Three theories about Trump’s plan to build an entire village in rural Scotland

Last month, the Trump Organization announced something strange: a plan to build an entire town in rural Scotland, with a kitsch design that blends American suburbia with Scottish oil country. The price was $200 million, but where the Trumps will get that cash is a mystery.

Last month, the Trump Organization announced something strange: a plan to build an entire town in rural Scotland, with a kitsch design that blends American suburbia with Scottish oil country. The price was $200 million, but where the Trumps will get that cash is a mystery.

It’s the latest in a string of Scottish investments which appear to make little business sense. The Trump Organization has already shelled out hundreds of millions on two golf courses in the country in the last 12 years, and both have performed terribly. The new project would see the US president’s company build 500 houses, plus swaths of commercial and leisure buildings, on the same estate that houses his Aberdeen golf course.

Trump Aberdeen was Trump’s first big investment in his mother’s homeland. Since he bought the piece of land in 2006 for $12.6 million in cash, according to the Washington Post (paywall), it has performed terribly: His company says it invested £100 million in building a golf course and club house there—the Post estimates a sum closer to $50 million (£38 million at current rates)—and the course has lost money every year since opening in 2012, racking up total losses of £7.1 million, according to its filings.

That didn’t stop Trump making an even more disastrous investment on the Scotland’s West coast: Trump Turnberry golf course, which he bought in 2014 for a reported £37.5 million in cash. Turnberry has lost nearly £30 million ($39 million) under Trump’s ownership. Trump claims he has spent £200 million fixing up the place; his project manager says it’s more like £140 million (paywall). Turnberry’s financial filings say Trump has loaned the course £112 million.

There seems to be little chance of turning around the courses’ fortunes; golf’s popularity in Scotland has been plummeting for a decade.

Undeterred, the Trumps now plan to expand the Aberdeen course with the massive development announced last month, grandly named the Trump Estate. The Trumps were given permission to build on the site amid much controversy over potential environmental damage, based on a promise that they would spend £1 billion on two golf courses, a luxury hotel and hundreds of homes. They’ve now scaled back the spending to £750 million, of which they say the current development is the second stage—its unclear which parts of the initial plan will be ditched. This second stage depends on them getting local council approval and then actually ponying up the money.

How Trump pays for it all

The new project is being paid for in cash, with no external loans, a Trump Organization spokesperson told Quartz. That fits an odd trend, recently uncovered by the Washington Post: In 2006, Trump quietly gave up his self-proclaimed mantle of “King of Debt,” and started making all his investments in cash.

The business model goes against industry trends. Developers tend to put a small amount of their own cash into projects, with banks funding the rest. This minimizes the developer’s risk and lets them invest more widely. Onlookers have struggled to explain both this new model and Trump’s Scottish projects. In a careful dissection of Trump Turnberry’s finances, the New Yorker’s Adam Davidson calls that investment “a bizarre, confounding move that raises questions about the central nature of his business.” Trump Aberdeen has a lot of the same traits.

Trump’s refusal to release his tax returns means we have precious little insight into his finances, but his illiquid property empire doesn’t seem suited to investing in huge projects with just cash. In 2016, the Wall Street Journal analyzed his campaign filings to estimate that, for an 18-month period starting Jan. 2014, the Trump Organization had a pretax income of $160 million. If the Journal’s guess is right, the $197 million investment in Aberdeen adds up to nearly two years’ revenue for the whole Trump Organization. (A Trump aide said at the time that the number is “wrong by a lot”—and campaign filings are far from reliable—but the company wouldn’t comment further).

So, where are they getting the money from? When the Post asked Eric Trump, who runs the golf side of the Trump business, how they had paid for 14 real estate projects worth $400 million since 2006, he insisted his father had “incredible cash flow and built incredible wealth…he didn’t need to think about borrowing for every transaction.”

