How to come up with better ideas, according to scientists who developed a new theory of human evolution

A group of scientists have a new theory about how humanity came to be—and the story of how their theory came together is a lesson for the rest of us. It shows how breaking out of professional and ideological silos can lead to groundbreaking ideas.

A group of scientists have a new theory about how humanity came to be—and the story of how their theory came together is a lesson for the rest of us. It shows how breaking out of professional and ideological silos can lead to groundbreaking ideas.

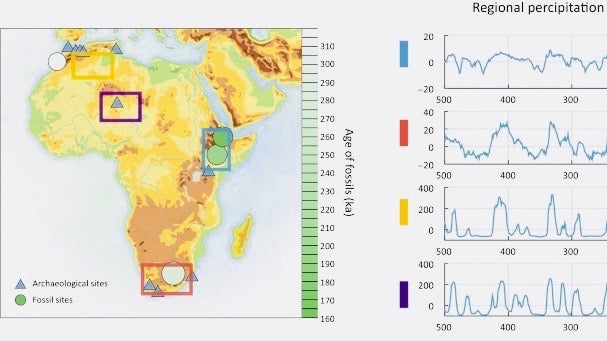

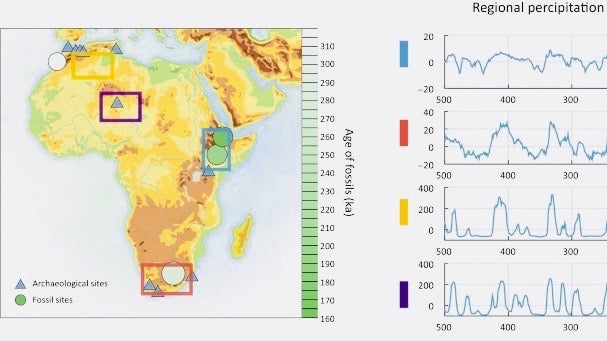

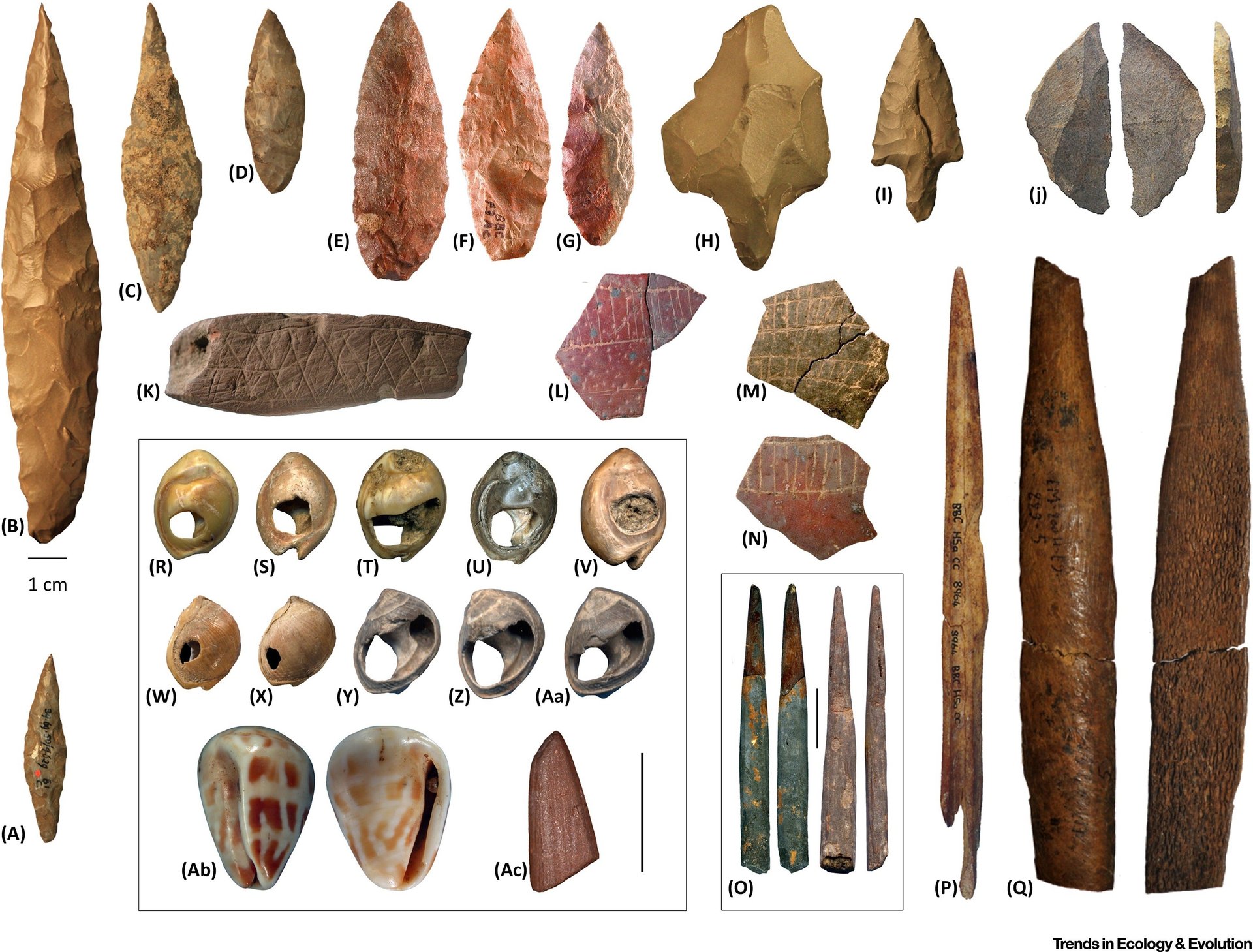

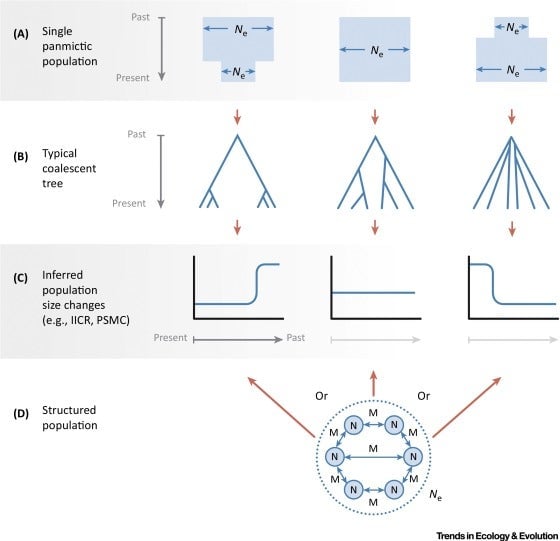

For years, the consensus has been that Homo sapiens emerged from one spot and one population in east Africa some 300,000 years ago. But according to a new paper in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution, we didn’t come from one place or population on the continent. Instead, lineage of Homo sapiens probably originated in Africa at least 500,000 years ago—evolving from interlinked groups across the entire swath of Africa toward contemporary human morphology over tens of thousand of years.

This slow and expansive change was influenced by ecological and genetic shifts, according to the authors. They say future work should acknowledge “multiregionalism” and the complexity of our African origins.

This complex new view of human evolution emerged from a sophisticated approach to research. The scientists who proposed this theory have different specialties and come from institutions around the world. They include archaeologists, anthropologists, biologists, geneticists, geographers, environmental scientists, and zoologists.

Once assembled, the interdisciplinary research team took a more nuanced approach to human evolution than usual. Instead of focusing on individual fossil finds—the shape of skulls, say—or specific tools found in a single place to tell humanity’s origin story, they looked at the big picture. The scientists pooled data from disparate studies and specialties to come up with a cohesive theory of humanity’s emergence that accounts for ecological changes and migration patterns, as well as bones and artifacts.

In other words, to come to their new view of evolution, they had to step outside the boundaries of their specific fields and collaborate. Here’s what they did to work together—and how you can do the same:

Recognize your blind spots

“Preventing bias was the key point,” lead researcher Eleanor Scerri, from the department of archeology at Oxford University, tells Quartz. Each of the disciplines represented in the research group has a particular culture, ways of thinking, various methodologies and data sources.

Separately, each discipline has come up with its own conclusions about human evolution. But together, they developed a holistic, rather than fractured, view, Scerri explains.

“We all felt strongly that moving forward had to involve breaking down barriers between disciplines, and beginning a respectful conversation about how circular bias can easily be constructed by cherry picking across different sources of data to match a narrative emanating from one [field],” she says. Scerri’s group was aware of the ways that any single scientific narrative can become dogma in a given field, which is difficult to challenge once entrenched. And that’s problematic for knowledge as whole. Scerri says, “We all wanted to confront the fact that last year’s inference can become this year’s orthodoxy, and that we didn’t necessarily agree about everything ourselves.”

