Swedish regulators want borrowers to pay off their mortgages faster. Like, in less than 140 years

Norway isn’t the only Nordic country worried about an overheated housing market. At a parliamentary hearing yesterday, Swedish officials sounded the alarm about rising household debt.

Norway isn’t the only Nordic country worried about an overheated housing market. At a parliamentary hearing yesterday, Swedish officials sounded the alarm about rising household debt.

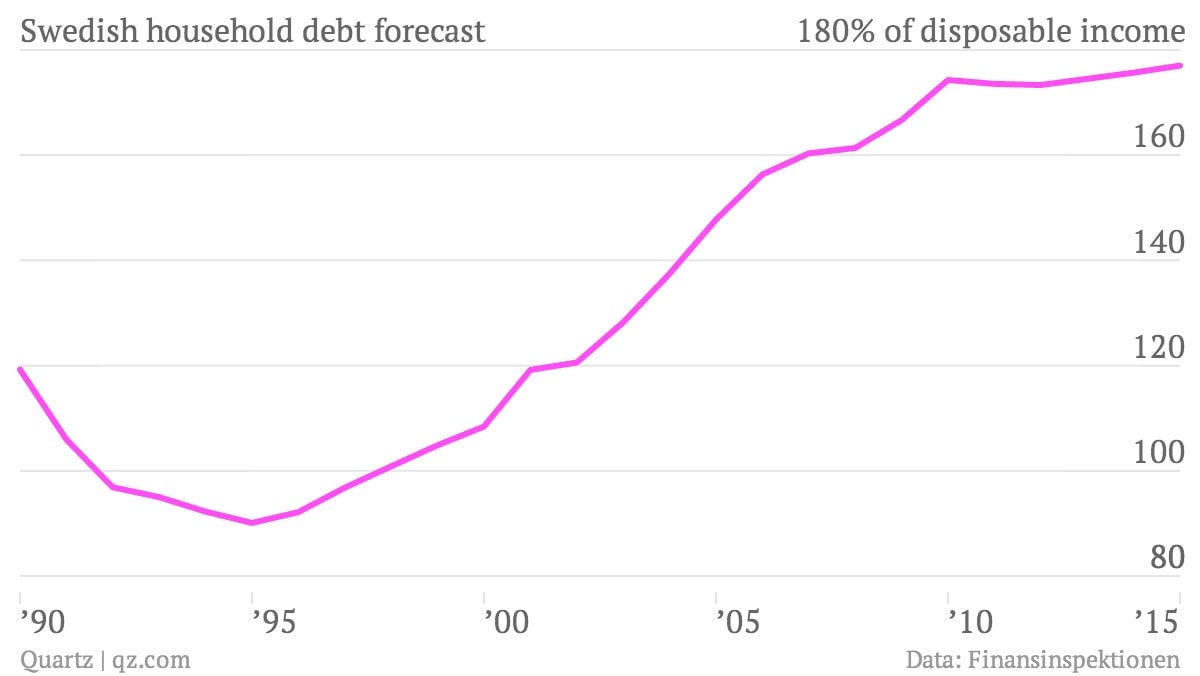

Swedes have one of the biggest household debt burdens in the developed world. The central bank thinks debt will rise to almost 180% of disposable income in the next few years. This is higher than the peaks that the US, UK, Spain and other countries reached before their credit bubbles burst.

But one reason for this high debt burden is Sweden’s idiosyncratic way of doing mortgages. Fixed-rate “bottom loans” cover up to 75% of a home’s value while a variable-rate “top loan” is added on if borrowers need more. But for the bottom loan, they don’t have to pay off the principal as long as they keep paying the interest. So, once the pricier top loan is paid off, many Swedes simply pay the minimum interest due on their remaining debt. Forever.

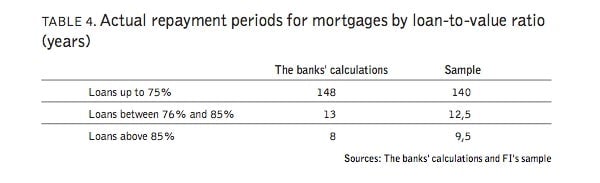

In a report released earlier this year, Sweden’s Financial Supervisory Authority (FSA) noted that at the current rate of repayment, it would take the average Swede more than 140 years (pdf) to pay off her mortgage. The table below, from the report, shows how long people are taking to pay off their loans in a sample inspected by the FSA and in calculations provided by banks.

But given the high debt burden and the fact that Swedish house prices, having fallen last year, are going up again—and have doubled since 2002—regulators are now proposing to stem this borrowing binge, by imposing mandatory repayment of a greater share of the principal on mortgages. In addition, the FSA and the central bank have been busy reining in mortgage lending, by lowering the amount banks can lend against the value of a house and raising the amount of capital banks must hold against mortgages as a buffer against potential losses.

Forcing borrowers to pay down more of their mortgage principal would mark a major change for Sweden. But if housing prices fall, that will hit people with big mortgage balances hard, and that’s clearly a problem on regulators’ minds. The theme of a two-day conference at the central bank that starts tomorrow is, simply, ”Bubbles”.