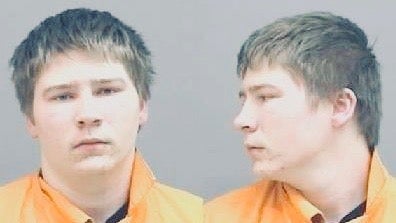

US Supreme Court rejects appeal of Brendan Dassey from Netflix’s “Making a Murderer”

The US Supreme Court has decided to not weigh in on the question of coerced confessions from juveniles with mental disabilities.

The US Supreme Court has decided to not weigh in on the question of coerced confessions from juveniles with mental disabilities.

The court rejected a petition for review (pdf) from Brendan Dassey—whose case was featured in the 2015 Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer—despite the show’s popularity and his impressive roster of advocates, including a who’s who of Washington DC lawyers. The court offers no explanation, only listing it today (June 25) among other denied petitions in its order list (pdf).

Dassey is serving a life sentence for murder, rape, and corpse mutilation, crimes he admitted to when he was 16. He has an IQ of 70 and linguistic difficulties. In 2005, after a series of interviews with police investigators—who pulled him out of school to talk, and seemed to be feeding him answers until they got the responses they wanted—he admitted to killing Teresa Halbach, a 25-year-old woman visiting his uncle, Steven Avery. There was no attorney or parent with Dassey during most of his meetings with police. No physical evidence linked him to the crime. After he confessed to murder, he asked to be taken back to classes.

In its petition for the high court’s review, Dassey’s counsel positioned him as a representative case. His attorneys noted that teenagers are overwhelmingly more susceptible to pressure from police to admit to crimes they have not committed. Pointing to statistics on coerced confessions from juveniles and people with mental disabilities, Dassey’s legal team argued that his case would provide an opportunity for the Supreme Court to reissue its guidance to state court judges on how to weigh the evidence when considering these kinds of confessions.

Judges are supposed to consider the “totality of the circumstances,” weighing factors like age and intelligence heavily. Dassey’s attorneys argue that the Wisconsin judge who allowed his statements to be used against him didn’t do that—instead, he weighed age and intelligence on par with arguably irrelevant factors, like the sofa Dassey sat on during questioning.

The American Psychological Association supported Dassey’s petition. The American Bar Association (ABA) argues on its website that coerced confessions from kids who can’t yet understand consequences and are eager to please authorities—and a similarly vulnerable group, people with limited intellectual abilities—is common. Dassey’s case seemed promising because of the publicity the Netflix documentary generated and because his confession was elicited under pressure despite him suffering from both vulnerabilities—youth and diminished intellectual capacity.

Juveniles, in particular, falsely confess “with startling frequency,” the ABA says. They are two to three times more likely to admit crimes they didn’t commit during interrogation than adults. A study of 340 exonerations found that 42% of juveniles had falsely confessed, compared with just 13% of adults. Meanwhile, the ABA reports, an experimental study found that a majority of youth complied with a request to sign a false confession “without uttering a single word of protest.”

In a statement, Laura Nirider of Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law Center of Wrongful Convictions of Youth, argues that children and teens are between three and four times more likely to falsely confess than adults: “It’s up to the courts to put an end to this. Now, more than ever, courts around the country must update their understandings of coercion in light of the newly understood problem of false confessions.”

Nirider notes that dozens of former prosecutors, national law-enforcement trainers, leading psychological experts, innocence projects, juvenile justice organizations, and law professors filed briefs in support of Dassey’s case. She says they “will continue to fight for Brendan and the many other children who have been wrongfully convicted due to the use of coercive interrogation tactics.”

Clarification: This story was updated to reflect the fact that the ABA did not support Dassey’s petition. Its website does discuss his case and provide data about the prevalence of false youth confessions, however.