Clarence Thomas compared the Supreme Court’s gay wedding cake case to cross-burning

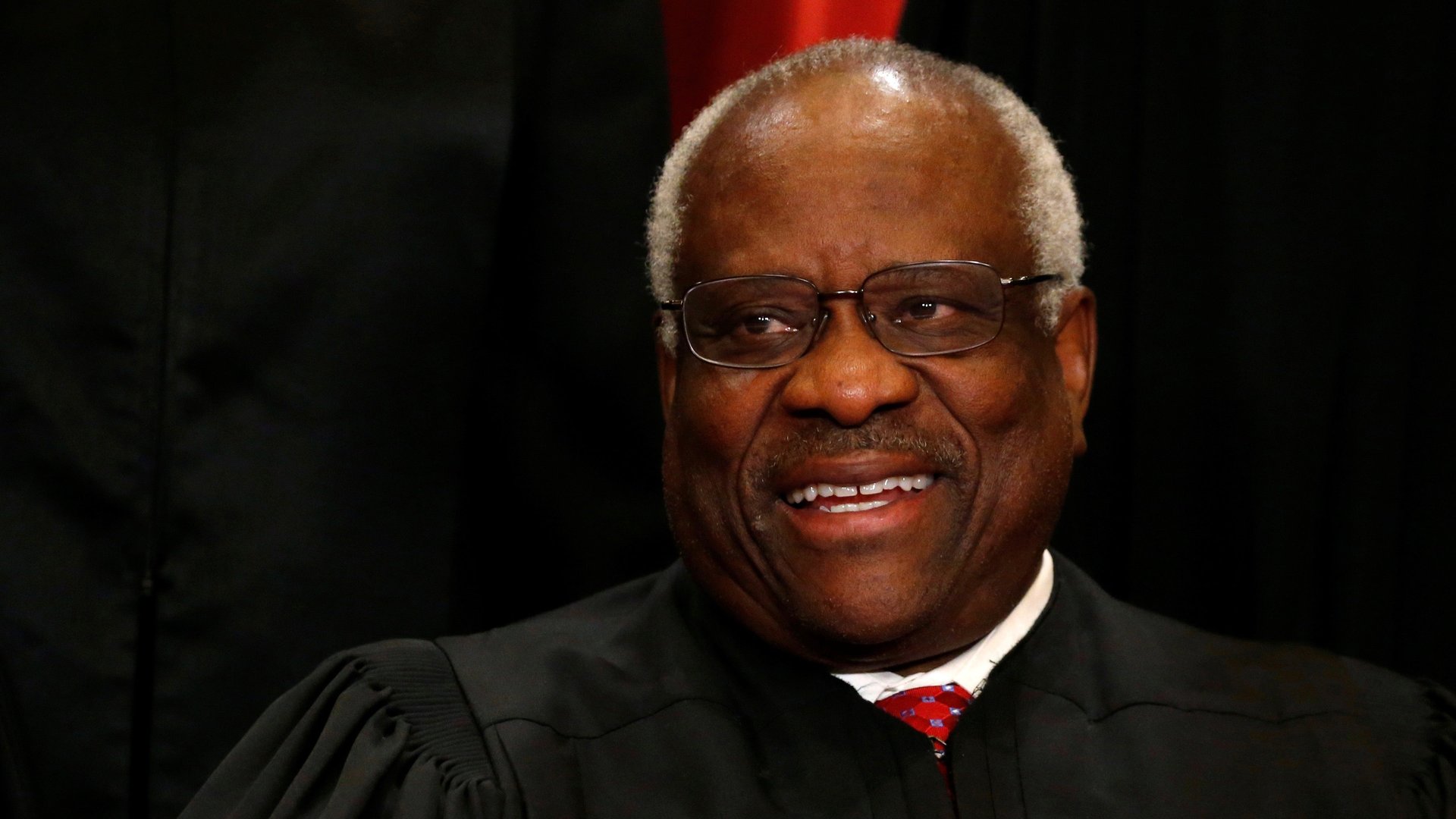

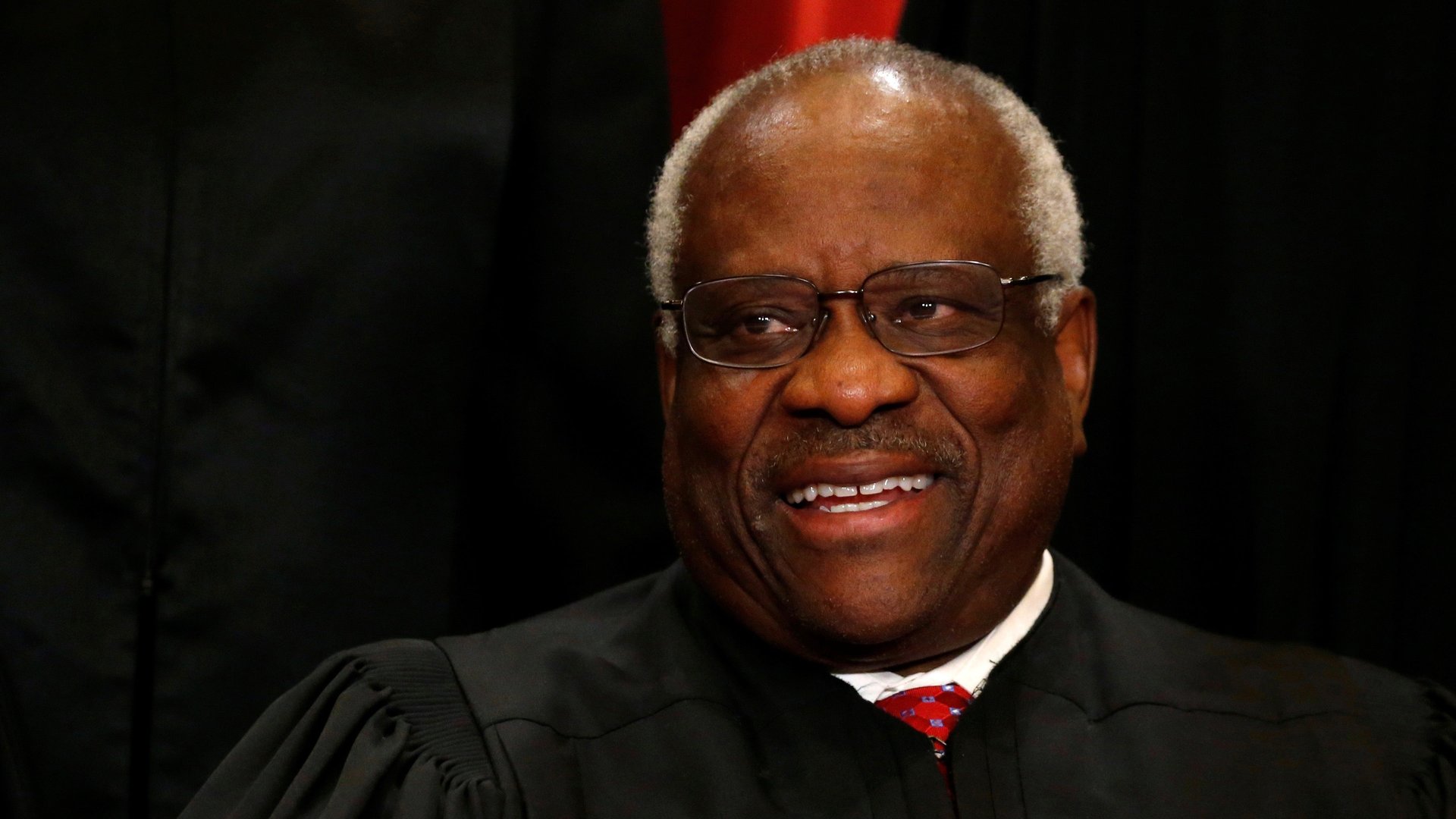

US Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas is enigmatic. The court’s mostly silent justice speaks so little at oral arguments that his few utterances get serious attention.

US Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas is enigmatic. The court’s mostly silent justice speaks so little at oral arguments that his few utterances get serious attention.

In 2002, for example, during arguments in Virginia v. Black—a case about the constitutionality of a statute banning cross-burning—he stunned justices with a two-minute soliloquy on the country’s racist history. Then, in a dissenting opinion, he argued that cross-burning was never free speech, and should never be considered as such. Cross-burning, he argued, is ”unlike any symbol in our society…There’s no other purpose to the cross, no communication, no particular message. It was intended to cause fear and to terrorize a population.”

Today, Thomas’s scathing concurrence in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission(pdf) recalls that case.

Thomas reminds his colleagues that the Supreme Court has been pretty tolerant of intolerance in the past, when it was against African-Americans, despite their robust defense of gay rights and their concern for the “dignity” of homosexuals in the cakeshop case. If cross-burning is debated as free speech worthy of constitutional protection, he reasons, surely refusing to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding is too.

