Russia’s greatest Ponzi mastermind is dead, but his legacy lives on in the crypto world

Sergei Mavrodi, creator of one of the largest Ponzi schemes in history, died last month at age 62, potentially leaving millions of “investors” in countries around the world in the lurch. Beginning around the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Moscow-born Mavrodi’s exploits expanded and evolved over the course of nearly 30 years, putting him in the same league as Bernie Madoff, who operated arguably the biggest such fraud ever, and Charles Ponzi himself, the Italian con artist whose name is now synonymous with this type of financial deception.

Sergei Mavrodi, creator of one of the largest Ponzi schemes in history, died last month at age 62, potentially leaving millions of “investors” in countries around the world in the lurch. Beginning around the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Moscow-born Mavrodi’s exploits expanded and evolved over the course of nearly 30 years, putting him in the same league as Bernie Madoff, who operated arguably the biggest such fraud ever, and Charles Ponzi himself, the Italian con artist whose name is now synonymous with this type of financial deception.

But Mavrodi was different. He kept his public standing and continued to expand his financial empire even after its true nature was exposed. Most recently, Mavrodi’s scheme has evolved to capitalize on the infatuation with cryptocurrencies, raising questions about what is and is not a legitimate investment, and our motivations to invest in the first place.

While several of the websites associated with Mavrodi’s “investment vehicles” now display messages announcing their “ultimate and irreversible” closure due to Mavrodi’s death, there are others inviting investors to participate in Mavrodi-inspired cryptocurrency offerings, supposedly fulfilling the Russian’s “last wish of beating Bitcoin” with his own crypto token. In Mavrodi’s world, it is nearly impossible to know when one scheme ends and another one begins—and equally impossible to imagine that it is really all over given his notoriously persistent track record.

Mavrodi’s enterprise is called MMM, which is an acronym for “we can do a lot” in Russian. In its first incarnation in the early 1990s, as many as 10 million Russians participated in it as the country transitioned to a market economy. At the time, MMM was supposedly so busy with customers that employees didn’t have enough time to count all the cash flowing in, resorting to measuring it by the roomful. MMM even created its own paper currency at the time, which later evolved into a digital version that is considerably easier to launder. Contacts at MMM either declined to comment on this story or didn’t respond to queries.

Risks and rewards

To understand why someone would put their money in something like MMM, and why the fraud is so persistent and timeless in nature, you can start by speaking to an early 1990s “investor” like Alexey Khodorych. The pale, 40-something middle manager of a Russian children’s book publisher still enjoys talking about the time he “tricked the people who were trying to trick him.” MMM promised a 1,000% annual return, and some people were endorsing it as an extraordinary way to make money quickly. Others said it was an obvious scam—a Ponzi scheme to be precise.

Khodorych first heard about MMM in September 1994. Only a month earlier, the organization had been closed temporarily following government accusations of tax evasion, raising concerns over its legitimacy. But Khodorych wasn’t sure if the rumors that it was a scam were true. Like most Russians at the time, Khodorych had no clear idea of what a legitimate investment should look like. In the communist USSR there was no such thing as a personal investment. But MMM was open again and taking investors. Khodorych thought if he got in early enough and got out quickly, he’d still be able to make some good money.

“I invested somewhere between $3,000-4,000 and doubled it,” Khodorych said via Skype in 2015. This was a tiny fortune at the time. “I bragged about it,” he says. “But I told everyone that what I did was too risky and that they shouldn’t do the same.”

Winners, like Khodorych, are the exception. There were so many losers that when the initial MMM closure took place in July 1994, the Russian government found itself in a delicate situation. Thousands of people who were already relatively poor had lost everything. Estimates of the losses vary widely, ranging anywhere from $100 million to upwards of a billion dollars.

If this story sounds like a one off—the kind of thing that only happens at the fringe when an economy is emerging from collapse, or that the world learns from and doesn’t repeat—well, that notion is mistaken. Over the years, MMM continued to flourish, popping up periodically in Russia before spreading to Latin America, Africa, and Asia with websites in English, Hindi, Indonesian, Spanish, and Mandarin, among others.

The MMM global website boasts, albeit with little formal substantiation, that there are 250 million participants in 118 countries. Up until very recently, the MMM Mexico site greeted visitors with a live chat and the contact info for two consultants who could help investors set up a cryptocurrency wallet. The MMM India website offered customer testimonials, detailed instructions on how to buy and sell bitcoin, and all the trappings of a legitimate financial enterprise.

