After spending his first weeks as US president-elect getting pounded with criticism about his potential conflict of interests, Donald Trump announced that Dec. 15 will bring a big reveal: Legal agreements freeing him from his companies—and ostensibly all the attendant ethics problems—are finally going to be made public.

The move would be necessary for any US president looking to avoid the taint of corruption. But no president has ever had to work as hard to untangle his business dealings as Trump will. And because there is so little information about the scope of his business and the full range of conflicts it potentially presents, it’s going to be hard to hold him accountable for doing it properly.

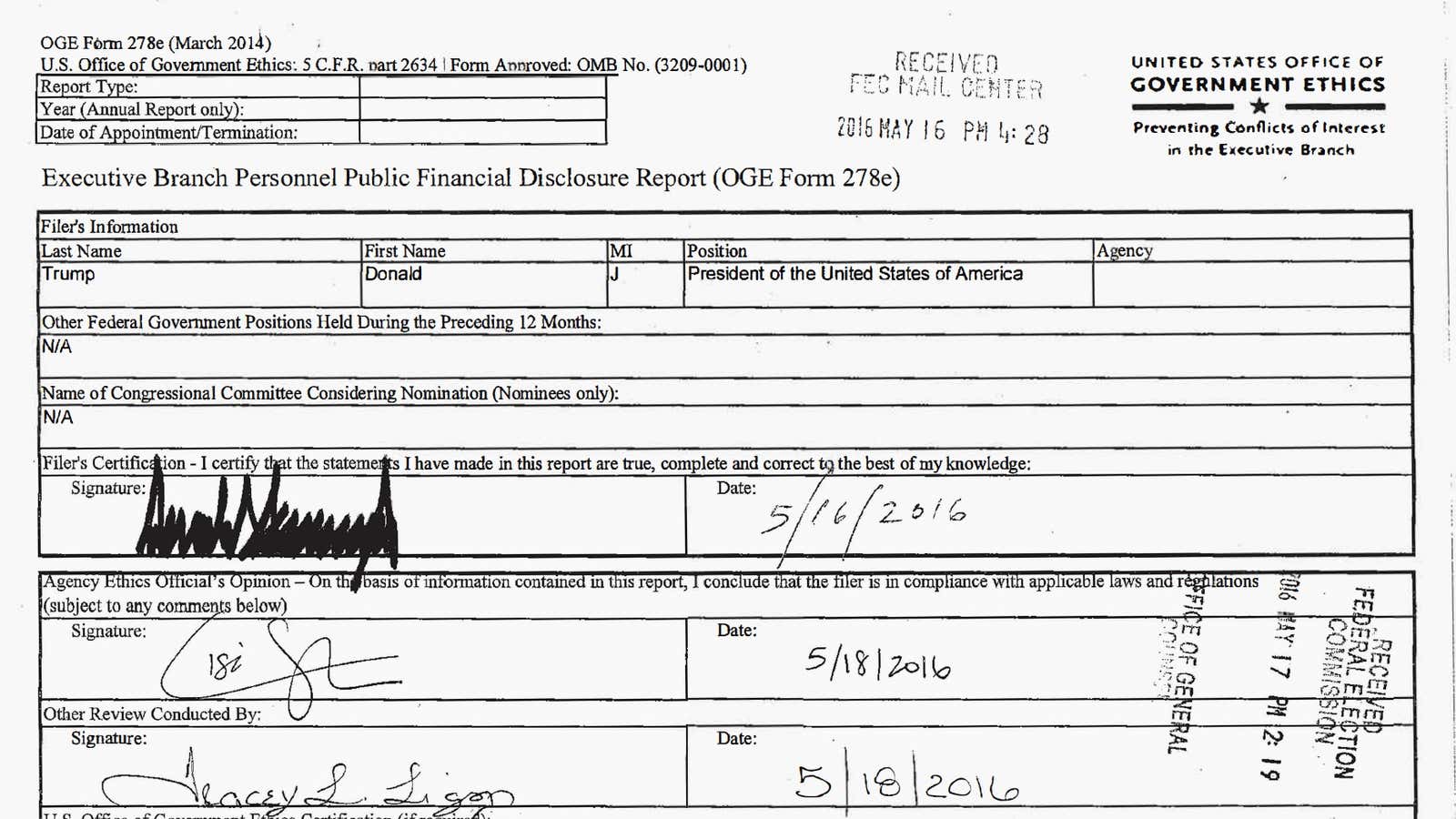

The only publicly available financial disclosure about his empire, a 92-page document that Trump once bragged was the “largest in the history” to be filed with the US Federal Election Commission, doesn’t tell us much about his financials, nor is it much of a disclosure. But it’s the best available source we have for trying to figure out his business entanglements.

So we trawled through it—and turned the pdf file into a digital spreadsheet, so that others can search it—with the aim of determining what Trump holds, where it is, and how much it’s worth.

The data is light on details

The disclosure lists more than 550 companies in Trump’s empire but provides scant detail on them. Unless they own an obvious asset (an airplane, for example) or hold the rights to one of his books, it’s often impossible to determine specifically what they do. And even when the purpose of the business is reasonably clear, the income from it frequently isn’t.

