Solving Mexico City’s cataclysmic cycle of drowning, drying, and sinking

Pedro Camarena was standing inside a hole in the ground big enough to bury his full-size pickup truck. It was a late April afternoon in the middle of Mexico City, and the metropolis was on the cusp of its rainy season. In a few weeks, the past eight bone-dry months—so parched that unaccustomed visitors often get nosebleeds—would give way to four months of deluge.

Pedro Camarena was standing inside a hole in the ground big enough to bury his full-size pickup truck. It was a late April afternoon in the middle of Mexico City, and the metropolis was on the cusp of its rainy season. In a few weeks, the past eight bone-dry months—so parched that unaccustomed visitors often get nosebleeds—would give way to four months of deluge.

At the bottom of the hole, a ripple of black, porous rock told a story of magma once in motion. Beside the ripple, a bulb of lava rock marked a spot where magma flow may have hit water, formed a bubble, and hardened just as it was set to pop, a spectacular moment of generative violence. The hole is a sort of time portal to roughly 1,700 years ago, when waves of lava from the nearby Xitle volcano coursed over this plateau. It’s a time all but forgotten by the megacity that grew up and engulfed the landscape. But Camarena hasn’t forgotten. He stood in his hole and beamed.

In Mexico City, many sections of the 21-million-person metropolis have no reliable running water. The hole, Camarena believes, is where experts will find an answer to this crisis.

The worst possible place to build a megacity

To understand how this happened, one needs to understand Mexico City’s perverse relationship to its geology. The city was built on bad choices, given it sits on an unstable crust of clay and a swath of lava rock. Clay and lava, nearly all paved over—it’s the worst possible combination.

An hour earlier, Camarena, a landscape architect at Mexico’s National Autonomous University (UNAM), sat onstage in an auditorium in the science department giving a talk titled “A day zero for water. Cape Town, and Mexico City?” He sounded tired, like he’d said this all before.

The water crisis in Mexico City, like the water crises in many cities, is a story of epic multigenerational mismanagement. Consider Cape Town, South Africa, which, in early 2018, barely averted a “day zero.” Scientists had been warning the public and policymakers that a drought Cape Town’s system couldn’t handle was inevitable; their warnings grew more dire in the three years leading up to the “day zero” scare, when winter rains barely fell. The national government allegedly ignored the experts, failing to curtail the use of agricultural water as the drought set in. The city government, meanwhile, failed to invest in necessary water-security projects, balking at their cost. It was “a situation that the city’s bureaucrats believed would resolve itself,” as the Atlantic put it. Until it wasn’t.

In Mexico City, the problem goes back to some of very first decisions made by Spanish invaders in the 1500s. The lakes were once the area’s primary source of freshwater, and the Aztecs managed seasonal flooding with a network of levees and canals. The most prominent of these lakes was Texcoco, surrounding the island on which the Aztecs built the city-state (and their eventual capital) of Tenochtitlan.

After the Spanish seized Tenochtitlan, they drained the lake, destroyed the Aztec city, and built their own in the European style, which turned out to exacerbate seasonal flooding. The City of Mexico would fill up like a cup in the rainy season—it was once underwater for five years. But the Spanish continued to drain the lake system, and the city took deeper root atop silty-clay lakebed. Now, Texcoco and all the other lakes are gone, with the exception of a few marshlands and a region of canals in the south of the city.

Planners now know that was a recipe for more floods. The bowl-like depressions where the lakes once stood had no natural exit for water, and the denuded forests, whose soils once acted as sponges for flood water, no longer served as a buffer between water and people.

