Russia loves football. History explains why it’s so bad at it

A scene in the film Playing the Victim (2007) epitomizes Russians’ pained relationship with their national sport.

A scene in the film Playing the Victim (2007) epitomizes Russians’ pained relationship with their national sport.

A gnarled police detective, infuriated by a case he’s working on and the incompetent colleagues surrounding him, suffers a tearful, expletive-filled breakdown. After smashing up a restaurant, berating the staff and ranting about the youth of today’s Russia, he sits with his head in his hands and cries: “Twenty-six years! For twenty-six years our football team have been fucking me over. Before, ok, there were some successes; they got to a few finals. But now, fuck, they’re not even in the World Cup. It’s a fucking shitshow.”

The scene—in a film that has nothing to do with football—has become “folklore” among fans of the Sbornaya, the national team, says Andrei Apostolov, an adjunct lecturer at the Russian State Institute of Cinematography who writes about the role of sport in Russian arts. “Football is our most beloved game, but it’s also a constant Russian tragedy,” he says.

Suitably humble beginnings

The match that spawned top-flight football in Russia was fittingly inauspicious. In 1936, with no professional football in the Soviet Union, a select team of Moscow’s best players travelled to Paris and suffered a brave 2–1 loss against Racing Club de France. Despite the defeat, they put together a good enough show to persuade Soviet authorities to start a professional league for the already deeply popular sport, says Robert Edelman, a Russian sports historian at the University of California, San Diego.

Although widely considered the country’s favorite sport, it was never the authorities’ main love. In the early Soviet period, the intelligentsia preferred tennis and track, Edelman says. One large intellectual movement considered football too “bourgeois” and even wanted to change its rules or replace it with newly invented games, though it’s not clear that any found significant popularity. Stalin himself “had no interest whatsoever in [football],” Edelman says. The neglect from the Kremlin continued after World War Two, with the Soviet Union showing extraordinary prowess at the Olympics, but never achieving the football dominance that a superpower of its size deserved.

Those failures actually made football more in tune with Soviet society, Edelman says. “Football is a better reflection [than the Olympics] of what life in the Soviet Union was really like, which is something less than perfect,” says Edelman, author of two books on Russian sports history. “Things didn’t work all that well, and obviously in football things didn’t work all that well…it’s not the kind of thing you can control as easily as the best results in fencing or whatever.”

Inexplicable popularity

And, yet, despite reams of Olympic gold medals and a period of Soviet dominance at ice hockey, football has stayed at the center of the country’s sporting imagination—in a very Russian way. “In Russia, we turn everything into a tragedy. Maybe that’s why we don’t love hockey so much; because we’re quite good at it and it’s not so interesting,” Apostolov says. “[Football] creates a national inferiority complex—the country loves it but we still lose all the time.”

Central to the Sbornaya‘s failures, Apostolov argues, is the lack of any cohesive tradition of how to play the game. Where the Dutch play end-to-end “total football,” the English have big defenders and powerful strikers, and the Spanish can pass any team off the field, for Russia, “it’s not even clear what they’re playing,” Apostolov says. “It’s not that they play badly or lose, it’s just not clear what they’re doing.”

