Uber is done demanding silence on sexual harassment

Last month, Susan Fowler, the former Uber engineer who authored a 2017 viral blog post about sexual harassment she endured while working there, penned an op-ed for the New York Times on how to terminate such behavior. “We need to end the practice of forced arbitration,” she wrote on April 12, “a legal loophole companies use to cover up their illegal treatment of employees.”

Last month, Susan Fowler, the former Uber engineer who authored a 2017 viral blog post about sexual harassment she endured while working there, penned an op-ed for the New York Times on how to terminate such behavior. “We need to end the practice of forced arbitration,” she wrote on April 12, “a legal loophole companies use to cover up their illegal treatment of employees.”

Now, in a surprising turn, her former employer is doing just that. Uber will no longer require its US riders, drivers, or employees to arbitrate individual claims of sexual assault or harassment, chief legal officer Tony West announced today (May 15). The company will also stop requiring confidentiality provisions on claims of sexual misconduct. Uber said the changes won’t unwind previous settlements, but will apply to all future complaints, effective immediately.

The legal overhaul puts Uber, which a year ago was regarded as one of the most toxic workplaces in Silicon Valley, at the forefront of a movement to change how sexual harassment is handled in corporate America. The company said it also plans to begin publishing a publicly available “safety transparency report” with data on sexual assaults and other incidents that occur on the Uber platform. “The last 18 months have exposed a silent epidemic of sexual assault and harassment that haunts every industry and every community,” West said in a statement. ”Uber is not immune to this deeply rooted problem, and we believe that it is up to us to be a big part of the solution.”

Binding arbitration agreements, which have individuals forfeit their right to sue in court, are ubiquitous in the technology industry. They typically go hand-in-hand with nondisclosure agreements (NDAs); together, the two legal provisions ensure that disputes are kept quiet and confidential. These agreements can help companies avoid costly, protracted legal disputes but they also tend to protect bad behavior. In complaints involving sexual misconduct, arbitration and nondisclosure agreements often have a chilling effect: Technically, you can still bring a complaint to court, but the agreements enable the company to argue that the case was subject to binding arbitration, and a judge would likely agree. That often forces victims to remain silent, and prevents them from warning others about the alleged harassment.

The now-famous account Fowler published in February 2017 plunged Uber into an existential crisis that ultimately led the company’s board to push out co-founder and then-chief executive Travis Kalanick in a messy power struggle. Fowler described a direct manager who propositioned her, an engineering team that bled female talent, and a human-resources department that systematically dismissed her concerns in order to protect “high performers.”