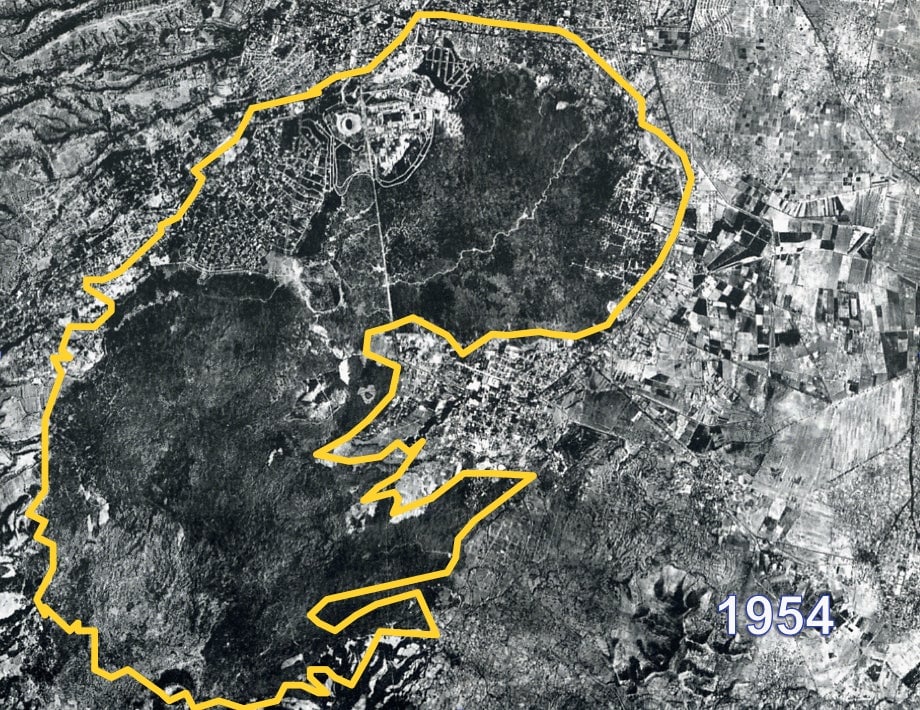

Camarena’s presentation included a series of slides showing the lakes progressively reduced to smaller and smaller pools of blue, chased at their heels in each slide by encroaching urban sprawl until the telltale geometry of a city filled the frame. When he showed these images, a woman in the front row gasped.

A sinking feeling

Without the lakes, Mexico City turned to the groundwater for drinking water.

The groundwater was, and still is, stored in the relatively shallow aquifers that lie beneath the lake beds. In theory, groundwater can be replenished, but it’s a slow process; before rainwater can refill an aquifer, it must fall through layers of earth and rock, past many thirsty soil layers. In fact, while Mexico City residents endure months of regular flooding during the rainy season in some parts of the city, virtually none of that water makes it underground. That’s because rapid urbanization has sealed up any permeable surfaces in the city with pavement. In short, the city’s pores are clogged.

The math is simple: If you pump water out faster than the rainwater can trickle back in, the aquifer runs out. Mexico City already pumps out water over twice as fast as it can be replenished, and the population of the city continues to grow. A decade ago, it was nearly half of the 20 million it is now, according to UN data. Mexico City’s aquifers have become bank accounts on the verge of being overdrawn.

All that pumping is literally sinking the city. As the city drains water from the aquifers, empty space is left in its wake. The ground, now without structural integrity, sags into that void. In some places Mexico City is subsiding as much as 15 inches (38 cm) per year. For comparison, the famously sinking Italian city of Venice is sinking at a rate of less than half an inch per year. Over the last century, experts estimate, Mexico City has sunk around 33 ft (10 meters).

All over the city (most iconically in the historic center) buildings and churches lean like drunken men, the land having made an uneven descent into the earth beneath their foundations. Giant sinkholes open up without warning, swallowing parts of roads and sometimes people. Cracks open in the street, and buildings collapse or become too unsafe to inhabit. It’s a chronic threat in Iztapalapa, a poor neighborhood in the city’s southeast, home to some 2 million people; elementary schools in Iztapalapa have crumbled, according to the New York Times.

Tap water is unreliable all year long in places, and rampant contamination means few can trust what comes out of their taps. Families have to pay for “pipas,” or water trucks, to come fill up cisterns. Some pipas are run by the government, while others are privately managed. In both cases they’re inundated with corruption and more demand than they can handle, according to a New York Times report from 2017. The job of waiting for the pipas goes mostly to women, and the hours of waiting and the threat of not getting water leaves many women from the poorest neighborhoods unable to work outside the home.

Then, in the rainy season, parts of Mexico City flood. The same neighborhoods where families go broke paying for water deliveries often contend with floodwaters in their living rooms in the wet months. And climate change is set to make this brutal cycle more punishing. Temperatures are rising, which will make every part of the water system thirstier, and both the rainy and dry seasons more extreme.

Lava city

Not all of Mexico City was built on lakebed. Southwest of the city center is a region now known at the Pedregal, which rests on hardened lava flow.

Up until some 1,700 years ago, and for a thousand years before that, the area housed Cuicuilco, one of the oldest metropolitan cities on the North American continent. Then Xitle erupted and engulfed most of Cuicuilco in lava. Historians date the decline of the Cuicuilco civilization to around the same time. Today, the city’s ruins are still presumed trapped under the volcanic rock and soil.

