The US Supreme Court’s funniest cases are the ones you never hear about

US Supreme Court justices have tough jobs. They’re charged with extremely grave duties, deciding matters of national import. Judging can be fun, however, and legal tales about serious disputes are often humorous and very rock ‘n’ roll—as illustrated by the recent matter of Peaches’ wild house party (pdf) in Washington, DC.

US Supreme Court justices have tough jobs. They’re charged with extremely grave duties, deciding matters of national import. Judging can be fun, however, and legal tales about serious disputes are often humorous and very rock ‘n’ roll—as illustrated by the recent matter of Peaches’ wild house party (pdf) in Washington, DC.

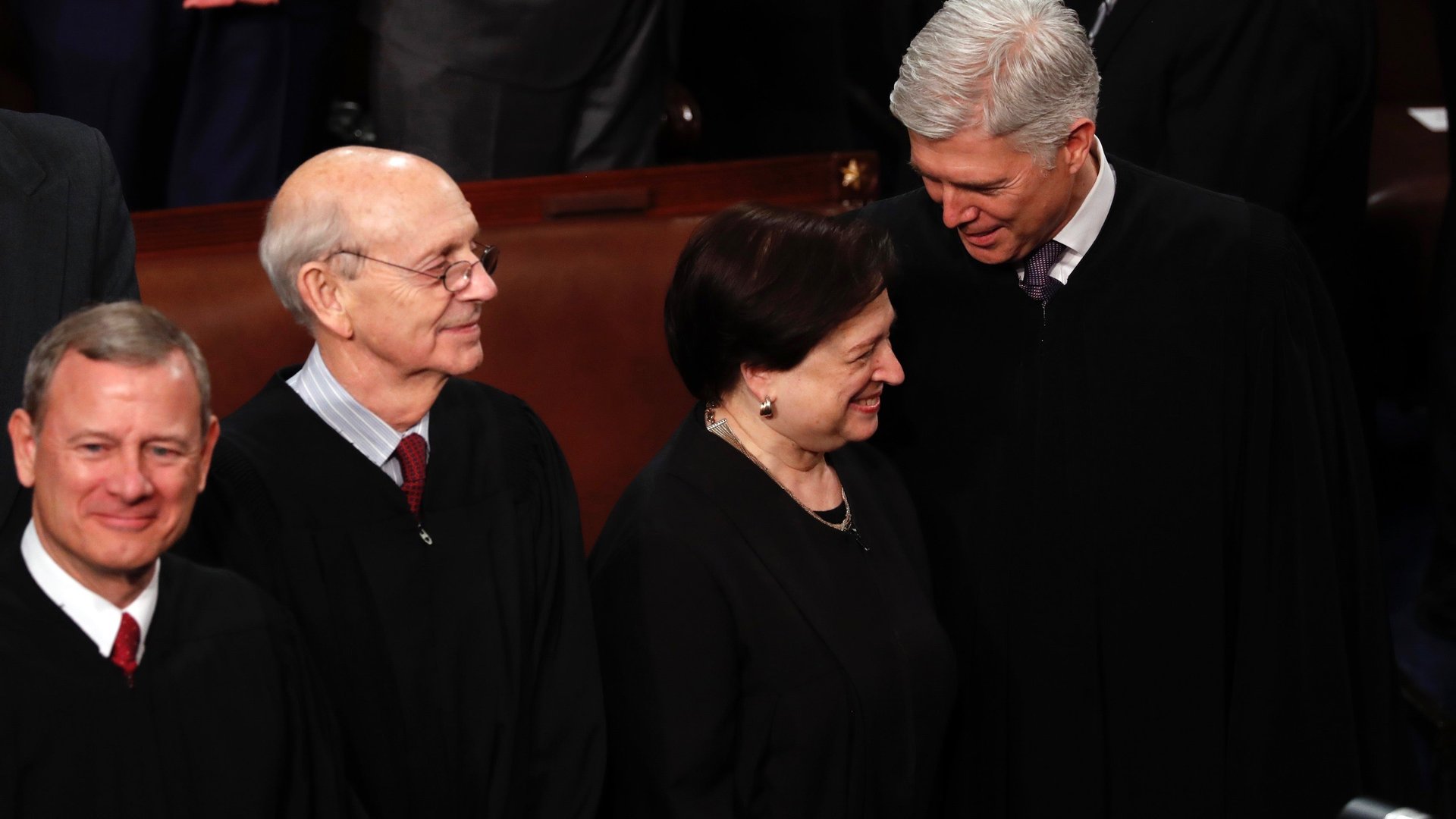

Peaches’ festivities yielded District of Columbia et al v. Theodore Wesby, a Jan. 22 case that demonstrates two little-known features of work on the high court. One, the judges have a side gig deciding DC judicial circuit court appeals because of a jurisdictional fluke. And two, their job can be a hoot, albeit highly intellectual and important.

