The Hong Kong stock exchange on Beijing’s influence and staying relevant after Alibaba

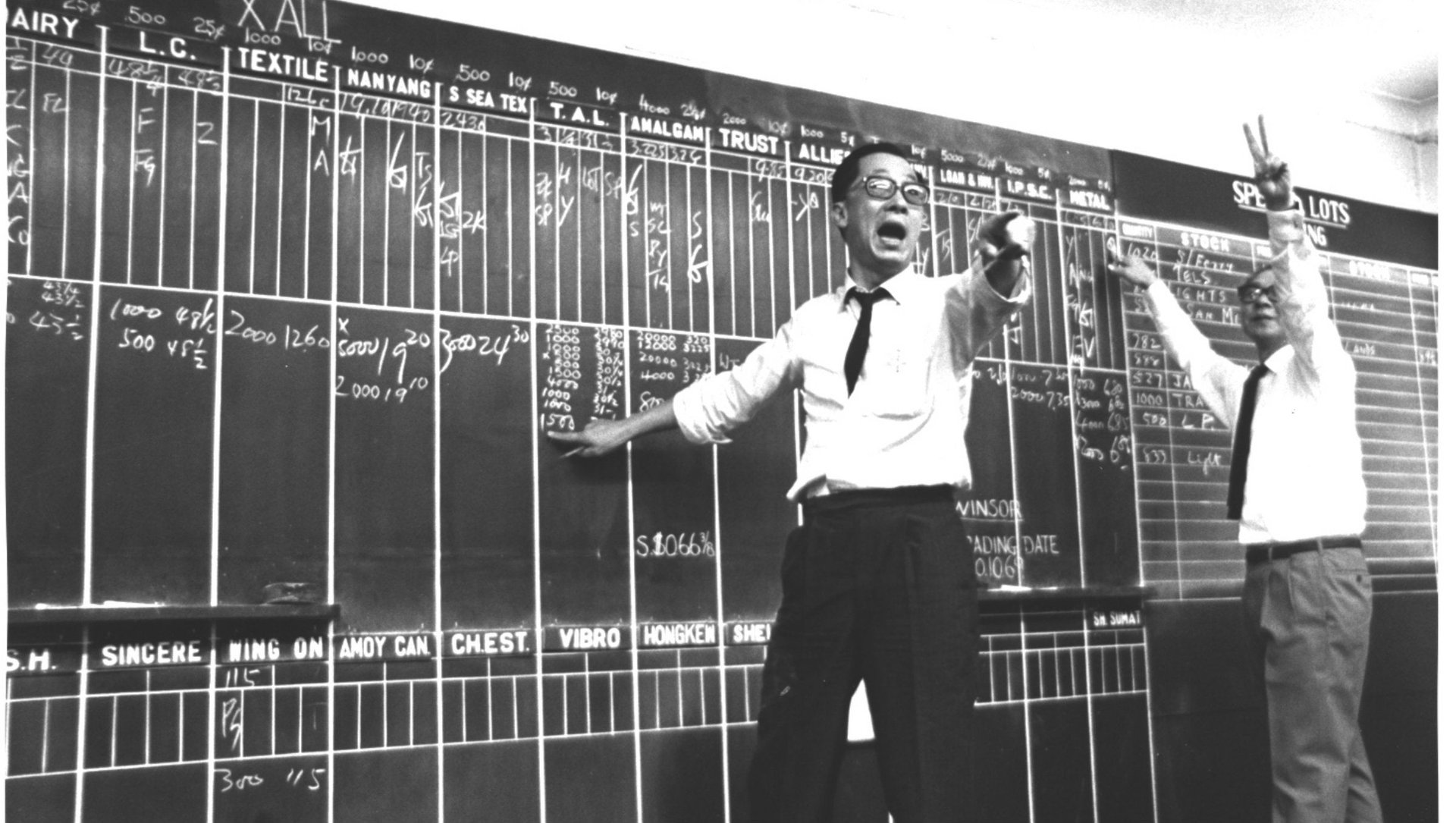

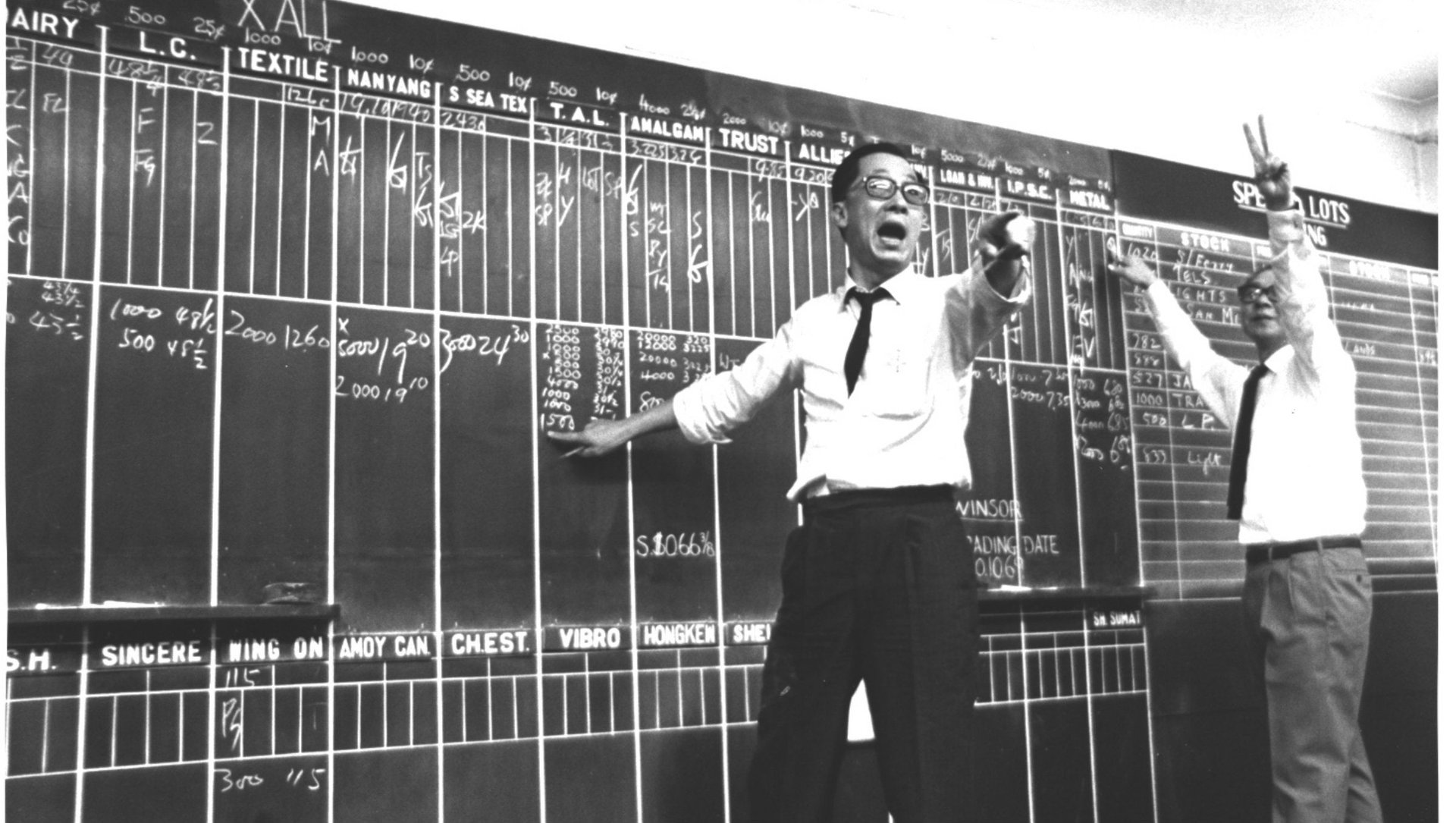

Stocks have been traded in Hong Kong since the 1890s, but when China’s hottest e-commerce company, Alibaba, decided recently to take the biggest technology IPO since Facebook elsewhere, it raised tough questions about the future of a city that has long been considered the financial gateway to China, and the relevance of its stock exchange.

Stocks have been traded in Hong Kong since the 1890s, but when China’s hottest e-commerce company, Alibaba, decided recently to take the biggest technology IPO since Facebook elsewhere, it raised tough questions about the future of a city that has long been considered the financial gateway to China, and the relevance of its stock exchange.

Hong Kong faces increasing competition to match foreign money with Chinese companies from around the world, including new financial initiatives from mainland China. Hong Kong was unwilling to bend its current listing rules to accommodate Alibaba’s management, which wants perpetual control of the company’s board even after it goes public.

Now Alibaba’s listing plans, expected to raise over $10 billion, may be punted into next year, anonymous sources told Marketwatch this weekend, and the company is still choosing between Shanghai and New York, signaling that the Alibaba listing fight is far from over. So far, the drama has played out with little input from Chinese officials. China’s state-run media, which often broadcasts the edicts and concerns of Beijing in news reports, has been nearly silent on the issue, except for reports on the verbal sparring.

While the Hong Kong exchange has been lauded for sticking to is principles, Alibaba’s biggest investors say they have no problems with the e-commerce company’s demands, leaving financial professionals in the city wondering if regulators and officials here are seeing the big picture. It didn’t help that Alibaba took a few parting shots at the exchange on its way out, saying “The question Hong Kong must address is whether it is ready to look forward as the rest of the world passes it by.”

