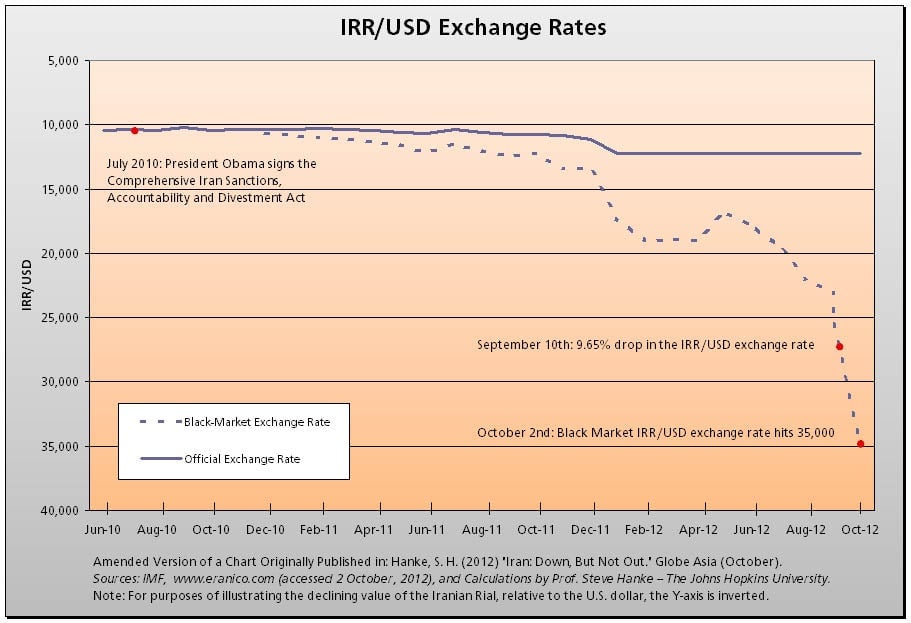

How President Obama, a Belgian payment system, and the EU just killed Iran’s economy

Iran’s currency is falling to pieces.

Iran’s currency is falling to pieces.

Why now? After all, the Islamic Republic has faced nearly 30 years of sanctions.

To understand why Iranian money is getting a lot weaker, you have to understand a little bit about how the country’s economy works. Oil sales are, by far, Iran’s largest source of economic activity and government revenue. But they’re also the country’s only major source of hard currency. A hard currency is one that’s widely viewed as a reliable story of value. The world’s pre-eminent reserve currency, of course, is the US dollar.

Access to a supply of greenbacks and other hard currencies is crucial for countries that have capital controls in place to keep their currencies strong. One of the roles of the Central Bank of Iran is to use its stockpile of hard currency to keep the value of the rial where it wants it to be. If officials feel there are too many rial floating around–risking a breakout of inflation or widespread disruptive price increases–it will forcibly use its dollars to buy rial. That pulls rial out of the economy–reducing supply–and pushes dollars in, boosting the supply of greenbacks. If there are fewer rial and a lot more dollars floating around the economy, that effectively makes the rial stronger.

China uses a similar process to keep its currency from getting too strong, which would hurt its export economy. Using its massive stockpiles of dollars–earned in its huge trade surplus with the US–the Bank of China will buy or sell American dollars to keep its currency from strengthening or weakening too much.

But here’s the thing. China has a massive stockpile of dollars. On the other hand, many think that Iran’s hoard of greenbacks is shrinking fast, and as a result, they believe the Central Bank of Iran has stopped propping up the Iranian currency. The Iranian people now realize it. And they’re desperately trying to convert their money to something else.

But again, why now? Why is Iran finding it increasingly difficult to get hard currency? The answer seems to be some of the most recent sanctions have proven enormously effective. President Barack Obama may be able to take a bit of a victory lap on this one, having in February signed an executive order sanctioning wide swathes of the Iranian financial system, including the Central Bank. Since the Central Bank is so, well, central, to propping up the currency this is likely playing an important role.

Another interesting element was the March 17 move by the Belgium-based Society for Worldwide International Financial Transfers (SWIFT) to cutoff any Iranian banks blacklisted by the European Union. Not long after the SWIFT cutoff things started rapidly going downhill for the rial. And finally, the European Union embargo on buying Iranian oil took full effect in July. The outcome? The Congressional Research Service says:

Together, these sanctions have reduced Iranian oil exports to about 1.4 million barrels per day as of late August 2012, down from an average of 2.5 million barrels per day for all of 2011. This loss of sales has caused Iran to reduce oil production, to the point where it is producing less oil than is Iraq. Iran is widely assessed as unable to indefinitely sustain this level of lost oil sales, although it does have a large foreign currency reserve fund that can, at least temporarily, mitigate the impact of the lost oil revenue.

As we mentioned above, the recent sharp decline in the rial suggests that Iran’s currency reserve might not be that ample after all.