New clashes between Buddhist extremists and Muslims occurred in two different towns in Sri Lanka, Kandy, and Ampara in early 2018. Triggered in part by hate-filled posts spread by nationalistic Sinhala Buddhist Facebook groups, these riots resulted in the death of one Muslim and the destruction of many buildings.

To many non-Buddhists outside Asia, this sort of violence can seem surprising. Westerners think of Buddhism as a peaceful religion, folding Buddhist terms and practices into stress relief practices such as mindfulness. But like any religion, Buddhism has a far more complicated story than that—and Sri Lanka has seen many disturbing and violent episodes that attest to that fact.

The Buddhist Protestantism of the 19th century, the monks who invoked Buddhist texts to justify the Sri Lankan civil war, and the extremist movements surging today all have one thing in common: a belief that Sri Lanka is a Buddhist nation that must be protected from foreign elements, violently if necessary. The Sri Lankan case shows that nationalism and extremism can be filtered through anything.

Buddhist revivalism in the early 20th century

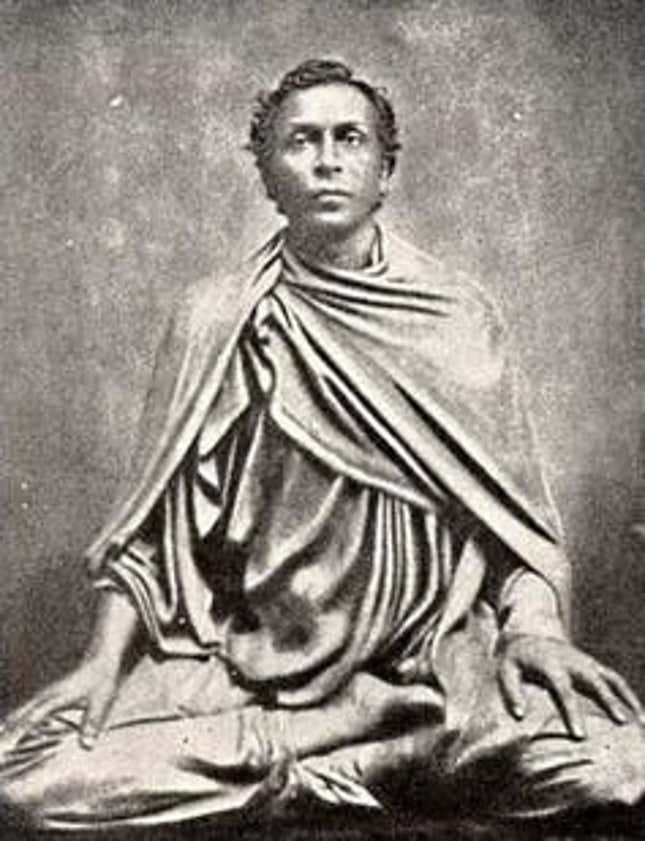

The movement known as Buddhism revivalism or Protestantism in Sri Lanka started with Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933). Known as the father of Buddhist Protestantism in Sri Lanka, Dharmapala had an anti-imperialist and nationalist agenda. Besides fighting the British, who ruled Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) at the time, Dharmapala focused on founding Buddhist schools and strengthening the Sinhala language and Buddhism in Sri Lanka’s public sphere.

To this day, Sinhala nationalists portray him as a hero and their saviour from “the evil influence of Western domination”; his birthday is celebrated every year in the Sri Lankan media, reminding people of the deeds of a national hero.

In 1915, police changed the original route of a Buddhist festival procession in order to prevent them from passing a mosque. Mockery by Muslims did not help the matter, and riots soon erupted in Sri Lanka, pitting Sinhala Buddhists against Muslims. 25 Muslims were killed, around 200 were injured, mosques were damaged, and many businesses belonging to Muslims were destroyed. The British were accused of killing both Sinhala and Muslims when they tried to stop the riots, providing the spark that ignited the Sri Lankan independence movement.

Buddhism and the civil war

Between 1983 and 2009, Sri Lanka was plagued by a civil war between the Sinhala government and Tamil (mainly Hindu) rebels. The war had numerous causes, but prominent among them were government moves to embrace religious nationalism.

After they won independence from Britain in 1948, Sri Lanka’s politicians started to enforce the use of the Sinhala language across the country’s public institutions, making it the official language. They also inserted Buddhism into the constitution: “The Republic of Sri Lanka shall give to Buddhism the foremost place and accordingly it shall be the duty of the state to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana.”

This angered Sri Lanka’s Tamil-speaking minority. Militant student organisations were soon formed with the aim of forming a new Tamil homeland. In July 1983, also known as Black July, Tamil rebels killed a number of soldiers from the Sri Lankan army. During subsequent riots, various Sinhala mobs killed many Tamil civilians. The civil war was now a fact.

Buddhism was invoked to justify the war in various ways. In her book, In The Defence of Dharma: Just-war Ideology in Buddhist Sri Lanka, religious studies professor Tessa J Bartholomeusz offers some examples. To take just one, a Sinhala army song from 1999, said to be composed by a Buddhist monk, contained the following verse:

Linked by love of the [Buddhist] religion and protected by the Motherland, brave soldiers you should go hand in hand.

But it wasn’t just the army; everyday people and monks also used Buddhist texts and used military metaphors. Some Buddhist monks extolled warrior virtues as stemming from Buddhism:

That Buddhism is a religion of ardent aspiration for the highest good of man is not surprising. It springs out of the mind of the Buddha a man of martial spirit and high aims … Buddhism … is made by a warrior spirit for warriors.

After the war

When the civil war ended in 2009, many hoped that Sri Lanka’s ethnic groups would find a way to coexist in peace. But it didn’t take long before the country’s Buddhist extremists found another target.

Currently, Sri Lanka’s most active Buddhist extremist group is Bodu Bala Sena (Buddhist power force, or BBS). The BBS entered politics in 2012 with a Buddhist-nationalist ideology and agenda, its leaders claiming that Sri Lankans had become immoral and turned away from Buddhism. And whom does it blame? Sri Lankan Muslims.

BBS’s rhetoric takes its cue from other populist anti-Muslim movements around the globe, claiming that Muslims are “taking over” the country thanks to a high birth rate. It also accuses Muslim organisations of funding international terrorism with money from Halal-certified food industries. These aren’t just empty words; in 2014, one of their anti-Muslim protest rallies in the southern town of Aluthgama ended with the death of four Muslims.

BBS also has links to Myanmar’s extremist 969 movement. Led by nationalist monk Ashin Wirathu, who calls himself the “Burmese bin Laden”, it is notorious for its hardline rhetoric against the Rohingya Muslim community.

It is hard to say if these latest events really do represent a global trend, but it’s deeply ominous to see extremist organisations collaborating across borders. Sri Lanka and Myanmar aren’t the only countries where this is happening; Thailand is also often mentioned as a hotbed of increasingly belligerent Buddhist extremism. Perhaps the next violent riots to pit Buddhists and Muslims against each other will be taking place in yet another country.

Andreas Johansson, director of Swedish South Asian Studies Network (SASNET), Lund University. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.