What began as a relatively simple operation affecting people in a single country has stretched across the globe, using an online platform to capture the savings of millions. While some regulators wanted to shut it down, others didn’t know if they had the authority to do so because of the clever, ever-evolving structure of the scheme. Now, it is unclear what parts of the operation are still active or not, posing yet another challenge to regulators.

Andrei Nechaev is deeply familiar with the regulators’ struggle. He was Russia’s economics minister in the early 1990s and dealt with the aftermath of MMM’s first failure. “MMM used different tools so as not to be breaking any laws,” he said in his raspy smoker’s voice in Moscow in 2015. “The government was right to finally stop it, but it took too long.”

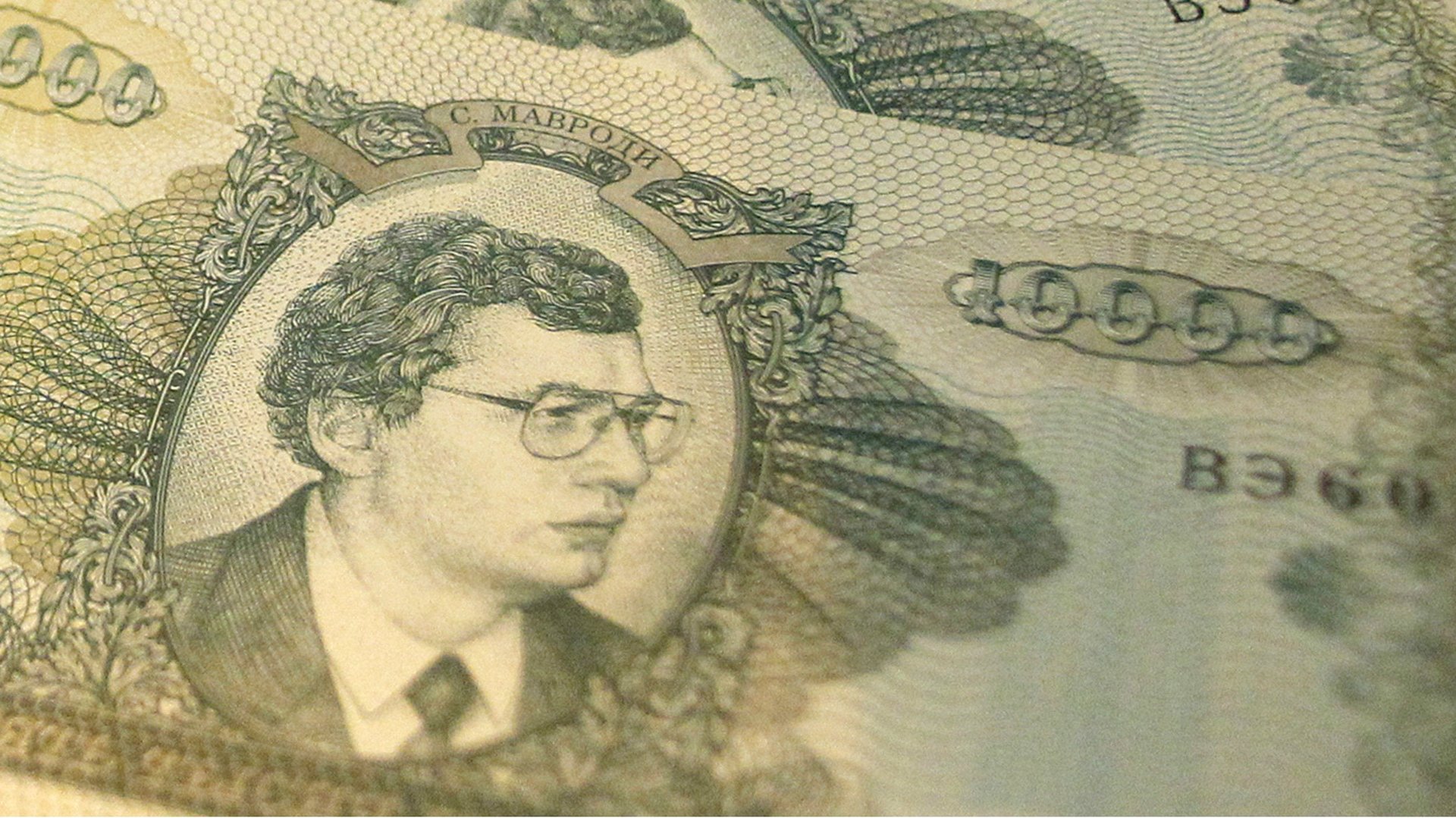

Beginning in 1992, MMM offices were set up around Moscow and other Russian cities, where investors could buy “Mavros.” Named after the organization’s founder, Mavros functioned as shares in MMM. They were printed in different denominations with a variety of colors, including American-dollar green. (In fact, Mavrodi claimed he originally considered turning US dollars into Mavros by painting them red, but later abandoned the idea.) Mavros looked like an authentic currency issued by a legitimate government, embossed with the triple-“M” logo and a portrait of Mavrodi. Investors could buy these bills at MMM offices and later sell them back to MMM, hopefully for a profit. Nechaev says there were many MMM offices where people could buy Mavros, but few where they could be sold back.

The surest sign of a crash was when long lines stretched around the MMM offices. Sadly, this troubling signal may not have been immediately obvious to Russians who had lived in the Soviet Union and were accustomed to long queues.

“Russia’s financial regulation was very underdeveloped back then,” Nechaev said. “There weren’t technically any laws prohibiting Ponzi schemes. And MMM would find a way around the laws that did exist.” For instance, Nechaev noted that the organization dodged rules that would normally apply to entities offering shares, by claiming that the Mavros were simply paper. Not surprisingly, there were no special rules for buying and selling paper. The government stopped MMM, at least temporarily, by charging the scheme’s founder, Mavrodi, with tax evasion.

With his greasy hair, thick glasses, and Adidas track suit, Mavrodi didn’t look like a celebrity salesman or mastermind. Yet he’s well known to most Russians.

The adventures of Lenia Golupkov

