The satellite images that exposed Iran’s secret rocket program

Poker players have a tell. So did the late Iranian General Hassan Tehrani Moghaddam: He liked his buildings painted aquamarine.

Poker players have a tell. So did the late Iranian General Hassan Tehrani Moghaddam: He liked his buildings painted aquamarine.

Earlier this year, weapons researcher Fabian Hinz was looking through Iranian media accounts of Moghaddam, who led the country’s rocket program. The general died in an explosion at a test facility in 2011, but in one picture taken shortly beforehand, Hinz told Quartz he spotted a box marked for delivery to Shahrud, a town in northern Iran.

Poring through satellite imagery provided by the earth-imaging company Planet, Hinz and his colleagues at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies found tell-tale blue roofs in the desert. Moghaddam had ordered another rocket facility painted the same color because of his passionate fandom for the Iranian soccer team Esteghlal F.C., whose players sport blue uniforms. Researchers had suspected the buildings near Shahrud were connected to a rocket program, and this quirk helped confirm their suspicions.

The color wasn’t just a legacy; the rocket lab they had discovered was active. Their findings, first reported in the New York Times, suggest Iran has been building rockets that are far more powerful than it has previously admitted.

“We started going back to see if, when Moghaddam died, did the program stop? Had they given up on this entirely?” David Schmerler, one of the researchers, told Quartz. “They started testing, clearly the program’s not dead.”

They were able to conclude this because Planet’s flock of small earth imaging satellites repeatedly survey the entire earth daily. Analysts looked back at historic data collected by the company and saw the facility expand over time. You can see new buildings popping up between 2015 and 2018 in this juxtaposition:

One sign this is a rocket facility are the earthen berms around the buildings, designed to contain explosives in the event of an accident. Those berms were missing at the facility where Moghaddam was killed.

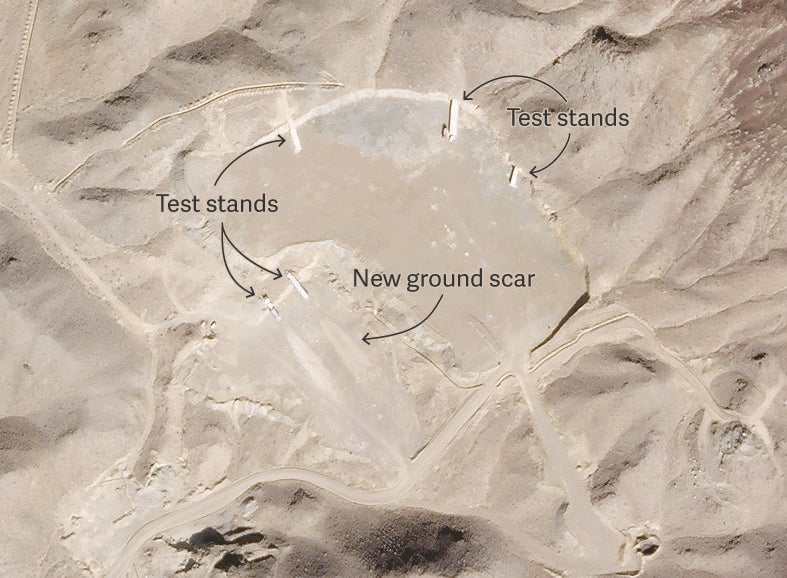

Nearby, the researchers hit pay-dirt, spotting a site used to test powerful rocket engines, a fairly definitive proof of on-going rocket development. The explosive force required to loft something across the globe at supersonic speeds can’t be demonstrated indoors, and a characteristic of the rocket industry are facilities in fairly remote areas where explosions won’t endanger the public.

Particularly important are the marks created on the desert floor by the red-hot exhaust of the rockets, which shows that the Iranians are actually firing the booster. The analysts suspect the two scars above were created by tests in 2017 and 2016.

What might these tests look like closer up? Here is a video of the US company Orbital ATK testing a rocket booster for NASA’s Space Launch System. This booster is one of the largest ever built, but the principles behind it are the same:

Solid rocket boosters are simpler than liquid-fueled rocket engines, but their simplicity also makes them more reliable and faster to deploy, a key consideration for missiles that are often intended to be hidden and then launched on short notice on a pre-set flight plan. The Middlebury researchers believe the rocket motors could provide enough thrust for a missile that could cross between continents, slightly less powerful than the US Minuteman III ICBM, which can carry nuclear weapons.

Just yesterday, Planet’s satellites snapped a new image that show Iranian workers paving roads at the site with asphalt. “I can see vehicles on the road, which parts have been paved, which parts haven’t,” Schmerler told Quartz. “They may be paving while this image was taken. You can’t get this imagery anywhere.”

The development of missiles, including those that could carry nuclear weapons, wasn’t prohibited by the deal reached by Iran with Europe, China, Russia and the US to halt the country’s nuclear weapons program in 2015. This exception was one reason president Donald Trump pulled the US out of the deal, leaving its future in jeopardy, though non-proliferation experts say it is far more important to prevent the development of nuclear weapons, a bigger technical challenge.

This new evidence suggests that Iran did not stop developing rocket technology while the deal was in effect. Iranian diplomats did not respond to requests for comment, but the country’s leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, has said that Iran will not make missiles that could fly more than 2,000 kilometers (1,242 miles). The rocket motors on these test stands would provide the power to exceed this limit.

There is significant uncertainty about the pace of this program and what its results could be. Once operational, the boosters could be used to launch conventional explosive weapons, or satellites into space, or nuclear weapons. The only certainty is that with a diplomatic process in shambles, Iran has a freer hand to pursue all possibilities.