Writing in a journal is good for you—and so is throwing it out

Very little writing withstands the test of time, and that’s fine. Take journaling and journalism for example, which seem very different. One is subjective and personal, while the other is allegedly objective and intended for an audience. But the two forms share one important quality—they aren’t built to last.

Very little writing withstands the test of time, and that’s fine. Take journaling and journalism for example, which seem very different. One is subjective and personal, while the other is allegedly objective and intended for an audience. But the two forms share one important quality—they aren’t built to last.

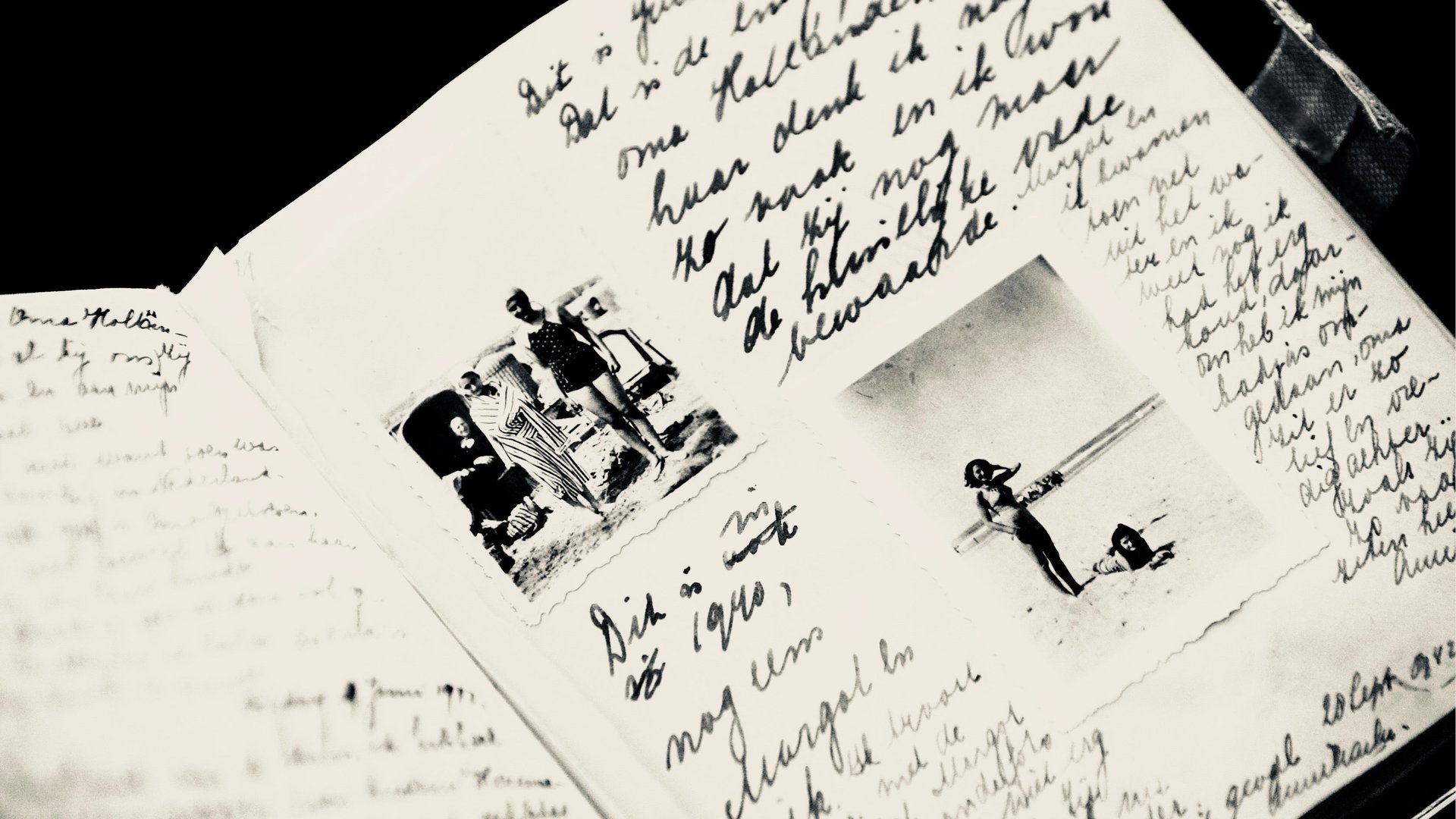

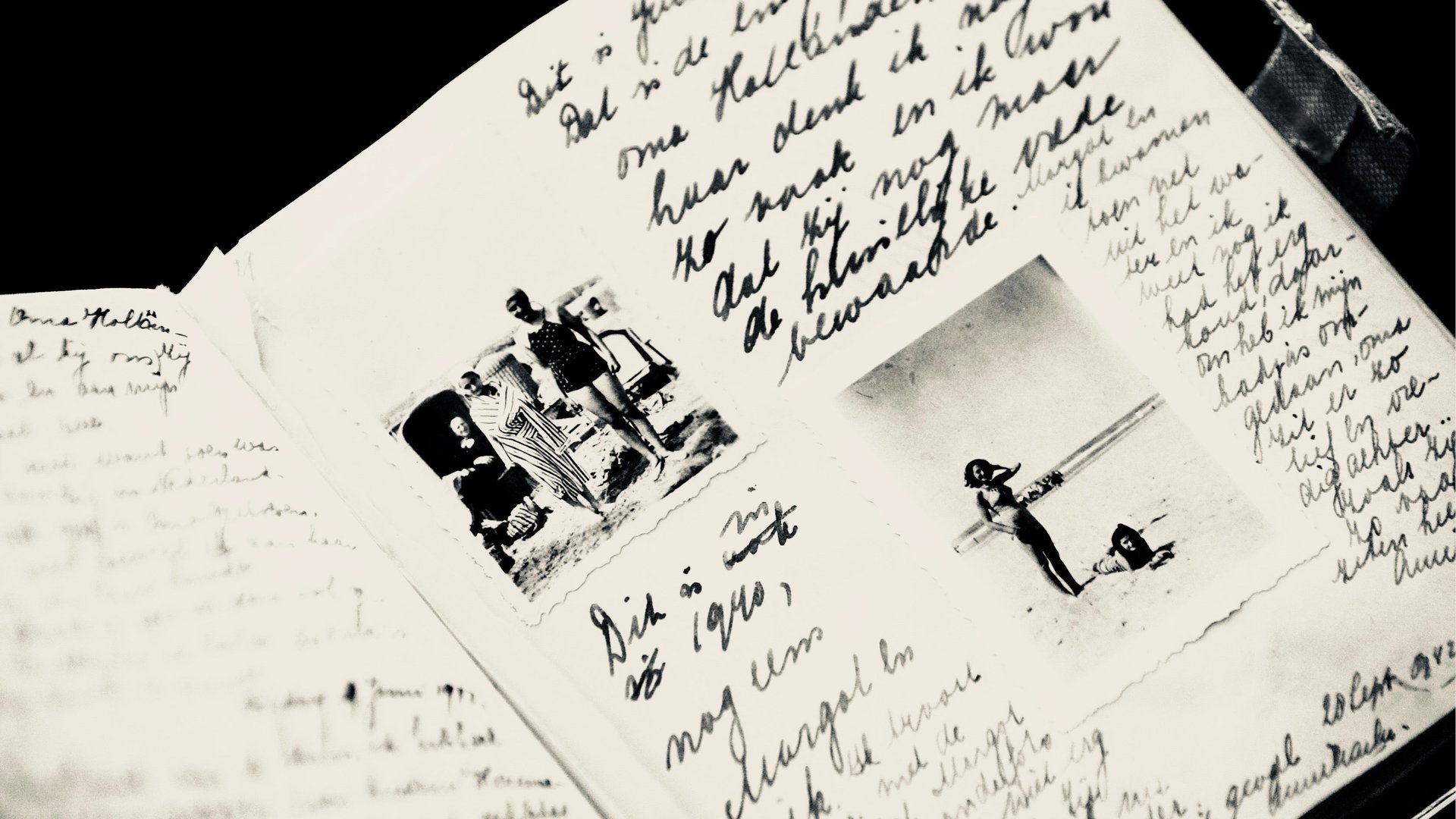

It’s true that some journals have had a lasting literary or historical impact, like the erotic diaries of Anais Nin or the diary of Anne Frank, an important record of a Dutch Jewish teen in hiding during World War II. Most personal records don’t endure, however. And as Quartzy’s Thu-Huong Ha explains, Frank actually wrote her now-famous work with an eye to publication. After hearing a Dutch politician on the radio say he planned to collect individuals’ accounts of Germany’s occupation of the Netherlands during the war, she revised and edited her personal journal.