Mavrodi claimed to have been born in 1955 in Moscow, the son of a laborer and an economist. He studied at the Department of Applied Mathematics at the Moscow Institute of Electronic Engineering. After graduating in 1978, by some accounts, Mavrodi went on to work as a software engineer before launching his own business trading audio and video recordings. According to others, Mavrodi worked as a night watchman. Not much is known about his background, but nothing that surfaces would suggest his unusual aptitude for tapping into peoples’ vulnerable impulses.

The first thing most Russians recall at the mention of Mavrodi is the commercials. MMM spots were among the most frequently broadcast advertisements on Russian television in the early 1990s, appearing more than 2,500 times from March to May 1994, according to Ellen Mickiewicz’s book Changing Channels: Television and the Struggle for Power in Russia. They were more like a mini-series than an advertisement: Each commercial featured the unfolding life of a fictional, simple-minded character named Lenia Golupkov.

In the first episode, Golupkov appears dopey and nervous as he removes his black fur cap and scratches his head while purchasing his first Mavros. In the next commercial, Golupkov returns to the same office, Mavros in hand, smiling like a kid at Christmas, as the receptionist counts out his pile of rubles. In a subsequent episode, the camera zooms in on black leather riding boots that Golupkov bought for his wife with his winnings. Then the camera zooms out to reveal Golupkov’s wife, gazing admiringly at her husband. In another episode Golupkov has bought his wife a fur coat, the symbol of conventional desire of Russian women. A chart shows Golupkov’s past and future purchases: boots, a fur coat, a house, and a car. Thanks to MMM, things are looking up for this average Russian guy.

It’s difficult now to imagine how such simple images—a new pair of boots, a fur coat, or a car—could inspire millions to invest money they couldn’t afford to lose in something they didn’t understand. But MMM didn’t seem all that implausible to the average Russian. A number of people were growing fabulously wealthy as Russia privatized its state-owned assets. Most observers probably couldn’t comprehend how a modest investor could become a billionaire seemingly overnight, as some of Russia’s oligarchs did. And if Lenia Golupkov could make it big, then perhaps anyone could.

Being on TV at all was just as important as the MMM commercials’ storyline. In Russia, people tended to trust what they saw. The moving image carried the authority that the internet does today, and so too did MMM’s commercials.

There’s speculation as to how Mavrodi got the money to run these ads and create a network of MMM offices throughout the country at a time when most citizens had very little. Many Russians believe government officials had a hand in supporting Mavrodi—an idea that’s not entirely far-fetched, but one without hard evidence.