If that’s the case, Trump Org either has some major revenue streams that analysts have missed, or the Trumps have been doing serious penny pinching. Spending so much carefully saved cash on two loss-leading golf courses in rural Scotland would be quite a decision, and a lot of ink has been spilled trying to explain it. Three main theories have arisen, of which two would be irrational business decisions, and the third, potentially unethical.

- Trump just loves golf.

- He was “‘mystically’ connected” (paywall) to projects in Scotland, his mother’s birthplace.

- He was actually investing someone else’s money (paywall); perhaps from Russia.

Maybe Trump just really loves golf?

Trump’s love of golf is not in doubt. He’s the best golfing president in US history, according to Golf Digest—though his friend and former world number two Suzann Pettersen says he “cheats like hell” on the course. In the year and a half he’s been in office, Trump has reportedly spent more than 100 days (paywall) at his golf courses.

He’s also immensely proud of the quality of his links. Trump Aberdeen’s financial disclosures boast that Florida-based Golf Week rates it the best modern course in Britain and Ireland. A plaque at the course itself says, without citing any sources, that it is “according to many, the greatest golf course anywhere in the world!”

Bloomberg’s Tim O’Brien, a Trump biographer and fierce critic, puts this simple love as the likeliest explanation for Trump’s Scottish golf spending. In Aberdeen, Trump has a world-class course that he built from scratch, and at Turnberry, he’s revamping a historic venue. Sure, they lose extraordinary amounts of cash, but what’s the point in being the world’s most famous mogul if you can’t waste a bit of money?

There’s something left out of this explanation though. Trump has courses around the world. As the New Yorker points out, in emerging markets, the burgeoning super-rich are crying out (pdf) for more golf. Why spend so much money in Scotland’s already saturated market, where golf is in decline?

Does Trump have a “mystical” attachment to Scotland?

Neil Hobday, a developer who worked with Trump on the Aberdeen development, told The Washington Post the mogul had a sentimental attachment to his mother’s place of birth. “He was, I believe, ‘mystically’ connected and hooked to this project. All my conversations with him were almost on an emotional rather than hard business level,” Hobday told the Post.

Trump’s mother grew up a long way from from the proposed new Trump Estate. Aberdeen is on Scotland’s east coast, while Mary Anne Trump is from the Isle of Lewis, a plane ride away on the west coast. Trump didn’t visit his mother’s actual birthplace until 2008 and only then on a stopover while he fought a legal battle over the rights to build the Aberdeen golf course. He strenuously denied the visit was a publicity stunt, despite spending just three hours on the island and a total of 97 seconds in his mother’s childhood home, according to the Guardian.

He also doesn’t seem too bothered by the country’s natural heritage. He spent years railing at the eco-friendly “ugly wind turbines” to be built off the coast of his Aberdeenshire estate. At the same time, the Trump Organization “partially destroyed” the estate’s sand dunes—a site of rare natural beauty and scientific interest—according to inspectors from Scottish Natural Heritage.