Frank’s record then went from journaling to journalism, taking on a different quality. She didn’t want us to know her every thought—as evidenced by the May 15 revelation that taped pages in her diary, previously hidden from view, contained dirty jokes and notes on sex education and prostitution.

Frank’s revisions and hidden pages reveal more than her editorial process. They also show why the rest of us should toss all our journals, trashing the books we fill with precious feels after some time has passed. Journals aren’t written for mass consumption; they are therapeutic. Keeping them around for too long only weighs us down.

Why a diary

Filling journals is a healthy exercise that puts us in touch with our emotions and allows us to freely express ourselves. TOMS founder Blake Mycoskie began journaling when he was 15. Two-and-a-half decades later, he still journals at least once a day, and swears it’s key to his business success. “It became a form of therapy for me as an early entrepreneur, when things were really tough,” he said in 2017 on Fear{less} with Tim Ferriss.

Keeping a diary helped Mycoskie deal with his fear of failure when he needed to seem confident to others. “So then at night I could be scribbling about how concerned I was,” he explained.

Some therapists, like Susan Borkin, author of The Healing Power of Writing: A Therapist’s Guide to Using Journaling With Clients, even encourage clients to journal to improve their ability to express themselves during sessions. Keeping a personal record helps people to alleviate their anxiety, face fears, set goals, and feel more free.

Writing your thoughts and feelings down is liberating. You can tell the pages what you won’t say to anyone else. Get it all off your chest—make those dirty jokes, wonder about weird stuff, contemplate difficult victories, complain about pain, describe daily trials and tribulations, and lament the state of the world. Do it in a diary so the rest of society doesn’t have to deal with just how petty, miserable, and insecure you really are, and—most importantly—so that you don’t become a prisoner to those emotions.

Journaling also offers some of the same benefits as meditation, refining your relationship to the mind. It’s an opportunity to observe thoughts and feelings, watch them arise, and then let them go. Just as a meditator is taught not to judge thinking, but to note its qualities—how thoughts are constant and constantly shifting—a diary writer can become fluent in the language of contemplation.

Basically, this is navel-gazing for good. Learning to recognize the fleeting nature of our thoughts leads meditators and diary writers alike to the inevitable conclusion that not everything they think is important or permanent, nor do their fears and anxieties have to come true. This can help make a person more discerning about the reactions they express when interacting with others, and more effective in the world. Writing worries away has been proven to boost exam performance, for example. And keeping a dream log seems to help people find creative solutions.

Plus, writing by hand is soothing. It engages the brain in a way that typing on a computer cannot. Connecting pen to paper, filling pages, can provide inner peace.

Author Julia Cameron’s 1992 book on creativity The Artist’s Way has convinced many to write “Morning Pages.” Every day, people all over the world scribble 750 handwritten words before they do anything else (except, maybe, make coffee). Cameron developed the ritual when she was suffering from writer’s block. She says that Morning Pages “provoke, clarify, comfort, cajole, prioritize and synchronize the day at hand.”

Practice and detachment

Journaling is also good writing practice. As a journaling journalist, I believe my ability to formulate sentences professionally stems from efforts that began when I was a child scrawling emotions in books with blank pages.

But I’ve filled a lot of books over the years, too many to count. And if I kept them all, they’d weigh me down, literally and figuratively. So I don’t do it.

It used to seem important to have a record of my life, in case I might want to refer back to it years later. Experience has shown me that memory’s a friendly editor, however, and looking back at a diary can be embarrassing (as Anne Frank would no doubt agree if she were alive to protest the publication of her hidden pages).

It now seems to me that journals are for filling, but not really for reading. So, months or years after a book’s full, it’s tossed. The trashing process has become more rapid over the years. It’s very clear to me now that there’s more where that came from—more words, more feels.

That final act, tossing the journal, is painful but liberating. Letting go is a Zen exercise. It’s practice in detachment, forcing me to face facts, the simultaneous truths that everything matters and yet, ultimately, nothing does. Shit happens. We keep going. Tomorrow there will be more news.