Rise of the oligarchs

Mavrodi had his own way of explaining how MMM got started. “In 1994, privatization began. Scoundrels and rogues without honor and conscience, the current oligarchs, during these changes were to take public property, the works of millions of generations,” Mavrodi explained to us via an e-mail exchange. “The population did not understand anything that was going on. I understood everything perfectly, and therefore decided to intervene. I bought stocks in governmental projects through auctions held at the time—stocks in the most profitable and promising industrial enterprises and financial institutions—and gave them out to the people. I created MMM to accumulate the necessary funds.”

At least one part of Mavrodi’s story is easy to corroborate—Russia’s privatization did begin in the 1990s and immense fortunes were up for grabs. One of the main challenges the government faced was distributing the wealth of the country’s state-owned companies. It tried to do so through voucher privatization. Every Russian family was sent vouchers that could be used to purchase ownership in formerly state-owned enterprises. But in the end, only the most aggressive Russians stood a chance of winning.

“The Russian people had no idea what to do with the vouchers when they received them for free from the state and, in most cases, they were happy to trade them for a $7 bottle of vodka or a few slabs of pork,” according to Bill Browder, in his memoir Red Notice. He was one of the first foreigners to make his fortune in post-Soviet Russia.

“A few enterprising individuals would buy up blocks of vouchers in small villages and sell them for $12 each to a consolidator in larger towns,” he wrote. Then another larger consolidator would take them and another and eventually they would wind up in Moscow where men like Browder and other up-and-coming oligarchs would buy the stakes in bundles, gaining control over vast portions of the Russian economy.

Mavrodi claimed he was a mitigating force during this period, but in reality he exploited the confusion by offering his own sort of voucher, not unlike his efforts to exploit confusion around crypto today.

In late 1994, Mavrodi was arrested for tax evasion in connection with MMM and sent to jail for 70 days. Ever resourceful, he profited from the arrest by tapping into Russians’ distrust of their government. Mavrodi said the tax evasion charges were evidence that the Russian government was behind MMM’s downfall. “The system did not collapse at all,” he said. Rather, “it was artificially destroyed at the peak of its development” by a government greedy for tax money.

MMM participants loyal to Mavrodi took to the streets to show support. Men and women gathered in front of the Interior Ministry building in Moscow yelling pro-Mavrodi slogans: “Free Mavrodi!” and “Mavrodi for Parliament!”

In fact, Mavrodi ran for the Duma, Russian’s version of a parliament, as soon as he was released from prison in October 1994. His campaign pitch to the Russian people was that they should elect him because this was the only way he would have immunity, stay out of jail, and get MMM investors their money back. It worked. Less than a month after his release from prison, Mavrodi was elected to parliament.

But Mavrodi did not attend Duma meetings during the years that followed. It’s also unclear whether he repaid any investors during his time in parliament. He was stripped of his office in January 1996 due to absenteeism, and the tax evasion investigation restarted.

Mavrodi went into hiding for the next several years. The authorities found him in early 2003 and arrested him in the humble apartment where he lived in central Moscow. For the next four years, Mavrodi sat in jail awaiting trial. During that time, he wrote several colorfully titled books including, Letters to the Wife, where he details his day-to-day life behind bars in letters to his spouse, a former Russian fashion model. In 2007, Mavrodi was tried and found guilty on charges of tax evasion. He was sentenced to more than four years in jail and fined 10,000 rubles, or approximately $390.

On his final day in court, Mavrodi appeared in his usual Adidas tracksuit. Many supposed Mavrodi sympathizers were in attendance, including Marina Bolotova, a 71-year-old MMM investor who lost the money she’d saved for her own funeral in the scam. Nonetheless, Bolotova told reporters, “Let [Mavrodi] go, he didn’t kill anyone. They should put in jail those who caused this chaos.”

Mavrodi was released a month after he was convicted, due to time served while awaiting trial in May 2007. It wasn’t long before he was devising his newest venture—MMM-2011.

Going global

Functionally, MMM-2011 was no different from Mavrodi’s original scheme—the funds of incoming participants were used to pay prior participants. There were no real investments or opportunities to genuinely increase the overall size of MMM-2011’s holdings other than the addition of new participants. But there were several new quirks that set MMM-2011 apart from its predecessor, and this scheme went global.

MMM-2011 operated almost entirely online, which suggests Mavrodi was trying to attract a younger generation of internet users. People could sign into the website and create accounts where they stored money that they then voluntarily transferred to other participants. They could also request deposits into their account from other people. The website was eventually updated to accept bitcoin payments and recommended using it instead of fiat currency.