The matter of Peaches’ guerrilla house party is a prime example of this. It’s a delightfully written opinion by justice Clarence Thomas, who is no partygoer and admits that his idea of a good time is hanging out in his RV with his wife at a Walmart parking lot.

The case also demonstrates the constitution in action, with its principles of law and rebellion protecting the people from unjust governmental intrusion. In the US legal system, the underdog can’t always win, but they sure can claim unconstitutional search and seizure and sue the cops for false arrest.

A night of revelry

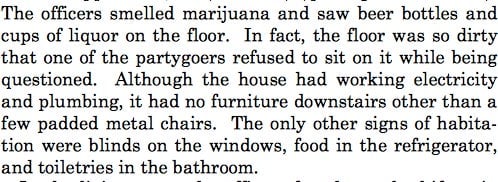

Here’s what happened. At 1 AM on March 16, 2008—almost a decade ago to the day—police got a call about a loud event at what previously seemed to be an unoccupied house in a DC neighborhood. The cops showed up and it turned out the home was very full and in disarray. There was no owner or host to authorize the entry, however, and police had no warrant to justify being inside the private property.

Regardless, the cops said they found a “raucous” and “debauched” affair that included drugs, an impromptu strip club, 21 guests scattered across a filthy floor, and no apparent host or homeowner. Only some of the alleged visitors claimed to even understand how they had come to be at what was maybe a bachelor party, maybe hosted by Peaches, who also went by the name of Tasty. The cops reached Peaches by cellphone, but she refused to return to the scene of the crime—or party.

The opinion is not intended to be funny. But it is a deliciously witty work, wryly conveying truth as strange as fiction. ”The officers found more debauchery upstairs,” explains Thomas. “A naked woman and several men were in the bedroom. A bare mattress—the only one in the house—was on the floor, along with some lit candles and multiple open condom wrappers. A used condom was on the windowsill…”

Police couldn’t get straight answers from the partygoers, many of whom tried to escape from the house but were arrested. Those who spoke to the cops made no sense and told inconsistent stories. Thomas writes:

Each of the partygoers claimed that someone had invited them to the house, but no one could say who. Two of the women working the party said that a woman named “Peaches” or “Tasty” was renting the house and had given them permission to be there.

One of the women explained that the previous owner had recently passed away, and Peaches had just started renting the house from the grandson who inherited it. But the house had no boxes or moving supplies. She did not know Peaches’ real name. And Peaches was not there.

According to Thomas, police then asked the woman to call Peaches, who answered her cellphone and explained that she had just left the party to go to the store. She wasn’t going to return just to get locked up. Rightly so: Her fellow revelers were indeed jailed.

Fighting law with law

After the criminal case, 16 defendants sued the DC police officers for false arrest, arguing that they had no warrant or probable cause to enter the property. Officers challenged the civil suit and the DC Circuit Court found against the cops, reasoning that there was no probable cause to arrest the revelers—as required by Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable governmental searches and seizures—because no one in the house could authorize the entry. Peaches wasn’t an owner, renter, or even present at the party and had no authority over the home, while the homeowner was also absent and unaware of festivities.

The police officers challenged that decision, arguing that they had probable cause based on the totality of suspicious circumstances. The high court agreed, opining:

Taken together, the condition of the house and the conduct of the partygoers allowed the officers to make several ‘common-sense conclusions about human behavior.’ Because most homeowners do not live in such conditions or permit such activities in their homes, the officers could infer that the partygoers knew the party was not authorized.

Justice Thomas further writes, “The officers also could infer that the partygoers knew that they were not supposed to be in the house because they scattered and hid when the officers arrived.” Their “vague and implausible answers to questioning” gave reason to infer revelers were lying, suggesting “a guilty mind.” He also notes Peaches’ evasions made the situation more suspicious.

The supremes all agree on this decision, at least in part. While the justices uniformly believe the officers are protected by qualified immunity and not subject to a civil suit, justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg see things differently from their colleagues.

They disagree with the majority’s reasoning on the Fourth Amendment. Sotomayor thinks the case can be reversed without even asking constitutional questions at the appellate level—appeals courts review lower court errors but are supposed to avoid deciding law, ironically.

Ginsburg, who is famously rebellious and is known by the hiphop moniker the Notorious RBG, rejects the arrests altogether. She doesn’t think the police had probable cause for it, at least not as the partiers were charged, explaining, “Ultimately, [revelers] were not booked for unlawful entry. Instead, they were charged at the police station with disorderly conduct.”

In Ginsburg’s view, though the officers should not be subject to a civil suit for their on-duty decisions, there was no disorderly conduct at Peaches’ party, and attendees didn’t necessarily know they couldn’t enter the home. So, she respectfully disagrees with her fellow supremes, concluding on behalf of the revelers and freedom, writing: “The Court’s jurisprudence, I am concerned, sets the balance too heavily in favor of police unaccountability to the detriment of Fourth Amendment protection.”