Throw assumptions out the window

Basically, the team needed to put everything, including common assumptions in their fields, up for debate. That was the best way to resolve conflicting theories and develop a cohesive view of the various findings. So, the researchers met for three days and hashed out ideas head-to-head.

They didn’t make presentations as they would at a traditional scientific conference. Instead, they analyzed each other’s work and ideas, identifying both the problems and accomplishments.

“I think a particularly heartening feature of our group is that we started off from quite different positions, but managed to produce a coherent view that accounted for everyone’s positions. It felt like a perilous approach at first, but was ultimately incredibly rewarding,” Scerri says. “The scientific ideal really prevailed…There was a lot of camaraderie and good will, which was fantastic, despite the occasional disagreements some of us may have had.”

Get rid of jargon

To integrate the work of so many different scientists and put together all the different findings, the team had to develop a common language. “That usually involves carefully breaking down jargon and understanding at least the principles of different methods of analysis: what the data says, and what’s inference—an outcome of a particular model used and what that model’s assumptions and limitations are,” Scerri explains. “That’s a pretty big ask, but this is the direction of research, especially in fields like human origins where there are so much missing data.”

Since it’s difficult for a scientist to specialize in more than one field, researchers have to pool their knowledge and learn to talk across specialties. Otherwise, the conclusions that emerge about a finding are likely to be limited by individuals’ backgrounds, according to Scerri. “Understanding of findings tends to influenced by the models and paradigms we have in our heads, which tend to act as a filter to how we process new information,” she says.

Get comfortable with conflict

Bringing together people who disagree isn’t always easy but it leads to a deeper understanding of seemingly conflicting conclusions. As a team, the researchers weaved their different theories into a cohesive story that makes more sense and accounts for complexity. “It’s rarely the case that one person is wrong and the other is right,” says Scerri. “Insights from different models can help to shed light on the answers we look for…Perhaps we can say that nothing is really entirely new in science, it’s all about incremental steps and changing perspectives.”

With this latest paper, scientists have done just that, shifting our view on our African origins and upending the single human birthplace story.

But they are not dogmatic about the new narrative they created. “It’s important to remember that it’s ok to be wrong as long as it’s for the right reasons. We are probably all wrong to a degree,” Scerri says. In other words, just like humans evolved over time in a complex fashion, so does our scientific understanding. In due time, an even more sophisticated story will no doubt emerge. That doesn’t bother Scerri. ”The important thing is pushing new frontiers, questions and testing hypotheses, as this is of course how science progresses,” she says. “And we all contribute to that, we all stand on the shoulders of giants and all giants got some things wrong!”