The expulsion of African migrants from Israel has been delayed yet again—this time until the end of the Jewish Passover festival.

The Israeli government, pressed to justify the deportations, asked the Supreme Court for an extension to submit classified documents as part of its filings, which are expected to shed more light on the African nation to which the migrants are being sent. The court agreed to extend the deadline from the original Mar. 26 deadline to Apr. 9, a timeline that falls in between the weeklong Passover celebration marking the freedom of Israelites and their liberation from Egyptian slavery.

In a remarkable change of heart, the state also said it will likely grant refugee status to Sudanese migrants from Nuba and Darfur areas. Only 10 Eritreans and one Sudanese out of over 35,000 migrants have been recognized as refugees in Israel since 2009, according to the United Nations.

In early January, the government said it would purchase tickets, obtain travel documents, and give each migrant $3,500 to leave—threatening them with arrest if they are caught still in the country after the end of March. That policy decision culminated in years of violence, harassment, and arrests that Africans have faced in Israel, with state officials calling them “infiltrators,” a “cancer” to society, and economic migrants in search of opportunities. In mid-March, officials also closed the Holot detention facility in the Negev desert, where more than 10,000 people were once held, as a sign that it was serious about kicking out Africans.

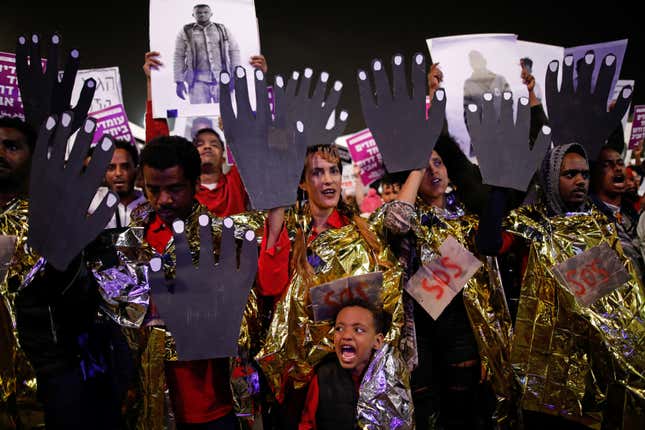

The expulsion has so far drawn protests and criticism from the United Nations, human rights agencies, academics—and even ardent supporters of the Israeli government, who warned prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu of “incalculable damage” to Israel’s reputation. This week, amid the legal wrangling, as many as 25,000 people demonstrated in Tel Aviv in support of the asylum seekers.

The violence directed at African migrants is discordant with the story of Israel and its formation: a nation built by migrants, many of whom escaped Nazi persecution, and who have divergent ancestral lands in Europe (Ashkenazi Jews), the Middle East and North Africa (Mizrahi Jews), besides Africa (there are about 140,000 Ethiopian Beta Jews living in Israel). The deportations are also jarring given how much Jerusalem is increasingly building alliances with African nations in order to do business and win geopolitical battles.

As Israeli-Canadian journalist David Sheen recently wrote, the violence and racism meted out against African migrants “teach us that while the greatest danger posed to African refugees in Israel is the plan to deport them back to statelessness and suffering, they also face other grave dangers, even if they are eventually allowed to remain in the country.”