Since then, China’s much-hyped Shanghai Free Trade Zone has opened, highlighting new challenges for Hong Kong. Most agree the zone does not present any direct competition right now, but it might in the future—foreign companies registered in the zone will be able to issue renminbi denominated bonds, for example and Shanghai hopes to set up an oil-trading platform.

How Hong Kong does, and should, interact with Chinese companies is a discussion with a long history. When Chinese mainland companies began listing on the Hong Kong Exchange as “H shares,” (Tsingtao Brewery was the very first in 1993), the exchange and Mainland officials debated whether Mainland companies should have their own, less stringent, listing standards, or comply with Hong Kong’s “higher standards,” as Hong Kong’s prolific chief executive Charles Li wrote in a recent blog post. Hong Kong won, setting “off a wave of Mainland company listings in Hong Kong,” he said, and driving “the long-term prosperity of the Hong Kong market.”

Quartz submitted questions to parent company Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (referred to below as HKEx), before and after Alibaba said publicly it would not list in Hong Kong. Answers came from its corporate communications department via e-mail from staff member Scott Sapp.

How concerned is the exchange about competition from overseas exchanges and the growth of mainland initiatives like the Shanghai Free Trade Zone?

The HKEx has been competing with other exchanges and alternative trading platforms all along.

We believe the Shanghai free-trade zone will benefit Hong Kong overall because it demonstrates that Mainland China is speeding up its liberalization. Hong Kong has benefited from Mainland China’s opening up and HKEx believes an even more open China will increase opportunities for everyone, including Hong Kong.

We will continue to invest in its infrastructure and people to maintain its competitiveness. The exchange reviews its rules and operations periodically and adjusts them when necessary.

Specifically, we have introduced a framework for listing of RMB-trading securities on the Stock Exchange, rolled out RMB currency futures and are developing a market data hub on the Mainland.

The US$380 million HKEx Orion program of new platforms and facilities was rolled out for the securities market last week. We introduced after-hours futures trading of Hang Seng Index futures and H-shares index futures in April.

We’re exploring new London Metal Exchange products, including Asia-related products, and building a clearing house for the LME that will be introduced next year to provide direct clearing services to the market. And we’re preparing to open an over-the-counter clearing house in Hong Kong for derivatives.

How would executives from HKEx characterize their relationship with officials in Beijing who are tasked with China’s financial growth? How is this relationship changing over time?

As Charles Li said in one of his blogs, “The world wants to come to China, and China wants just as much to come out to the world. Hong Kong is right at the center of this momentous trend and our success tomorrow depends on our finding the right solution for both sides today.”

HKEx’s general approach is to propose things it thinks would be mutually beneficial.

HKEx and its subsidiaries have had good communication with the Mainland authorities for many years. For example, the first H-share listings 20 years ago required a lot of communication between the Stock Exchange, Hong Kong regulators, Mainland regulators and Mainland authorities.

With respect to suggestions HKEx might report to the Mainland or act on its behalf, they are incorrect. HKEx maintains good communication with the Mainland authorities in the course of its business and market development, but the “one country two systems” arrangement ensures that Hong Kong’s financial market regulation is independent from that of the Mainland. As a market operator in Hong Kong, HKEx is subject to the regulation of the SFC and the law of Hong Kong.

Can you tell us how the London Metal Exchange deal was done, for example, and interaction with Beijing during that time?

The LME acquisition was initiated by HKEx.

There was a purely internal catalyst for the acquisition, perhaps best stated in our current strategic plan: “As the Mainland’s growth continues to evolve, we expect the Mainland’s needs to shift increasingly from capital formation to investment diversification and risk management across all asset classes, reflecting the country’s transformation from an importer of capital to an exporter of capital. A presence in multiple asset classes will position us to serve the Mainland economy across a broad front during this evolution.”

HKEx is a commercial enterprise with a widely diversified base of retail and institutional investors, and the LME acquisition was about pursuing HKEx’s commercial interests.

What is the HKSE’s on the record response to critics who complain your technology is slow, with trades taking minutes to complete some times?

HKEx proactively monitors the performance of all its markets. Should any of its exchange participants find slow responses on their orders or trades, they can get in touch with HKEx with the details and HKEx will investigate and report back. Capacity management and planning are carried out regularly and systems are upgraded if necessary to ensure they can handle increases in market activity.

As a result of the an upgrade in December 2011, HKEx’s securities trading system’s processing capacity was increased about 10-fold to 30,000 orders per second.

There are also criticisms about how stock closing prices are derived—a mean of five last trades.

HKEx continues to look at potential market microstructure enhancement measures but does not have any plans for changes at this point. Any future proposals in this area would be put forward for public consultation before there were any decisions on possible implementation.

How important is it for HK that Alibaba list here?

It is HKEx’s general policy not to comment on individual companies, individuals, or cases.

Answers have been lightly edited and condensed.