Unlike the first scheme, which was marketed as a legitimate investment in real business interests, MMM-2011 was open about the fact that there were no investments. Indeed, Mavrodi seemed to relish disclosing the risks inherent in MMM’s operations. When potential MMM participants create an account on MMM Global’s website, they are still pointed to a warning:

There are no guarantees and promises! Neither explicit nor implicit.There are neither investments nor business! Participants help each other, sending each other money directly and without intermediaries. That’s all! There’s nothing more.

There are no securities transactions, no relationship with the professional participants of the securities market; you do not acquire any securities. (Do you need them? :-))

There are no rules. In principle! The only rule is no rules. At all! Even if you follow all of the instructions, you still may “lose”. “Win” might not be paid. Without any reasons or explanations.

And in general, you can lose all your money. Always remember about this and participate only with spare money. Or do not participate at all! Amen. :-))

After reading this message, it’s hard to believe anyone would want to invest in MMM. Yet this is where Mavrodi’s appeal to people’s aspirations, not only in Russia but in other beleaguered economies, comes in. He described a world divided between the haves and have-nots. Then, addressing the have-nots, he convinced them to join a “community of ordinary people selflessly helping each other.” According to Mavrodi, MMM is a “mutual aid” system where members donate money “peer-to-peer.” In doing so, he argued, participants are subverting the global financial system and even accelerating its demise. Mavrodi appealed to his own brand of liberation theology.

When you watch a MMM video available on all the global sites, it’s easy to see the ideology’s somewhat skewed appeal. The video’s narrator, in a stilted American accent, describes the world as an “inhumane and unjust” place. “It is a world of money,” says the narrator, “it is not for the people.” Contrasting images flash across the screen: starving children and beggars against well-clad women shopping; yachts, mansions, and luxury cars set against slums. In this world, there are two categories—bankers and workers.

The video informs these workers that they have spent their whole lives “working for some oligarch” and in return they will receive nothing more than a “small pension,” will be “half-starved [by] old age,” and when they die they’ll be “thrown in the dust bin.” They are encouraged not to give their money to the banks and exploitive bankers, but to MMM where it will help others in need. “Love thy neighbor,” the narrator urges: Participating in MMM will give you “the feeling that you are not alone. You will always be helped in tough times.”

Mavrodi described himself as an “air traffic controller, connecting people with each other,” in an email. “There are just millions of members, ordinary people who send each other money,” he wrote. They’re “transferring money without any guarantees or promises. Essentially, you are just gifting money to a stranger without asking anything in return.”

In this incarnation, MMM presented itself as a charity with all of the advantages of an investment. It offered a set of tools to calculate expected returns, for example, similar to what an investor might use when estimating the returns on a government or corporate bond.

On the MMM India website, where the tool is still available and functioning, users enter the amount of their initial deposit and view the projected value of their account balance over the next year using something called the “calculator of happiness.” A pop-up box asks “How much money do you need to be absolutely happy?” and “How long are you ready to wait?” If you decide you need 10,000 rupees (about $150) for full happiness 10 months from now, you simply need to invest 726 rupees today, at a 30% rate, according to the happiness calculator. Accordingly, in 10 months, you are supposed to have 10,000 rupees comfortably sitting in your pocket.

However, even before the closure announcements following Mavrodi’s death, MMM frequently went into “pause mode.” During these times, no one could request aid, or more precisely get paid back from MMM. But people were still free to buy Mavros, and were heartily encouraged by MMM’s social media postings to do so. After we inquired about opening an account several years ago, one local recruiter in Moscow helpfully pointed out that there were often pauses around the holidays.

Does that sound like a good place for savings? Mavrodi finished his description of the system with this assurance: “That’s all. Nothing tricky.”

“I’m not very risk averse”

You might think the average MMM participant is poor and uneducated, but it’s easy to find people who do not fit this profile. Take Pavel Borisevich. In his early 20s, Pavel worked for a prominent businessman, and he was about to finish his psychology degree at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow when we met with him in 2015.

He found out about MMM through a friend at his university who claimed to have recruited 100,000 participants. Borisevich’s interest in MMM grew when he came into family money: It was tradition in his family that when a child turned 18 they received a small sum of money, and the family watched how she or he handled it. Borisevich got 40,000 rubles ($700). After dabbling in stocks and bonds, which he said gave him returns of “only” 10% per month, he decided to take half of his money and invest it with his friend in MMM in hopes of earning more than 75% monthly.

