China is funding a $90 million South Pacific wharf big enough for warships

China is flexing its maritime muscle. In the South China Sea last week, it put on its biggest-ever display of naval power, and its navy is conducting a live-fire drill in the Taiwan Strait this week, rattling nerves in Taipei and beyond.

China is flexing its maritime muscle. In the South China Sea last week, it put on its biggest-ever display of naval power, and its navy is conducting a live-fire drill in the Taiwan Strait this week, rattling nerves in Taipei and beyond.

Amid such exercises, defense analysts are wondering what Beijing has in mind for a $90 million wharf project—built with a loan from China—in the South Pacific nation of Vanuatu. So are some lawmakers in Vanuatu.

The project’s loan terms were not made available for Vanuatu’s parliament to assess, opposition leader Ishmael Kalsakau recently noted to Fairfax Media. Lawmakers couldn’t see whether the terms included a debt-equity swap that would let China take over the facility if Vanuatu defaulted—a fact Kalsakau found ”extraordinary.” A default seems entirely possible, with the wharf, opened last year, not attracting enough business from cruise lines and cargo vessels to justify the money that went into it.

China’s hope is that “the debt of the Vanuatu government will be so onerous that they can’t pay it back,” Malcolm Davis, a defense expert at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, told Fairfax. “The Chinese will say, ‘The facility is ours for 99 years,’ and the next thing you’ve got a [Chinese destroyer] docking there.”

“Clearly,” he added, “the Chinese are serious about establishing a military base in the Pacific.”

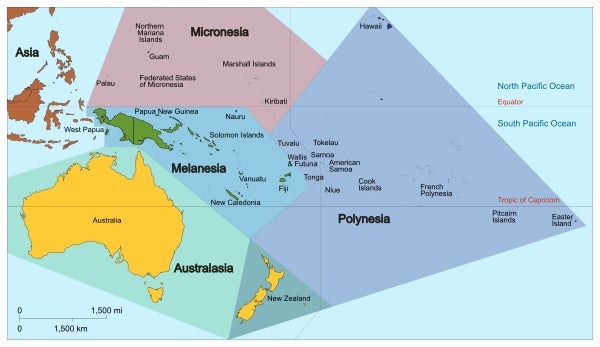

If it does, that would have major security ramifications for the US and its partners, weakening the advantage America gains from its military bases in Guam. Among Pacific island nations, Vanuatu, Samoa, and Papua New Guinea have all become heavily indebted to China. Many politicians in these countries defend the use of Chinese funding to build much-needed infrastructure. And financing comes from other nations, as well, of course: A port funded by Japan recently opened in Vanuatu (pdf).

Both Vanuatu and China have denied recent reports that Beijing plans to establish a military base in the island nation. But Vanuatu’s strategic value is hard to deny. During World War II it was overrun with US troops trying to stop Japan’s expansion. The town of Luganville, where the wharf project is located, hosted one of the largest military bases in the Pacific theater.

China has been accused of debt-trap diplomacy, whereby it showers weaker nations with development funding—often for expensive projects of dubious merit—with an eye toward later using their strategic locations or resources. In December, Sri Lanka, with more than $1 billion in debt to China, handed over a port on a 99-year lease to companies controlled by the Chinese government.

Meanwhile China has proven itself adept at playing the long game. In the mid-1990s its facilities at Mischief Reef in the South China Sea started off as a “fishermen’s shelter,” or so Beijing reassured the region. Today it sports an airfield, hangars, radars, jamming equipment, and air-defense weapons, all quite near the Philippines.

If China does take control of the wharf at Luganville, Beijing is sure to offer reassurances of its peaceful intentions. Time, it knows, is on its side.