Fast forward to the 1940s: Mexico City was growing fast, and the burgeoning bohemian artist class saw the Pedregal as an ideal rural retreat: a still-wild place away from the bustle of the city, and a truly Mexican landscape amidst a metropolitan area dominated by colonial Spanish design. The famous modernist architect Luis Barragan began buying land there in 1943, and artist Diego Rivera, who painted scenes of the Pedregal’s unique flora, praised its “constitución volcánica” as a more stable option to the rest of the flood-plagued, earthquake-prone Mexico City. Over the next three decades, Barragan built a series of upscale modernist homes, gardens, and plazas on the craggy terrain, construction meant to complement the unique lava ecosystem and take advantage of the drainage offered by the porous lava rock.

But at the same time, the rest of the growing city needed a place to expand. The population of Mexico City tripled between 1950 and 1975. Pedregal land, which up to this point was mostly regarded as an uninhabitable rock heap, was cheap. Developers saw a gold mine, and subdivided large lots into high-end residential communities.

Meanwhile, those living on the opposite end of the economic spectrum in Mexico City also saw opportunity, and informal housing flourished. In the 1970s, activists organized a grassroots campaign to settle the Pedregal for people who could not otherwise afford to buy property; they split land up into family-sized plots and delineated zones for streets and public space, then instructed families to move in and occupy the land as quickly as possible to avoid eviction. Hundreds of families rushed the Pedregal over a short period, built their houses, and started neighborhoods.

To this day, part of the Pedregal is a rich neighborhood full of posh houses, and part is poor; The juxtaposition makes the Pedregal a microcosm of the massive wealth gap and rigid class system that exists in Mexico City at large.

In any case, the rapid growth of the southwestern part of Mexico City would have unforeseen consequences for the entire metropolitan area. Between the mid-1950s and and mid-1980s, nearly the entire dark swath of volcanic rock that once covered the Pedregal region—comprising roughly 8,000 hectares (31 square miles)—was swallowed up by streets and buildings. The unique ecosystem was almost entirely paved over. Those 30 years are one reason Mexico City is running out of water.

After his lecture, Camarena drove his pickup truck the short distance from the science building to the one-square-mile (2.5-square-kilometer) Pedregal Reserve—the last remaining slice of undisturbed lava-rock ecosystem.

On the way, he passed a group of 30 people holding signs and chanting slogans. They were protesting Conagua, the federal water agency. In 2014, the nature preserve adjacent to their neighborhood had been chosen as the site of a new $14 billion international airport. The government drained what had been a marshy wetland, a remnant of the once-massive Texcoco lake system. As a result, the site has been sinking at a rate of between eight and 12 inches (21 to 30 centimeters) per year since 2015. In exchange for dramatically altering the landscape (and paving over sites holy to indigenous people, Camarena says) the federal government guaranteed water infrastructure. But the community has evidently not seen those projects come to fruition yet; they held signs demanding the public works they were promised.

Unclogging Mexico City’s pores

Camarena wants Mexico City to rip up sections of pavement throughout the Pedregal to expose the rock below. If rainwater could reach the porous lava rock and lava soils below the pavement, it would drain down to the aquifers below, and filter a lot of contamination along the way. The hardened lava flow “sucks it up like a sponge,” Camarena says.

He is conducting some of the first research to figure out how effective the Pedregal could be in solving Mexico City’s water woes. But funding has been tight, so Camarena has had to get creative. In a perverse twist of luck, Camarena caught a construction company dumping debris inside the reserve a few months back. Instead of calling the police, he cut a deal: If the construction company agreed to move 20 dump trucks-worth of debris off of the site where Camarena’s team wanted to excavate, they wouldn’t have them arrested. So now they have their research hole, Camarena explains while standing, grinning, about three meters below ground.

Camarena and his team at UNAM are trying to figure out how much time and money would be needed to re-expose some of the lava rock on a larger scale, in parts of the Pedregal where it’s trapped beneath highways and parking lots. Could you take out a concrete median on a highway, and let falling rain hit lava rock below? Could you peel back the city’s decorative lawns, and make lava-rock gardens instead?

It would be a herculean task; in parts of the Pedregal outside the reserve where the rock is covered by soil, not cement, an invasive African grass has grown like a mat, choking out the soil’s ability to let water through. All that soil would need to be moved out. “It would be extremely hard to re-expose the Pedregal,” Camarena says.