Before making the investment, Borisevich told his father about his plans to put money in MMM. His father recalled what had happened in the 1990s when the scheme imploded, but he simply advised his son that MMM was a “real thing” and “you can earn money if you get out quick enough.” Borisevich put his first 20,000 rubles in and a month later walked away with 60,000—even more than he had hoped for.

Borisevich immediately put the 60,000 rubles back into MMM. “I’m not very risk averse,” he said with a laugh. A month later, he had 110,000 rubles. Participating in MMM began to look so attractive that Borisevich’s father wanted to invest. Borisevich’s friend informed him that given the current participation rates, he expected that MMM would continue to prosper. With that reassurance, Borisevich helped his father invest 210,000 rubles in MMM.

You probably guessed where this is going: MMM crashed and Borisevich’s father lost his money. Luckily, his friend was able to use his connections with MMM to get back 185,000 rubles of the original investment. Borisevich’s father was luckier than most, though he didn’t necessarily see it that way. “To say my father was upset is an understatement,” Borisevich said.

Borisevich knew exactly what he was getting into from the start. He explained matter-of-factly that “MMM-2011 is different from the earlier scheme because Mavrodi says that it’s a pyramid. He probably set it up online because there are no papers. No legal trail.” This sort of suspicious behavior doesn’t bother Borisevich at all. In fact, he had read several of the books that Mavrodi wrote while in jail and admired him. “He says whatever he wants and his style is cool—relaxed. He makes these YouTube videos wearing jeans and a t-shirt and leaning back in a chair,” Borisevich said, kicking back in his chair, Mavrodi-style, with his arms folded behind his head. “It’s clear that Mavrodi doesn’t have any fear,” Borisevich said.

If someone as well educated and knowledgeable in MMM’s history as Borisevich was willing to invest, it’s not surprising that people without his relatively privileged background could be persuaded. In smaller towns outside of Moscow, the organization invited pensioners to attend information sessions in return for free groceries. In India, MMM hosted friendly cricket matches—played against local police teams—and distributed food in hospitals. This type of publicity may seem just as sound to some people as audited financial documents would to others.

Mavrodi’s genius puzzled government officials around the world. MMM’s latest incarnation clearly disclosed its risks and was therefore not fraudulent, at least not in the typical sense. MMM was not necessarily lying to its customers. But as Nechaev, Russia’s former economics minister, pointed out, “if I tell you that I’m going to steal from you right before I do it, that doesn’t make it legal.”

Mavrodi’s response was that “the system does not break any laws. We do not fall under the category of a pyramid. In any country!” MMM was a voluntary transfer of money between willing persons. Depicted this way, what right does a regulator have to dictate to whom someone can or cannot give money? If regulators forbid voluntary money transfers between people, Mavordi argued, countries would be forced to forbid “all private institutions.” He said in an e-mail that he ought to be able to spend the money as he chooses: “Maybe I want to burn money? I have the right.”

Falling through the cracks

If Mavrodi was committing crimes, it’s difficult to tell exactly which agency would be responsible for stopping him. In Russia, some say the central bank or the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Others say the Federal Securities Board. The Consumer Protection Service said it was a financial matter and therefore outside of their jurisdiction. The Federal Antimonopoly Service determined that MMM was a financial pyramid and the Prosecutor General subsequently opened a criminal case in July 2012 though, even years later, circa 2015, the site was still active and accepting investors. MMM Russia appears to have since been shut down.

In some countries where MMM took root, the watchdog institutions are weak and there’s confusion among the public as to which authority is in charge. Take for example this consumer complaint on the website of India’s Council For Fair Business Practices:

Hello Sir,

MMM India Company is now doing money circulation business in Odisha and cheating people. I request you to take steps to investigate and save our people of Odisha.

Thank You.

And the reply from the Redressal Council:

The complaint is not under our purview, you may approach Press/Media with the complaint.

In Indonesia, the Financial Service Authority (OJK) had done little besides issuing a warning reminding investors that “not all financial institutions are registered with the OJK” and “thirty percent reward per month is beyond normal.” While several MMM recruiters were arrested in India in mid-2013, MMM continued to sponsor charity events and host webinars there. As recent as April 3, MMM hosted a talk in Baroda Gujarat, India where attendees were informed on the MMM ideology and cryptocurrency before being offered a free lunch.

