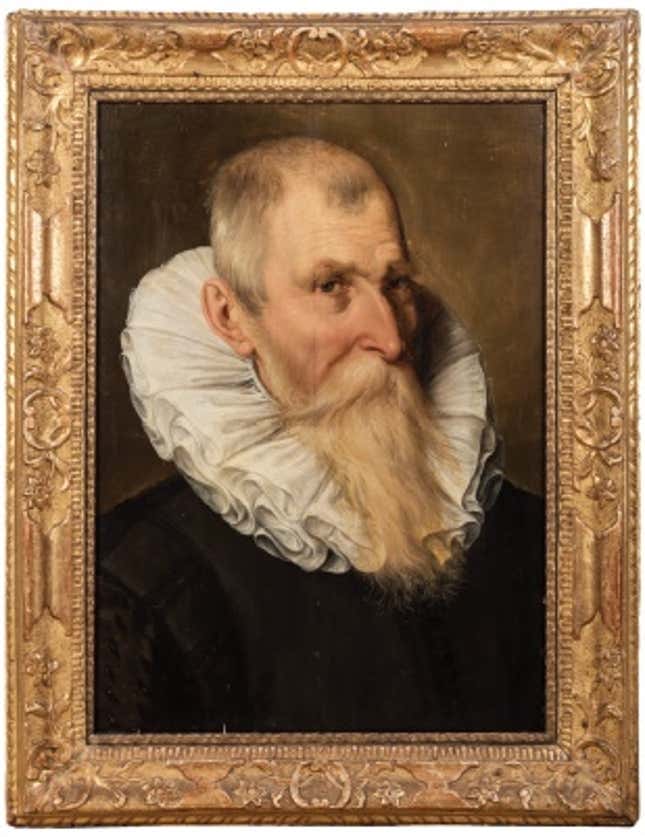

Smuggled out of Nazi Germany decades ago, the striking painting by one of Europe’s old masters has hung in a Johannesburg home without attracting undue attention for years. But this week, Sir Peter Paul Rubens’ Portrait of a Gentleman has resurfaced to much attention.

Baroque Old Master Rubens lived between 1577 and 1640 and was one of the most celebrated painters of 17th century Europe. The oldest known auction of the portrait was in 1740, and in the years since, the oil on oak panel painting has lived a storied life over two continents. The Flemish master is believed to have painted it between 1598 and 1609, and the picture of the unknown man has changed many hands and several countries.

By 1925, it belonged to a German-Jewish doctor who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Where other Jewish art collections were looted by Nazi soldiers, the doctor got out early after one of his patients warned him about how dire life would become for Jews in Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

The doctor, who will not be named, hid his art collection and other possessions with trusted patients until he was able to secure safe passage to South Africa. In Johannesburg he continued to practice and teach until his death, with the Rubens hanging on his walls.

Last year, the man’s family approached the Stephan Welz & Co auction house. It is now on silent auction until June 29, and expected to fetch between five and eight million rand ($370,000-$592,000), said Anton Welz, the gallery’s divisional head.

In the last few years, several masterpieces have been found hiding in plain sight. The iconic portrait by Nigerian painter Ben Enwonwu Tutu, missing for decades,was found in a London flat and sold for a record price earlier this year. In another London flat in 2015, Irma Stern’s Arab in Black was spotted “hanging in the kitchen covered in letters, postcards and bills.”

The oil painting by the famed mid-twentieth century South African artist sold for 842,500 pounds ($1.1 million) in 2015. The media interest these rediscovered paintings generate, however, obscures how rare it is to find a lost masterpiece—even in a London flat.

“Most people know what they’ve got,” Welz told Quartz. “It is interesting because there’s a story there but it’s an exception rather than the rule.”