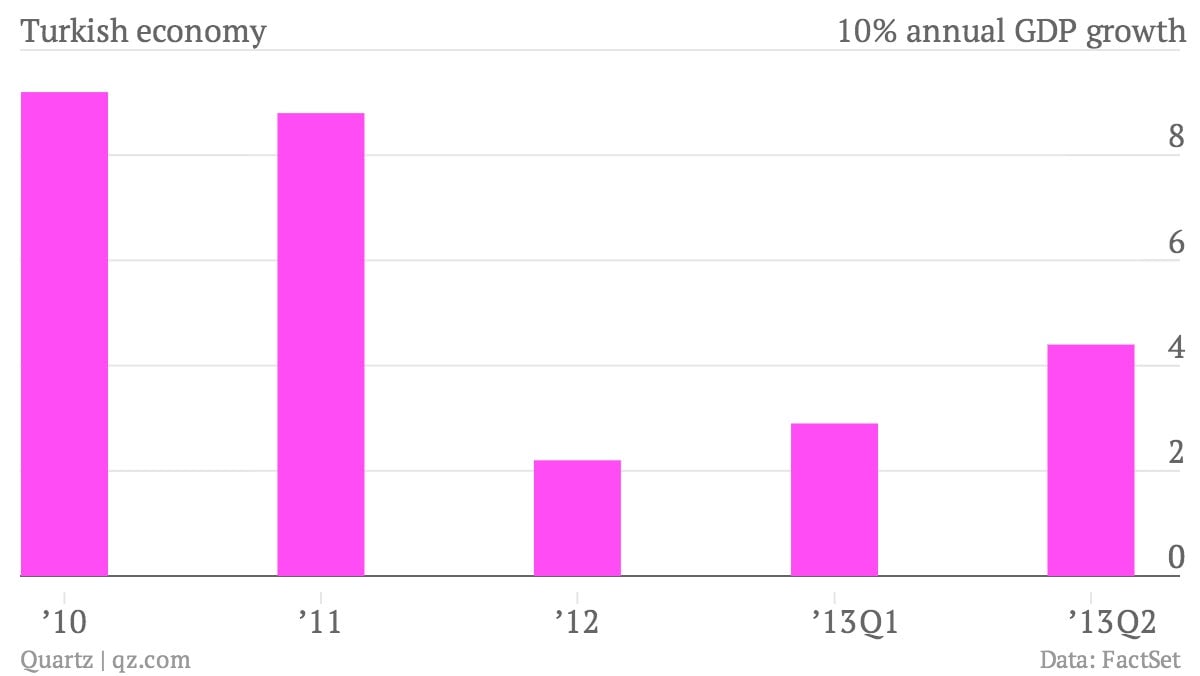

Crisis? What crisis? In the second quarter, the Turkish economy grew at a 4.4% annual rate, comfortably beating analysts’ estimates. This was double the rate of growth in 2012, as Turkey shrugged off the destabilizing effects of mass protests that gathered steam throughout June.

Crisis? What crisis? In the second quarter, the Turkish economy grew at a 4.4% annual rate, comfortably beating analysts’ estimates. This was double the rate of growth in 2012, as Turkey shrugged off the destabilizing effects of mass protests that gathered steam throughout June.