Lithuania is one of the few countries that successfully shut down MMM. Officials noticed MMM when they saw it opening websites in Lithuanian and advertising in public spaces. The Bank of Lithuania contacted the Police and Prosecutor General’s Office to request a formal investigation, and it also sought out the marketing agencies running MMM advertisements and requested removal of the ads.

The police department soon determined that MMM was a Ponzi scheme and five people were arrested. Luckily for the approximately 1,500 participants in Lithuania’s MMM program, prosecutors used the recovered assets from those arrested to pay back their losses. MMM’s Lithuania site is no longer active.

Lithuania’s aggressive efforts are a unique success against MMM. Other regulators around the world do not have the resources, expertise, or apparent appetite to execute such a coordinated assault against the organization. If the MMM country websites shutdown and all future investors find a nationless cryptocurrency instead, it’s even more unclear which authorities would have the responsibility and authority to act. But while regulators’ inability to curb MMM’s growth is troubling, the more challenging question is why, given all of the unsavory public information available on MMM, do so many people invest?

A question of trust

Blaming the naivety of MMM’s participants is an easy, albeit unsatisfying, answer. It’s true that many Russians like Khodorych have a limited understanding of financial instruments and investments. A similar lack of knowledge also describes participants in many of the other emerging markets where MMM took root like Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Zimbabwe. But even in these disparate places, there were still relatively savvy and well-educated participants like Borisevich. There were also MMM sites in rich nations with strong public education systems, like Australia and Japan.

Local culture can sometimes contribute to a certain admiration for MMM, rather than derision. British news producer Peter Pomerantsev wrote in his book Nothing is True and Everything is Possible: Adventures in Russia, that “the premise for most Western shows is what we in the industry call ‘aspirational’: someone works hard and is rewarded with a wonderful new life. The shows celebrate the outstanding individual, the bright extrovert. But in Russia that type ends up in jail or exile. Russia rewards the man who operates from the shadows, the gray apparatchik.”

“You can tell a lot about a culture from its fairytales,” said Nechaev, Russia’s former Minister of Economics. “The Germans have dwarves that go and work hard in the mountains. [In Russia] we have fairytales about Ivanushka, a man who lays on his couch all day and then finds a golden fish. MMM would help you to find the golden fish.”

There are also structural weaknesses at work in Russia and the other countries where MMM operated most successfully. A severe lack of trust in institutions means people cannot assess who they can rely on. “People trust government relatively more than other institutions, but not because they actually trust the government—it is just the lesser evil,” says Marina Krasilnikova, a director at the Levada Center, one of Russia’s only independent public opinion polling organizations. In this sort of atmosphere, the risks and the associated returns between an untrusted bank and an untrusted investment scheme may not seem that far apart for some people. Neither may be solvent in a year, but at least the latter offers a much better return.

Part of the reason there’s demand for Ponzi-scheme-style investments in India could be because there’s not much alternative. According to the Reserve Bank of India, in the past a lack of bank branches in rural areas prevented 40% of citizens from accessing basic formal financial services, and even now only about 50,000 out of 600,000 villages in the country even have bank branches. Indians may simply find it logistically easier to give their money to an investment scheme like MMM, whose representatives show up in their village offering free food and opportunities to double their money, than a formal banking institution. Likewise, more than 20% of Russia’s population is considered “unbanked,” according to Morgan Stanley research.

All of these factors can explain how a Ponzi scheme like MMM can persist. Yet, there seem to be more primal, universal underpinnings for the extraordinary growth of a scheme like MMM in even rich nations. Every part of your clearheaded self might see the risks and think that MMM should be avoided. But after you spend time with people like Alexey Khodorych and Pavel Borisevich, you become curious. Perhaps their modern-day equivalent is the friend everyone has who made a pile of money on bitcoin. What once seemed like a hapless risk becomes a more reasonable bet that you see others taking—and winning. After a while, like Boresevich’s father, you start to wonder why you haven’t joined in. What if you’re missing out?

Charles Kindleberger, an economist who authored the celebrated treatise on historical money schemes, Manias, Panics, and Crashes, wrote that “there is nothing so disturbing to one’s well-being and judgment as to see a friend get rich.” This is as true for the average Indian, Malay, or Russian today as it was for Dutchmen during the tulip mania in the early 1600s or Brits during the South Sea Bubble. Most Russians watched wistfully as some of their former buddies became oligarchs; they struggled, and continue to struggle, to catch up.