But it’s still easier than the most obvious alternative: building a second pipe to pump water from some far-off source into the city center to supplement the dwindling aquifers. Mexico City already has one such pipe system, which uses vast amounts of electricity to pump in water from a reservoir system in Cutzamala, more than 100 km (60 miles). It’s also highly inefficient: by the time the piped-in water makes to people’s homes, 40% has been lost to leaks along the way.

So Camarena and a handful of others are trying to get the Pedregal idea off the ground; there may be no simpler solution to Mexico City’s water crisis. You can’t sustain a metropolis the size of Mexico City on its dwindling aquifers, and you can’t recharge those aquifers without letting the rain penetrate the ground.

Camarena doesn’t have data on how much water would sink through the rocks if they weren’t sealed up—to his knowledge, no one has done that research yet, and he’s only working on figuring out how hard it would be to re-expose the rock. But, he says, “the amount of water we are losing is big. If the Mexican government had realized this in the 1950s, I think they wouldn’t have urbanized this zone.”

Flora nativa

Deep in the reserve, there are parts of the Pedregal that have never been paved over. Here, it is like walking onto another planet. Knobby ridges of black lava rock rise as much as 10 feet high off the ground, and bristle with plants. They’re mostly species found only in the Pedregal, like a rare orchid that grows from the ground (nearly all orchids grow only from aloft, high on the sides of trees). Limp fingers of “palo loco” (“crazy wood”) trees reach up through the rock, their branches the constitution of half-cooked noodles. Native maracuja vines sprout hard fruit the size of billiard balls and covered in fuzz the color of mint ice cream. Teal-and-red “donkey ear” succulents flop open atop squat broccoli-like stems, and a rare red lily that only grows here unfurls its pointy tendril-like petals.

And this is during the dry season. Throughout these eight months of relative drought, any plant life requires in the rest of the city requires vast amounts of precious water just to squeak through. Most of the UNAM campus, for example, uses 77% of its tap water just watering its lawns in the dry season.

In the Pedregal Reserve, plants that look dead aren’t. When the rainy season hits the following month, their brown husks will reanimate and frondesce within hours. Flowering plants will bloom immediately.

“They’re made for this climate,” Camarena says. The plants are uniquely adapted to months of trying drought and punishing sun, and then months of deluge, with wildly variable day-to-night temperatures along the way, like one might find in a desert. “Not like those gardens of those idiot houses over there,” Camarena says, pointing to a collection of high-end homes perched on a ridge in the distance. “This,” Camarena says, referring to the Pedregal Reserve in front of him, “was the landscape just 60 or 70 years ago. We change things so fast.”

Later, back on UNAM’s campus, which is built on the Pedregal just outside the reserve, Camarena points with derision at an immaculate lawn. “This is the landscape of Scotland or England, not Mexico,” he says. “Even hundreds of years after the conquista we still think the European style is better than native landscape.”

So far, Camarena has been met mostly with bureaucratic resistance. He keeps a small demonstration garden of Pedregal plants—with the help of his students, since the university wouldn’t hire him a gardener. His mother used to help weed the garden, but her joints are no longer good enough for that. Camarena says the local gardener’s union, whose members tend to the campus grounds, don’t want to help his project, because it thinks switching the university’s lawns and garden beds to rocky landscapes full of Pedregal plants would put their gardeners out of work. Nothing to water, no pesticides to apply. But, Camarena argues, it would actually give them job security: In times of intense drought when lawn watering is curtailed, the campus’s gardens wouldn’t die. The gardening union would still have something to tend.

On the national scale, Camarena hasn’t yet had much luck either. He’s still trying to get funding for his research. But Mexico City’s upcoming mayoral election could change things. Water is a hot issue, and candidates’ campaigns reflect that. Take Claudia Sheinbaum, the city’s former environment minister and current National Regeneration Movement mayoral candidate, who has put forward a water strategy that promises to replant forests, install rain catchment systems on homes, and feed agriculture’s massive water demand with recycled water instead of drinking water. A project to expose ancient lava flows would fall nicely within that schema.

Meanwhile, the deprivation-inundation water cycle continues. It’s May, and the rainy season has begun, which means throughout Mexico City, women are waiting for water deliveries while sweeping flood water out of their living rooms. The Pedregal, meanwhile, is blooming in the places it still can.

Additional reporting by Zoe Mendelson.