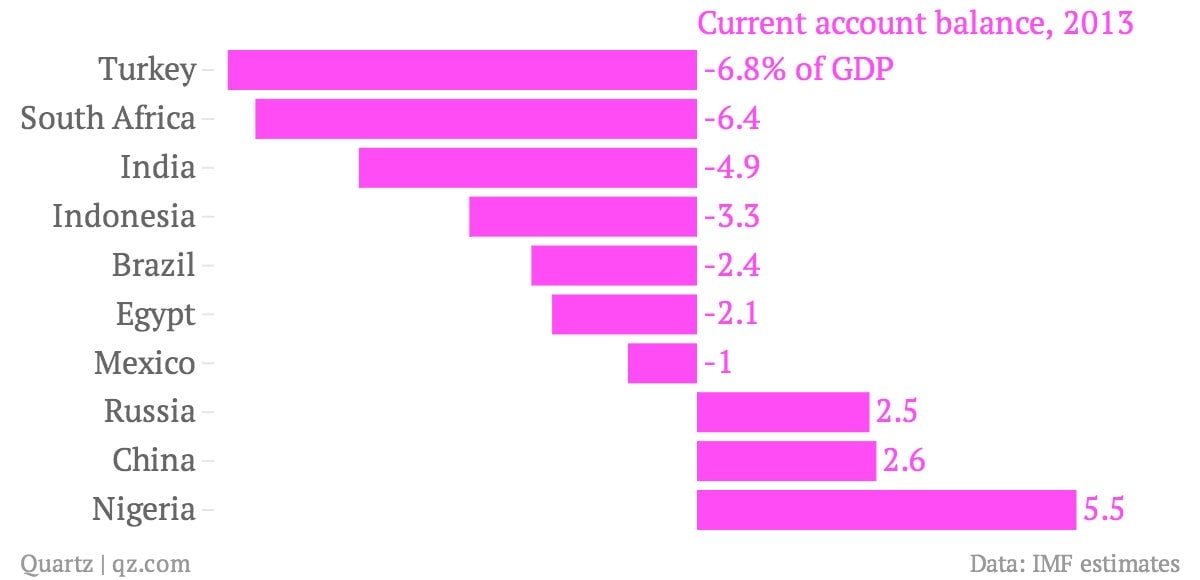

Despite this better-than-expected data, analysts are more likely to cut their forecasts for future Turkish growth than raise them. The strength of domestic demand, which propelled the second-quarter growth spurt, is also—somewhat paradoxically—a potential source of weakness in the future. This consumption is also fueling imports, with Turkey running one of the largest current account deficits among important emerging markets. (A country runs a current account deficit when the money it sends abroad to pay for goods, services and other investments exceeds the value of the financial flows it attracts via exports and purchases that foreigners make in the country.)

As investors have pulled money out of emerging markets in response to rising interest rates and the withdrawal of monetary stimulus in the developed world, the currencies of countries with large current account deficits have tanked. The Turkish lira has lost more than 10% against the dollar so far this year. Its 10-year bond yield has surged from 6.5% to just below 10%. Turkey’s benchmark stock index is down 8% for the year, versus an 18% gain in the MSCI World Index.

So far this year, Turkey’s taste for imports means that it needs to find around $5 billion per month to pay for its current account shortfall, which it does mostly via short-term borrowing instead of more durable foreign direct investment. When investors are happy to invest in Turkish securities, this is not a problem, but when options improve elsewhere the country’s ability to meet its various obligations comes into question. The resulting combination of higher borrowing costs, a weaker currency and rising inflation can dampen economic growth if not managed prudently.

The official response to the turmoil has been a bit of a muddle. Many believe that higher interest rates are needed to shore up the lira and rein in inflation, which is running at more than 8%. But the central bank’s unorthodox approach to policy, which involves tweaking a range of interest rates and adjusting various “corridors” for borrowing costs, more often than not sows confusion rather than provides clarity about its intentions.

A pledge by the central bank governor in late August to keep interest rates where they are—using unspecified tools other than the “rates weapon” to halt the lira’s slide—is the latest in a series of puzzling statements. This overcomplicated policy is also subject to heavy political interference; the economy minister declared himself “allergic to interest rates” in a recent television interview, while the prime minister blamed a shadowy “high-interest-rate lobby” for stoking the summer protests. On top of these policy challenges, ongoing unrest in neighboring Syria presents a large but unquantifiable threat to the Turkish economy.

The government recently cut its forecast for GDP growth to between 3% and 4% for this year and next. The balance of risks suggests that even these revised targets may turn out to be too optimistic.