China’s new chip investment fund shows how US penalties on Chinese firms can backfire

One of the challenges the US faces in its trade spat with China is how to enforce penalties on Beijing for actions it perceives as anti-competitive, without causing Beijing to double down on those behaviors to boost its economic self-reliance. Case in point: China’s semiconductor industry.

One of the challenges the US faces in its trade spat with China is how to enforce penalties on Beijing for actions it perceives as anti-competitive, without causing Beijing to double down on those behaviors to boost its economic self-reliance. Case in point: China’s semiconductor industry.

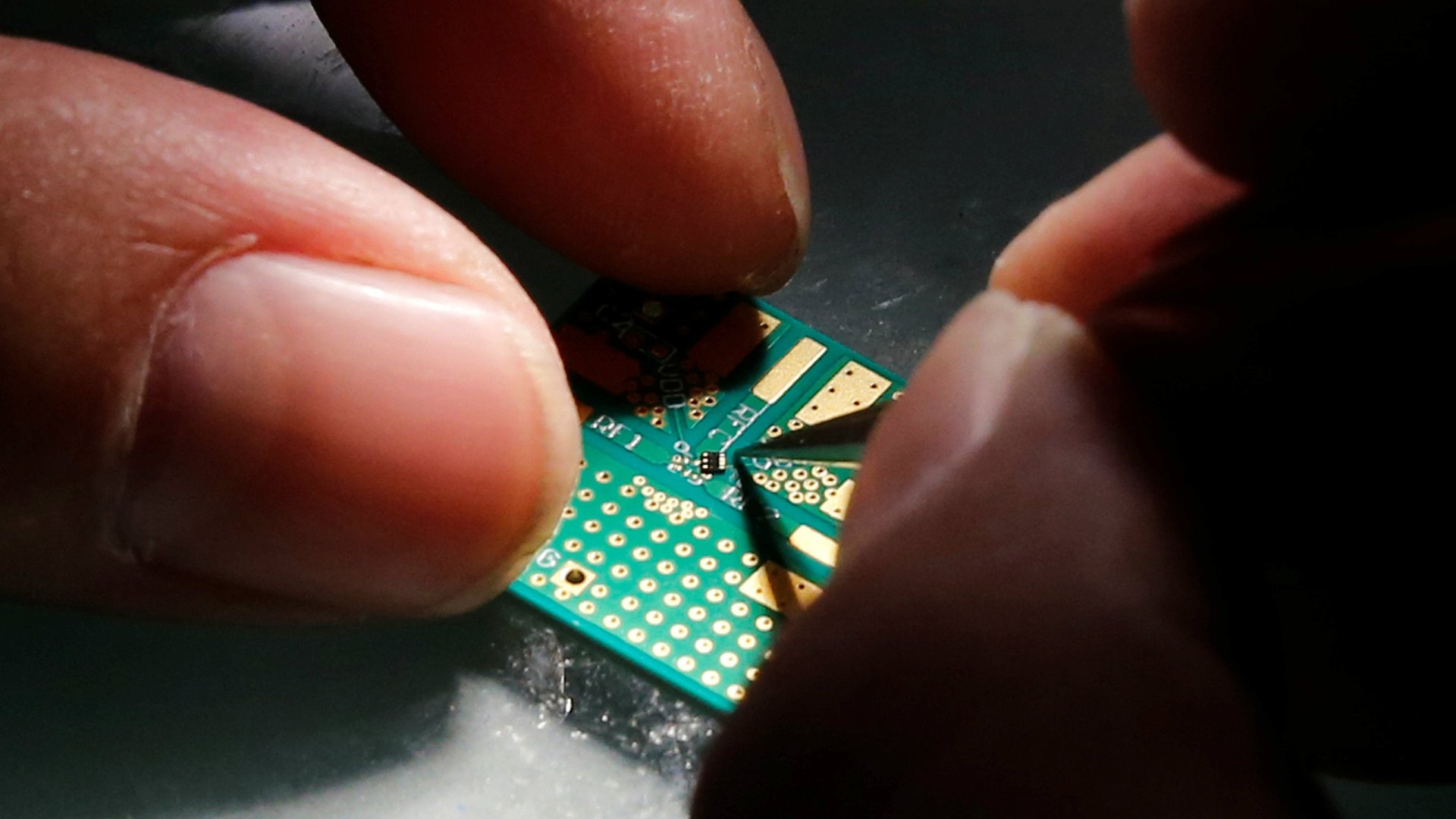

Beijing is in the process of closing a massive fund for the development of semiconductor technology, in an effort to foster domestic chipmakers that can compete with US-based rivals. According to the Wall Street Journal (paywall), the fund will be valued at about 300 billion yuan ($47.4 billion).

It will be the second fund for China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund Co., which counts the country’s finance ministry and a state-owned development bank among its backers. Its first, launched in 2014, had 139 billion yuan (then $21.8 billion) in capital. Some of that money went into Tsinghua Unigroup, a Beijing-based chipmaker best known for its failed attempt to acquire US-based Micron Technology.

News of the second fund surfaced earlier this year. It looks set to close just as US-China tension over technology and trade reaches a critical stage. Last month, US authorities ordered American chip companies to stop supplying components to ZTE, a Shenzhen-based maker of smartphones and network equipment. They argued ZTE failed to comply with an agreement made a year ago after the firm pleaded guilty to violating export sanctions placed on Iran and North Korea.

The ban will cripple ZTE in the short term, primarily because it relies on Qualcomm, a US-based chipmaker, for processors. While other vendors, either Chinese or non-US, can replace some of the components in ZTE’s phones, no Chinese chipmaker can come close to Qualcomm when it comes to making competitive semiconductors.

Last month Chinese state media outlets ran editorials citing the decision by US authorities as a reason for China to become more self-reliant when it comes to technology. China consumes about 45% of the world’s semiconductors. But nearly 90% of the chips used in the country (paywall) are imported or made by foreign firms operating within its borders.

Most experts believe that China has not yet caught up to the United States when it comes to semiconductor technology. But punishments like export controls could expedite China’s efforts to get its domestic counterparts up to speed with their rivals. And if they do catch up, then Qualcomm, Micron, and other US chipmakers could lose access to a massive market in China, and face stronger Chinese competition elsewhere. In the smartphone industry, for example, China remains the largest market, and three of the world’s top five brands hail from China.

Technology advisors to the Obama administration suggested in early 2017 (pdf), before Trump took office, that Beijing’s heavy involvement in its semiconductor industry, either through funding or forced technology transfer, amounted to unfair competition. It also warned that Chinese leadership in chips would “increase national-security risks for the United States and other countries and, to the extent that Chinese policy allows firms to sell below cost of production, raises risks of overcapacity, which threatens direct competitors.”

Yet it’s difficult to see punitive measures taken against China’s trade practices doing anything but further emboldening the country to rely on itself, not others, for its technology ambitions.