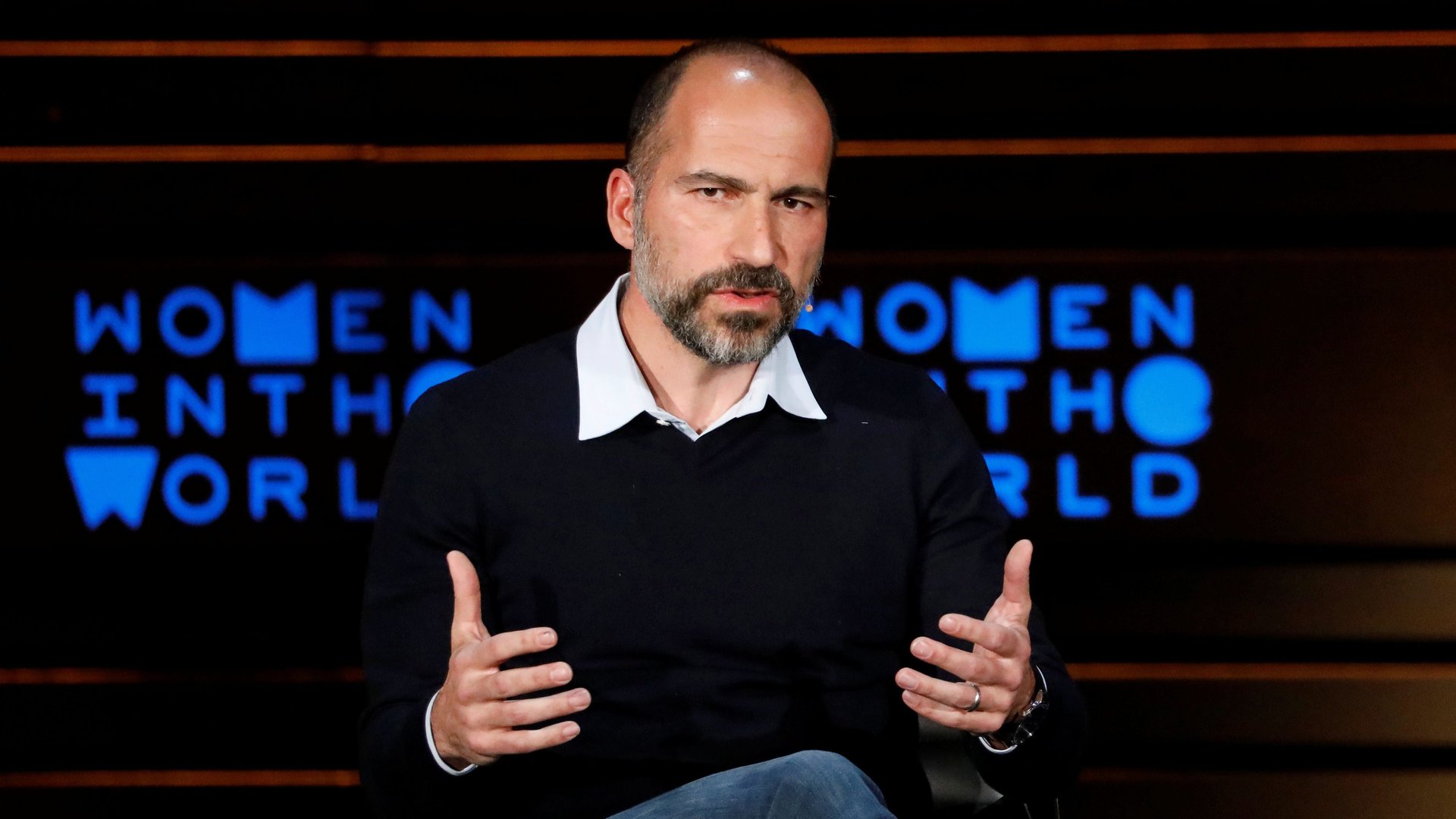

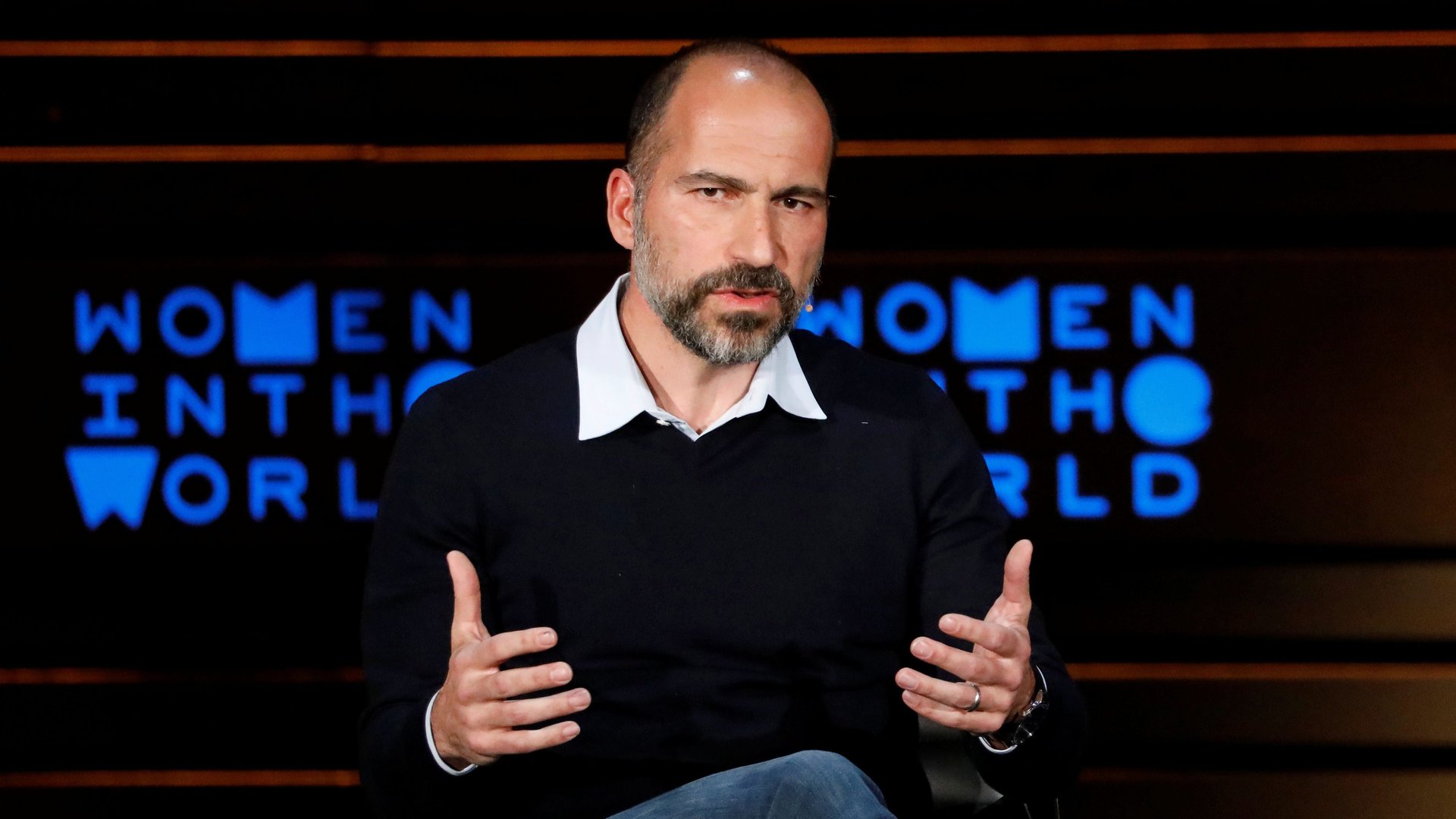

A day after Fowler’s report went public, Uber hired Eric Holder, a former US attorney general under president Barack Obama, to investigate allegations of sexual harassment. In early June 2017, it fired 20 employees after a separate probe by law firm Perkins Coie. Kalanick resigned later that month. Dara Khosrowshahi, appointed Uber CEO in late August 2017, has made cleaning up the company culture a priority since taking over the job.

Arbitration clauses and nondisclosure agreements have long been business-as-usual in corporate America, but sentiment has begun to shift. Last year, sexual-harassment claims toppled dozens of powerful men, from Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein and television host Charlie Rose to several prominent venture capitalists. The ensuing #MeToo movement has fueled efforts among lawmakers to to revise the conventional wisdom on how to handle sexual harassment complaints.

“Nondisclosure agreements are fading fast as an acceptable tool for settling sexual harassment cases,” Suzanne Goldberg, an expert on gender and sexuality law, and professor at Columbia Law School, said in an email. “It is painfully clear that NDAs have hidden far too much wrongdoing from public scrutiny and, in some settings and with some people, have enabled serial harassment to go on for years or even decades.”

In early December, a bipartisan group of US senators introduced legislation to Congress that would void forced arbitration agreements in workplaces that silence victims of sexual harassment. Later that month, Microsoft said it was ending forced arbitration agreements for employees