Pivot to crypto

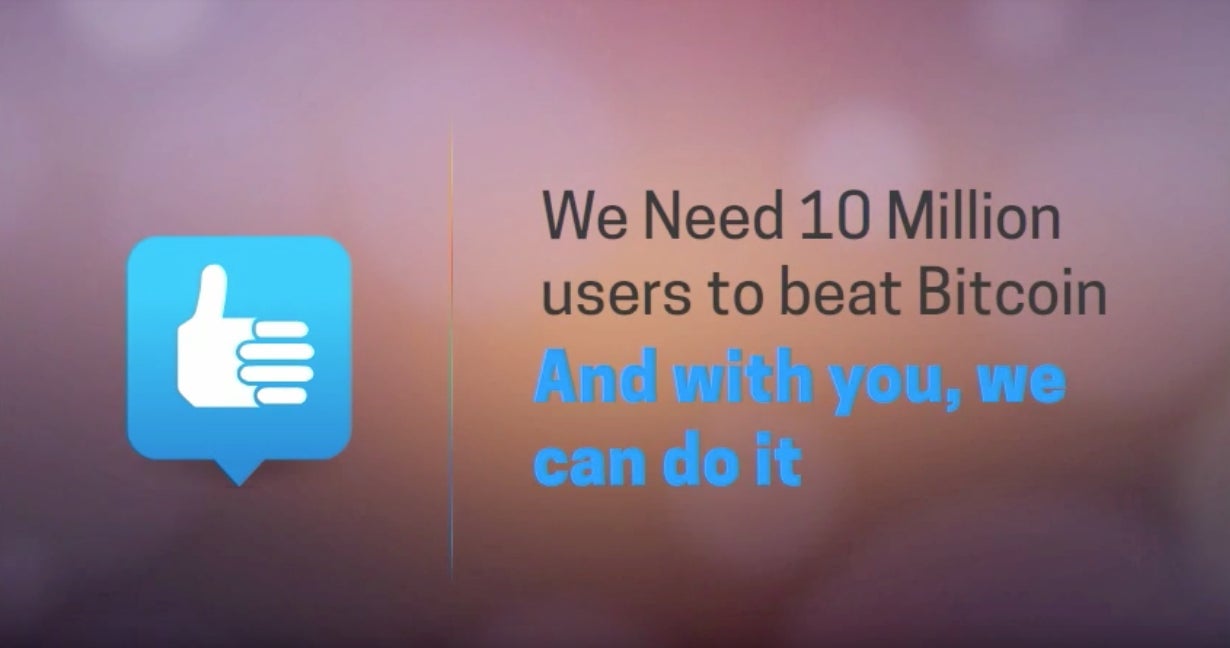

Meanwhile, bitcoin and its offshoots, the latest financial mania, also play into these impulses. It’s not surprising, then, as hype about stateless digital assets builds, MMM has gotten in on the act. An initial coin offering (ICO), which blends aspects of crowdfunding and cryptocurrency trading, has picked up the Mavro and MMM branding. The fundraising project, designed for the “multi-level marketing industry,” includes a picture of Mavrodi on its website, though it’s unclear whether he was ever actually involved.

In response to questions about the ICO before Mavrodi’s death, an anonymous email from the website said he was “staying in the shade” for “security reasons.” The writer said previous MMM programs were corrupted by people who used his name to scam people, but “now, there is an amazing opportunity due to blockchain technology.”

Today, while the MMM country websites announce closures, the homepage of the MMM Coin website identifies itself as “the latest of Mavrodi’s various program,” and adds that “he wants to beat Bitcoin and make MMM Coin the No. 1 coin in the world.”

Unlike the “low risk, high return” pyramid schemes used by Ponzi or Madoff, MMM has perpetuated a uniquely dubious product. It overtly advertised its risks and promised nothing in return. Still, people like Borisevich and millions of others invested. Mavrodi tapped into something that’s deeply embedded in our psyche—the desire to have more, and the fear of being left out. People like Mavrodi didn’t create that defect, but they feed on it.

As for Mavrodi, he reportedly died of a heart attack in Moscow. Some dispatches indicate he was taken to the hospital from his apartment, while another says he was rushed into care from a bus stop. With Mavrodi, you can seldom be sure what really happened. Now that he’s gone, it seems appropriate that opportunists in the crypto world, which has its own reputation issues, are trying to carry on his legacy.

A few years ago, when we asked about his plans for the future of MMM, he wrote back: “You’ll see. Along with all the other people. :-)”