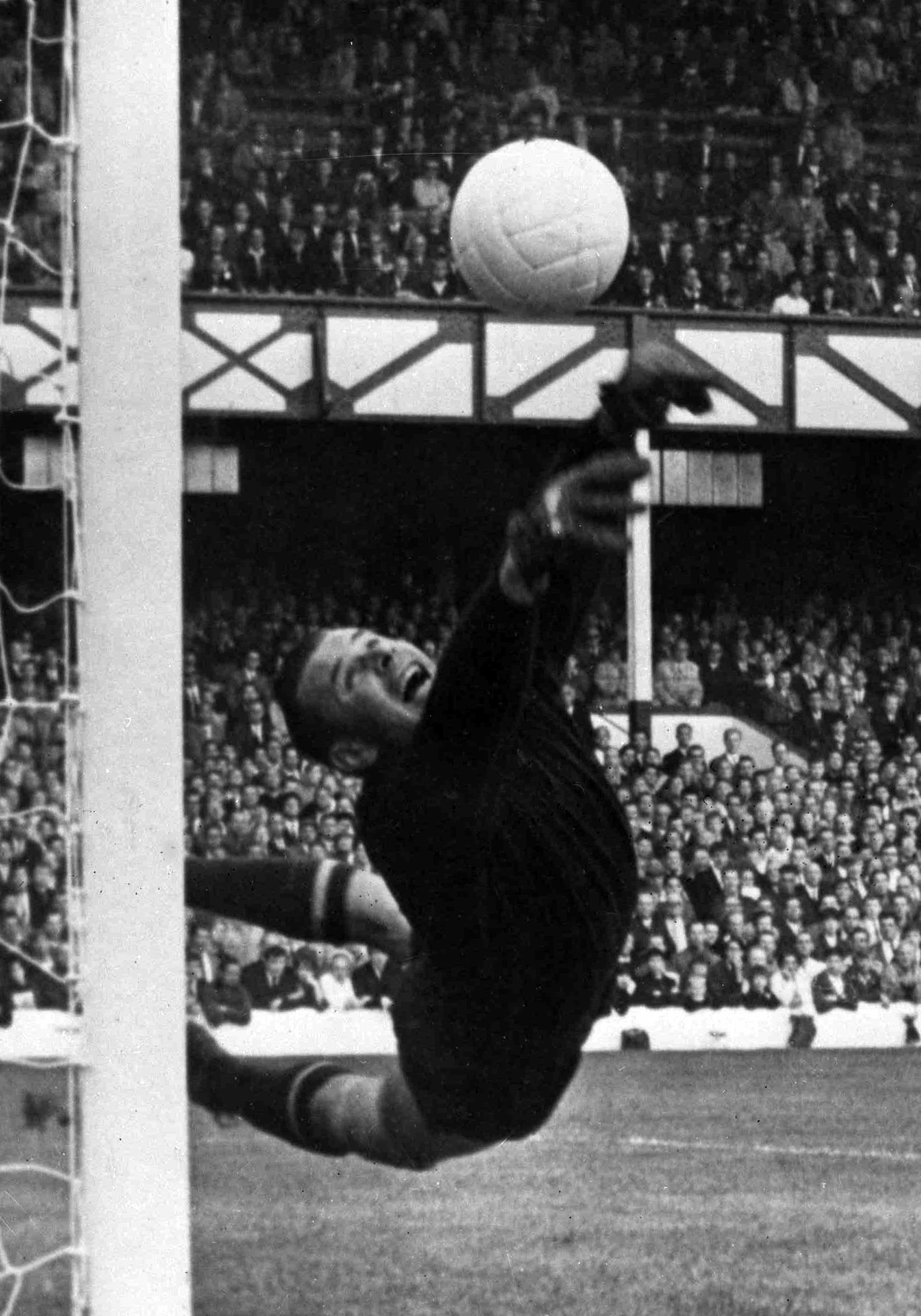

The one constant in Russia’s footballing identity, Apolstolov argues, has been the cult of the goalkeeper, who came to symbolize the defender of the gates against the capitalist enemy. The goalkeeper has been lauded in Russian culture as far back as the 1920s, where Yury Olesha’s classic novel Envy (1927) had a brilliant young goalie as the hero of its central football match against the capitalist Germans. Vladimir Nabokov followed suit five years later in his semi-autobiographical novel Glory, about exile in England, where the protagonist revels in his role as a goalkeeper while at Cambridge University. In the film The Goalkeeper, released just as the Soviet Union’s professional league began in 1936, a young man is picked from nowhere to glory as a goalie.

Out of this culture appeared Russia’s greatest ever player, Lev Yashin, a plucky black-capped hero, believed by many to be the best goalkeeper of all-time—despite, he claimed, drinking a shot of vodka before games to tone his muscles and smoking a cigarette to calm his nerves. He was lauded as a “revolution in football” in a poem by anti-Stalinist rebel poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, had works dedicated to him by national bard Vladimir Vysotsky and poet Robert Rozhdestvensky, and is at the center of the 2018 World Cup’s richly symbolic poster.

Today’s Russia team

The latest in the tradition of great Russian keepers is Igor Akinfeev, the team’s captain and one of its few world class players. He leads a troubled side into this World Cup, starting the tournament as its lowest ranked team. The country’s record since the end of the Soviet Union has been dismal: they’ve failed to qualify for three out of the six tournaments since 1991, and not made it out of the group stages when they have appeared. That’s a miserable run by any standard, but especially considering the Soviets thought their pre-1991 record of a semi-final and three quarter-finals was bad.

The theories for the decline are many. In splitting off from the other 15 Soviet Republics, the team lost many of its great talents, with 150 million fewer people to choose from. The once fiercely competitive all-Soviet league now became just the Russian league, functioning in a dire economy with no means to buy good foreign players. The 2000s saw the oil economy boom and a brief spurt of success as money was ploughed back into football. Two Russian clubs won the UEFA cup in quick succession and the national side reached the 2008 European championship semi-finals. The renaissance didn’t last long; Russia failed to qualify for the 2010 and 2014 World Cups.

Sergei Bondarenko, a football historian at Memorial NGO, believes Russia has hamstrung itself in two ways. One is a limit on the number of foreign players allowed in the domestic league, which started with every team being allowed a maximum of seven foreigners on the pitch in 2012, and was lowered to six in 2015. “[Now] you don’t really have to play very well to be in the team, so you don’t have to progress,” Bondarenko says. “Six years later, we have a very average team even with some quite good young players who play inside the country and make no progress from year to year.”

The other is a problem that plagues the country as a whole: corruption. “A lot of the guys who work in the sporting infrastructure are very far from being professionals, they’re more like friends or connected with the guys who are in power,” he says.

In the run-up to the country’s first home World Cup, Russians had become so pessimistic that striker Artyom Dzyuba made a plea that fans and journalists stop criticizing the team. “There’s a very negative atmosphere at the moment…the tournament hasn’t started and you’re already acting very aggressively,” he said at a press conference. “Right now I’m asking for us all to join together for our country.” Dzyuba helped ease the pressure in Russia’s first game of the tournament, scoring a goal in a 5-0 thrashing of an abysmal Saudi Arabia team.

Nonetheless, hopes aren’t high. “Of course, we can get out of the group—and we will be hugely beaten in the first round of the play-off. In a way, that will be great because it’s the first time since 1986 since the Russian or Soviet team got out of the group stage,” says Bondarenko. “But I don’t think will mean too much in a broad sense, because the problems are really deeper in the whole structure of football here.”