Venezuela’s election was a sham, but it might just help keep chavismo afloat

Venezuelans have been buffeted by hyperinflation and widespread hunger. The reelection of president Nicolás Maduro on Sunday won’t change that.

Venezuelans have been buffeted by hyperinflation and widespread hunger. The reelection of president Nicolás Maduro on Sunday won’t change that.

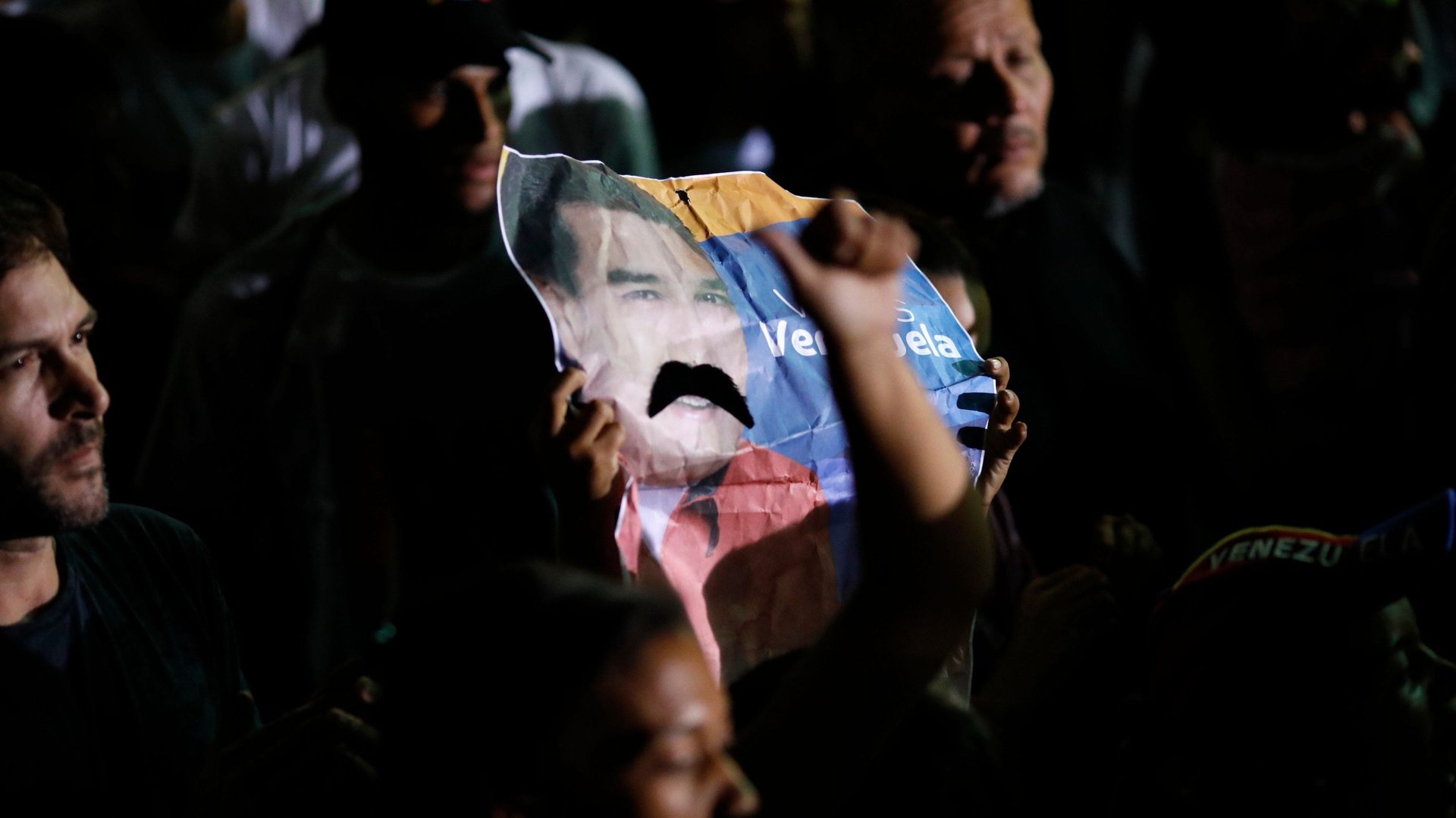

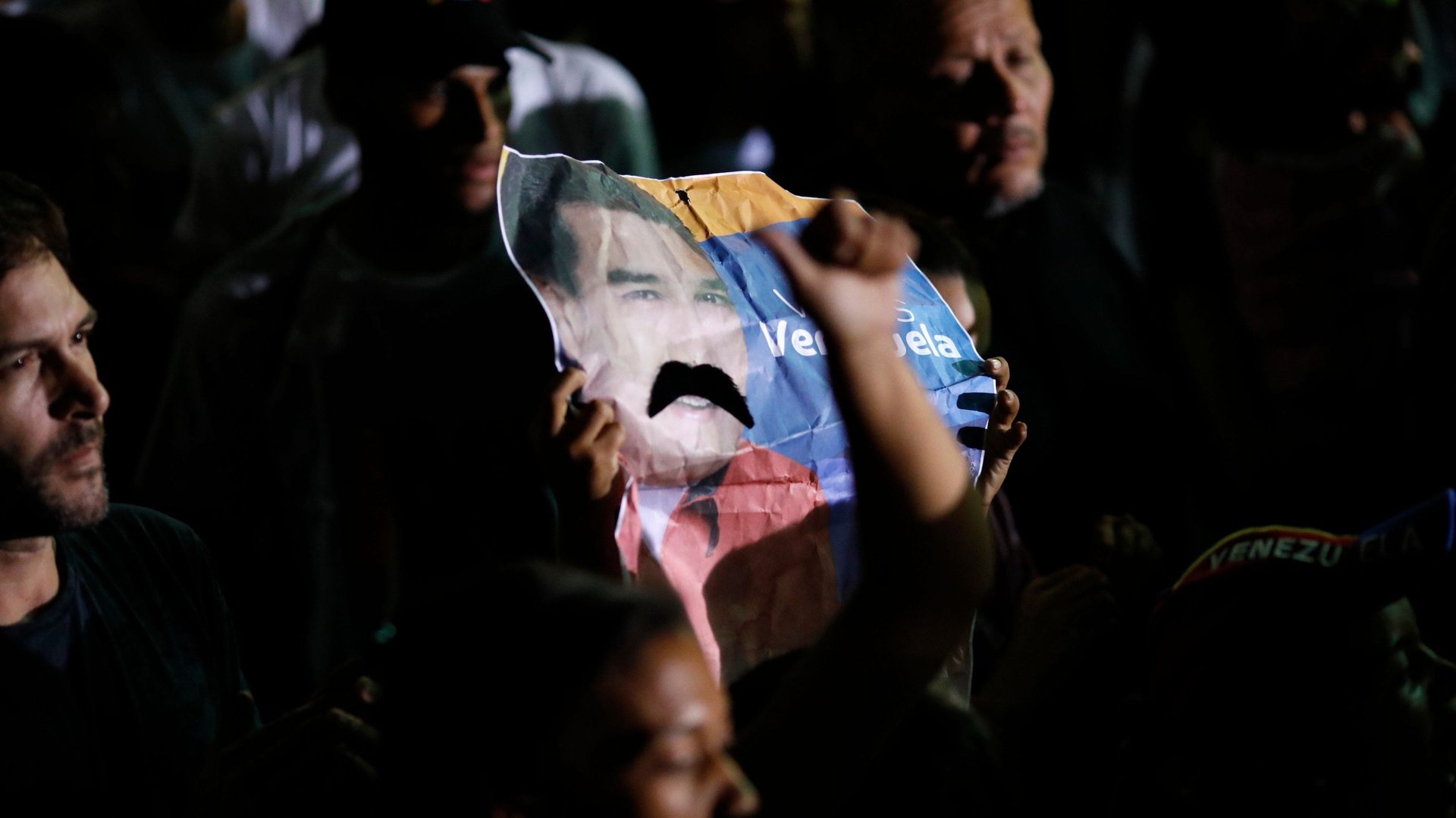

The vote, which has been called a sham by the opposition, several countries, and analysts, was Maduro’s strategy to maintain power amid flagging support. The results show he’s not getting any more popular—turnout was historically low, even by official statistics.

At the center of Venezuela’s woes are its oil reserves, the largest in the world. For the past two decades, they’ve enabled Maduro, and his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, to ignore simple economic principles while running the country. It’s a mistake that has tripped other Venezuelan governments as well. When oil prices are high, they overspend; when they collapse, they find themselves out of cash and mired in debt.

Soaring oil prices during the Chávez regime fueled his populist agenda, which consisted of social programs for the poor and punishing measures for private enterprise. Expropriations, along with price and currency controls, have decimated the country’s industrial and agriculture sectors.

Maduro has largely kept Chávez’s policies even as oil prices dropped. So now Venezuela is both out of money and a way to produce what it needs. It’s also got massive debt, some of which it’s already defaulted on.

Overhauling the economy would require painful measures that Maduro has been unwilling to make. At the same time, he seems committed to populist spending, even abroad: To continue supplying oil to Cuba, a practice started by Chávez to foster cooperation with a fellow socialist regime, Venezuela has been buying crude at a loss, Reuters reported last week.

It’s hard to imagine how conditions in Venezuela could deteriorate further. By this point, many companies, both local and foreign, have closed their doors. Six more years of Maduro would make it harder for the remaining ones to keep operating. Cereal giant Kellog pulled out of Venezuela last week because of the country’s “economic and social deterioration.”

Venezuela’s oil industry, too, is in trouble. The government’s mismanagement of state oil company PDVSA has resulted in a drop in production. It’s the kind of damage that’s not easily revertible. Venezuela’s cadre of oil professionals is thin; many left the country years ago. The country’s oil infrastructure is creaky due to a lack of investment and imported raw materials and parts.

After the controversial presidential election, the country now also faces potential US sanctions on its oil exports.

Ironically, Maduro’s rundown of PDVSA and his election’s irregularities may help keep chavismo afloat by reducing global oil supplies and pushing up prices. The higher prices would help offset PDVSA’s declining fortunes, at least in part. That could buy Maduro some more time in power.