The court’s only African-American justice is sharply critical of past rulings that allowed “racist, demeaning and even threatening” speech and conduct towards blacks under the guise of First Amendment protections. He argues that Jack Phillips’ refusal to bake for a gay marriage in 2012 was, by comparison, very mild and well within the territory of protected speech, writing:

Concerns about “dignity” and “stigma” did not carry the day when this Court affirmed the right of white supremacists to burn a 25-foot cross [in]Virginia v. Black; conduct a rally on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday [in]Forsyth County v. Nationalist Movement; or circulate a film featuring hooded Klan members who were brandishing weapons and threatening to “‘Bury the niggers,’” [in]Brandenburg v. Ohio.

Thomas also points out that the most offensive notions are actually those that demand the most constitutional protection. After all, it’s no big deal to protect speech that everyone agrees is fine and ideas that most people support. But the law is there to ensure that unpopular opinions can be expressed, he argues, especially if they’re fundamentally distasteful to many.

For that reason, Thomas believes that Jack Phillips’ refusal to produce a cake for a union he claims offends his faith deserves the same discussion as cross-burning and racist parades. The fact that same-sex marriage has since been legalized in no way diminishes the issue, he says, nor does it make everyone who doesn’t believe in such unions “bigoted,” or require them to remain silent, he contends.

“This Court is not an authority on matters of conscience, and its decisions can (and often should) be criticized,” Thomas writes. “The First Amendment gives individuals the right to disagree about the […]the morality of same-sex marriage.” He warns that legalization of same-sex marriage shouldn’t be “used to stamp out every vestige of dissent and vilify Americans who are unwilling to assent to the new orthodoxy.”