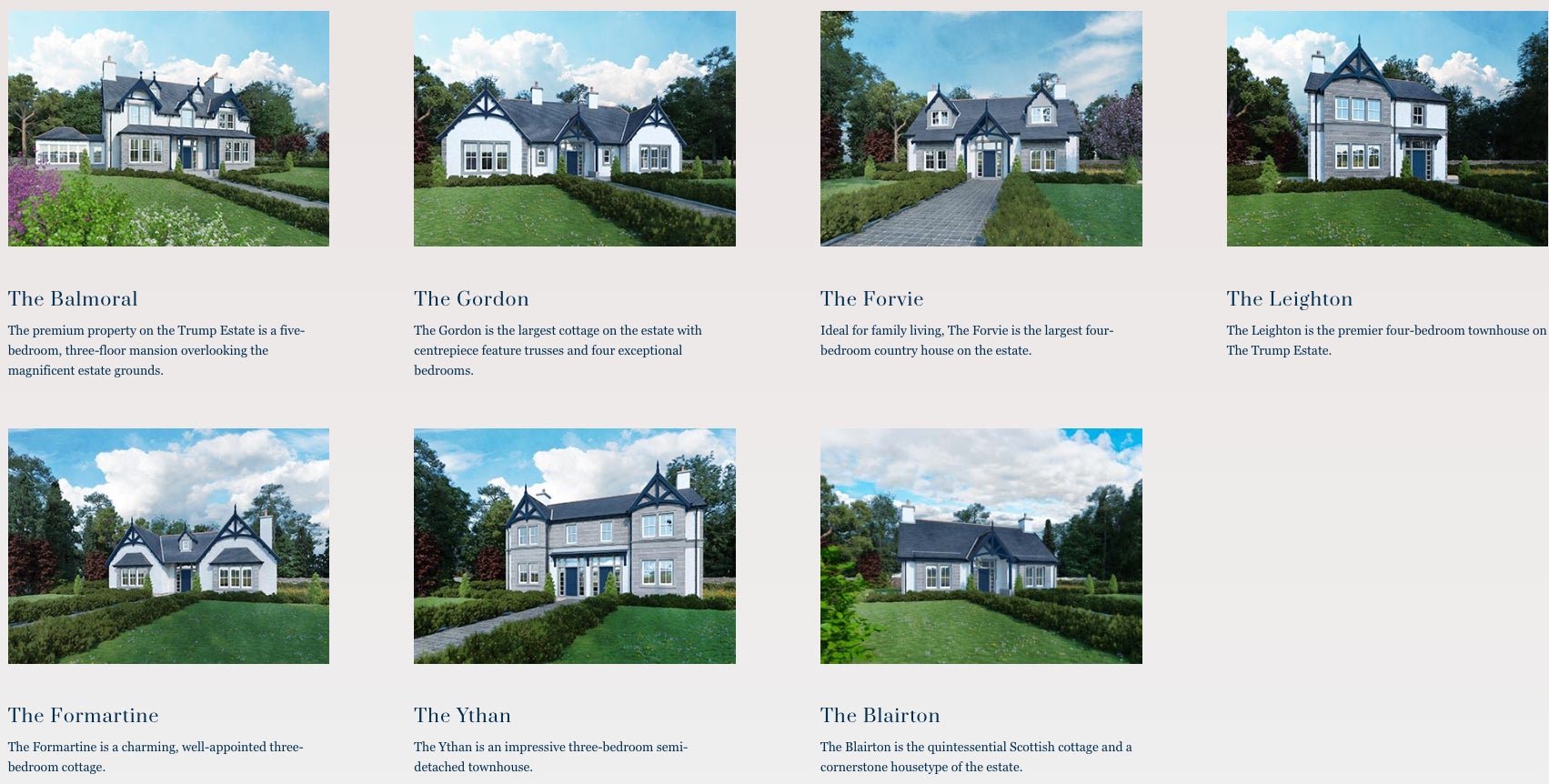

However, it’s possible that Trump’s connection to Scotland isn’t tied to his mother, but something more aspirational. The “Trump Estate” and his fabricated coat of arms (paywall) jive perfectly with Trump’s idea of European grandeur; designs for the new houses indulge clichés of Scottishness, presenting a Disney-fied version of what the Trump Estate brochure calls a “quintessential Scottish cottage.”

Is it someone else’s money?

It’s genuinely difficult to work out what in Trump’s business empire is producing so much cash that he can spend hundreds of millions without borrowing, leading some to speculate that the money is coming from a third party. What’s more, UK real estate is a notorious money-laundering hole; Scotland, in particular, has had serious problems with the issue.

The source of Trump’s cash has raised eyebrows before. In 1998 the US Treasury fined him $477,000 for breaking money-laundering rules at the Trump Taj Mahal casino property, and as Davidson points out in the New Yorker, there’s nothing in Trump’s history to suggest he’s troubled by working with deeply suspicious characters. Glenn Simpson, the Fusion GPS founder who commissioned former British spy Christopher Steele’s famous dossier, has said the question of Russian involvement in Trump’s golf course was “concerning” to his firm while it was conducting opposition research on Trump.