making sexual harassment claims, and expressed support for the bipartisan bill. This past February, all 50 US state attorneys general signed a letter to Congress calling for lawmakers to ban employers from mandating arbitration for sexual harassment claims in the workplace.

While scandals at Uber’s corporate offices have taken center stage, the company has also faced plenty of other well-publicized harassment and assault allegations from members of its ride-hailing platform. Internal data viewed by BuzzFeed in 2016 showed thousands of customer-support tickets with the phrases “sexual assault” or “rape” from December 2012 to August 2015. An April 2018 CNN search of police and court records in 20 major US cities found that 103 Uber drivers had been accused of sexual assault over the previous four years; 31 drivers had been convicted and dozens of others faced criminal and civil cases at the time.

In November 2017, two women in California filed a class-action lawsuit alleging that Uber’s “woefully inadequate background checks” had created a platform that exposed thousands of female passengers to “rape, sexual assault, physical violence, and gender-motivated harassment.” In March 2018, Uber came under fire after court records showed it had tried to push the women in that case toward individual arbitration. “Arbitration is the appropriate venue for this case,” an Uber spokesperson said at the time. The company’s revised policies, in addition to not being applied retroactively, also don’t apply to class-action claims. That means victims who wish to file lawsuits about harassment will still have to do so individually, and will still not be able to bring a case on behalf of many plaintiffs.