A visibly upset Donald Trump said Friday he would support a $1.3 trillion bill to fund the US government, hours after tweeting that he might veto it.

“There are a lot of things I’m unhappy about,” Trump told journalists in the White House’s Diplomatic Reception room at 1:30pm, during a press conference that he had announced on Twitter an hour before. “I will never sign another bill like this again,” he said.

Trump railed against the “ridiculous situation” that led to the bill, apparently referring to tense Congressional negotiations in recent days, and spoke bitterly of Democrats who demanded concessions to vote for it, calling their funding priorities a “wasted sum of money.”

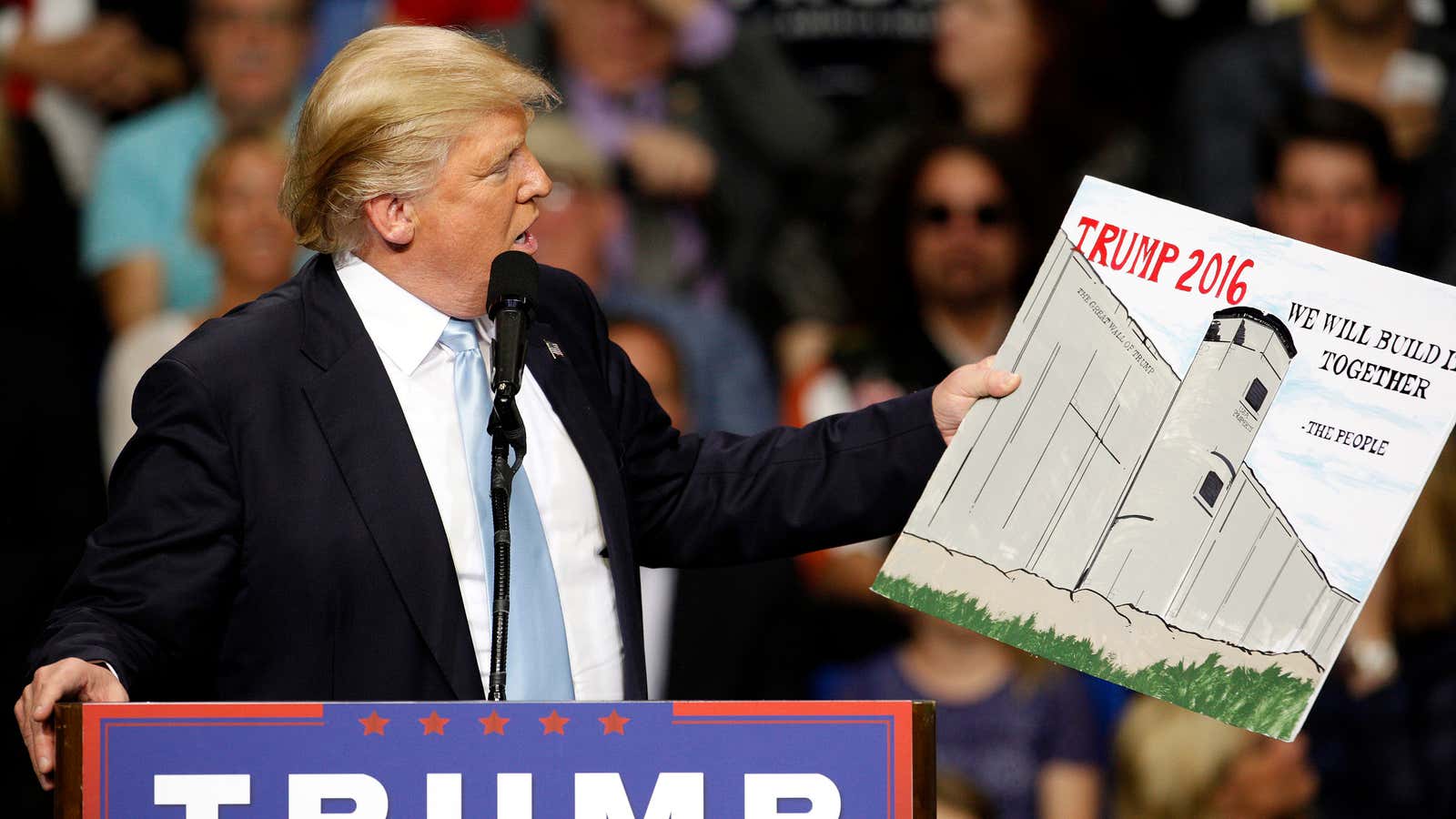

Trump’s reluctant support comes after a several tumultuous days of behind the scenes negotiations, say several people briefed on the situation. His last-minute threat to veto the bill reflects heavy pressure by the Department of Homeland Security to get more funding for the border wall—a wall that, depending on how Republicans do at the polls in November, may not get funded for years, or ever.

DHS secretary Kirstjen Nielsen met with Trump late Wednesday or early Thursday to try to convince him not to sign the bill, hours before it was voted on in the House yesterday, said one person briefed on the meeting. Any funding for the wall would go to the DHS’s budget, and the agency would oversee its construction. DHS never comments on conversations it has with the president, a spokesman said when asked about the meeting.

The current spending bill grants DHS $1.6 billion for Trump’s much-discussed border wall, an amount that will allow the administration to build just 33 miles of new wall, while reinforcing other areas. That’s far less than the original $25 billion sought by the White House in this bill to fund the wall for three years, a senior Congressional source said. That figure was suggested by the White House in exchange for a three-year extension of the “DACA” program that allows nearly one million immigrants brought to the US as children to stay and work in the country.

Democrats countered that they wanted citizenship for 1.8 million people, a permanent solution, and both sides came to a standoff, again, mirroring the back-and-forth that has happened since Trump suspended the program last September. The spending bill passed the House Thursday afternoon and the Senate early Friday morning without either long-term wall funding or a DACA solution.

Later Friday morning, however, Trump surprised Democrats, Republicans, and some officials in the DHS when he threatened to veto the bill altogether on Twitter, citing the border wall and DACA negotiations. Several Congressional aides working on the bill said less than an hour before Trump’s press conference they had no idea whether he was going to sign it or not.

Failing to sign a bill that both houses of Congress had already passed, and that the administration’s budget director said the White House supported, would have been an unprecedented move for a US president. It would also have automatically triggered a US government shutdown—the House is no longer in session ahead of a two-week spring break, and the Senate’s last day before the break is today. Many members of the House have already returned to their constituencies.

Trump met with defense secretary James Mattis less than two hours before the press conference. He highlighted defense funding when he spoke, a signal that Mattis may have convinced him of the merits of signing the spending bill. “We had no choice but to fund our military,” Trump said by way of explanation. “We have to have by far the strongest military in the world.”

Trump also demanded today that Congress give him a “line item veto” on future spending bills, and that the Senate get rid of its “filibuster rule” which requires 60 votes in order to pass legislation. Both are unlikely—Senate Republicans are unwilling to change the filibuster, because they’re inevitably likely to lose the majority at some point in the future. US presidents have long coveted the ability to veto parts of budgets they don’t like, but the Supreme Court ruled in 1998 that such authority was unconstitutional.

This could be the last time that the White House and the DHS will have a chance to influence a Congressional budget before the 2018 midterm elections. (The bill funds the US government through the end of September, and Congress is likely to adopt stop-gap funding until after the elections.) After November, Republicans, who have lost some high-profile special elections in recent weeks, might lose their majority—and their sway—in the House.