“If you’re familiar with Donald Trump’s finances and the litigation over whether he’s really a billionaire, you know, there’s good reason to believe he doesn’t have enough money to do this and that he would have had to have outside financial support for these things,” Simpson said in Congressional testimony (pdf), when asked if Russian money may be invested in Trump’s Scottish golf courses. “A lot of what I do is analyze whether things make sense and whether they can be explained. And that didn’t make sense to me, doesn’t make sense to me to this day.”

Eric Trump allegedly said himself that the Trumps received Russian funds. Golf journalist James Dodson claimed last year that during a 2013 round with Trump’s youngest adult son, he asked how the Trumps were funding their golf investments when no banks had “touched a golf course” since the 2008 recession. According to Dodson, Eric replied: “Well, we don’t rely on American banks. We have all the funding we need out of Russia…we’ve got some guys that really, really love golf, and they’re really invested in our programs. We just go there all the time.” Eric Trump has called Dodson’s anecdote “completely fabricated.”

What the money-laundering theory doesn’t answer, though, is why any partner would want to invest in Scottish golf sinkholes. Stashing cash in British property isn’t difficult, and there are plenty of lovely buildings that aren’t in the middle of nowhere and don’t cost millions per year to maintain. And yet, plenty of Russians keen to get their money out of the Kremlin’s reach have found happy homes in Trump’s US projects. The US president has built relationships with tycoons from several parts of the former Soviet Union—and golf has been in vogue with Russian oligarchs for quite a while. There’s also the grand theory that the Kremlin has long been working Trump, and invested in his properties either to gain leverage over him or as payment for work done.

Why this town in Aberdeenshire?

In part, the Trumps are acting on a longstanding promise: When the Trump Organization got planning permission to build the golf course on the heritage site, it promised to invest at least £1 billion in a massive local development. However, by 2014, after years of battles with authorities and local residents, Trump had soured on the idea. He ditched plans for a luxury hotel on the site, and announced he would focus all his “investment and energy” on a new course in Ireland—hardly the first time the Trump Organization had reneged on a promise.

So, why return to the plan now? For one thing, the Trumps love projects that grab headlines, their plan for dozens of affordable hotels across the US has gone nowhere, and, politically, Britain is a pretty anodyne place to be putting their cash, compared to previous projects in Azerbaijan, Turkey, and the Republic of Georgia. Plus, Scotland is having a commercial construction boom—albeit mainly driven by just two massive projects in Edinburgh and Glasgow—and housing market conditions “are probably at their strongest level in a decade,” says Oliver Knight, an associate at Knight Frank, an estate agent and property consultancy.

Aberdeen itself has been one of the UK’s “worst performing areas in the last couple of years,” Knight said, but the recent recovery in global oil prices has helped its local offshore drilling economy and real estate is starting to grow alongside that. Charles Dudgeon, the director of rural sales at the estate agent Savills, agreed that the timing is “probably pretty good” to invest in Aberdeenshire. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that the charming but unglamorous northeast of Scotland is “a rather odd place” for a glitzy New York tycoon to be sinking millions.

The estate’s prices per square foot are “at the level of some of the Aberdeen area’s top hotspots,” according to Faisal Choudhry, director of Scottish research at Savills. That’s despite its location being a 25-minute drive from Aberdeen itself. Choudhry guessed that the “slightly high” prices are due to the free golf-course membership given away with the properties. Those willing to forgo the golf membership and new appliances of the Trump Estate’s £1.3 million gaudy five-bedroom “mansion” named The Balmoral can find gorgeous period houses with as many or more bedrooms in Aberdeen’s toniest areas for around half a million less.

The project in some ways is a bet on oil markets and a post-Brexit Britain, both important factors in the future of the Scottish economy. But even if economic conditions are good, Trump Aberdeen is far from guaranteed success—the golf course was turning out consistent losses even before 2014, when oil prices were flying high and Britain had no plans to leave the EU. Given the uncertainty surrounding Britain’s economic future, the Trumps motives for investing now are all the more curious.