The disclosure form only requires that Trump report some major sources of income, such as rent and royalties, as a range. Rent from a residential property, for example, might generate anywhere from $100,001 and $1 million in income. Royalties from a licensing deal might bring in just over $1 million, or as much as $5 million.

The value of Trump’s companies is similarly opaque. Anything worth more than $50 million is simply listed as “Over $50,000,000.” Of Trump’s 152 disclosed assets, 24 fall into this top bracket—mainly his golf clubs, hotels, and large buildings. Each of those could be worth $50.1 million or $500 million.

In other cases, Trump reports that the value of many of his companies is “not readily ascertainable,” even when they generate significant income. And in still other cases, such as the Central Park carousel he rescued from obsolescence in 2010, he was prompted to provide a specific dollar amount.

Arguably more problematic than the shortage of precise dollar figures is that the disclosure doesn’t tell us anything about who Trump’s companies do business with.

The three entries above are listed in part two of the “Filer’s Employment Assets and Income” section of the disclosure. The rent is for a property in the French West Indies. We don’t know the identity of the renters. But that information might be quite useful for sorting out Trump’s relationships with foreign entities, when you consider that the state-owned Industrial & Commercial Bank of China is a renter at Trump Tower in New York.

As to the licensing royalties, from the document we can guess these are payments for using Trump’s name on a tower in Manila. When others have dug a little deeper, the situation has shown up as potentially troubling: His business partner there is now the Philippines’ envoy to the US. But the document shows us almost nothing about their contractual agreements, nor Trump’s level of control over that building, while guesses about the amount of money Trump earns on the deal could vary by a matter of millions.

Guessing about Trump’s global business interests

We know Trump has extensive business interests overseas, but few of his companies are registered abroad. In some cases we can surmise that his American companies are doing business outside the country because they have the name of a foreign place in the company name.

Take, for example, the companies listed as Trump Marks Batumi LLC, DT Marks Gurgaon LLC, and DT Marks Worli LLC. The names include places in Georgia (the country, not the US state), St Vincent and the Grenadines, and India—but only a well-honed knowledge of geography or intensive googling would allow you to pick all of them out.

Crucially, having these names doesn’t necessarily mean these companies are doing business in those places. Trump could create a company called DT Marks Berlin LLC and use it to do business anywhere from Bangkok to Boston to Bogota—or he could not use the company at all. Likewise, calling a company something vague like Trump Marketing LLC doesn’t mean it isn’t being used to do work abroad.

To illustrate the potential for confusion, we counted up the Trump businesses we think might operate abroad, and compared it with what the Washington Post found in its analysis, published in an excellent piece on Nov. 20. The Post counted 110 companies dealing with at least 18 countries or territories. By our count, there are 130 companies with interests in 23 countries:

Who’s right? Almost certainly neither of us. The disclosure simply doesn’t give us enough information to know for sure. Which means we don’t have enough information to know where Trump’s next foreign conflict-of-interest may spring from.

India, Argentina, Taiwan—and Delaware

In fact, of the scandals generated so far by Trump’s international dealings—his meeting with Indian business partners after the election, the suspicious progress of a Trump Tower project in Buenos Aires days after his phone conversation with Argentina’s president, his business interests in Taiwan—almost none could have been gleaned directly from the information in the disclosure. In most of these cases, it took on-the-ground journalism to help make those connections.

The limitations of Trump’s disclosure are magnified by the United States’ weak transparency laws for private companies. Delaware, where the vast majority of Trump’s companies are registered, is widely considered to be one of the world’s most opaque tax havens. Companies registered there can be set up in hours and be entirely anonymous. As the Wall Street Journal has documented, Trump’s use of Delaware LLCs further obscures his business interests.

What’s the filing actually good for then?

The most useful sections of Trump’s disclosure are probably those about his personal investments and his loans. That data has allowed reporters to, for example, make the connection between Trump’s position on the Dakota Access oil pipeline and a $15,000 to $50,000 stake he had in Energy Transfer Partners, the main company responsible for building it.

Trump now claims to have sold all of the stock he owned at the time of the disclosure, effectively nullifying any information from that part of the disclosure. But we don’t know if he subsequently purchased more stock, and he hasn’t shown evidence that he sold all his previous holdings. So, without another disclosure, future conflicts stemming from his private investments will be impossible to determine. In any case, as we’ve argued previously, his stock investments are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to his potential conflicts of interest. It’s through his own businesses that he could really enrich himself as president.

So, where does looking through the most detailed publicly available document about Trump’s assets leave us? Well, mostly with a lot of dry detail about how Trump’s businesses are organized. We know that he generally forms both an LLC and a corporation for his real estate dealings—a common strategy for limiting personal liability. We know he makes liberal use of shell companies to hold his assets. We know that about 30 of his businesses are co-owned with his family. We know that he rarely co-owns properties with outside partners. None of these things are particularly surprising.

As Trump has pointed out, the weakness of conflict-of-interest regulations on the president mean that on a purely legal basis, if not an ethical one, he isn’t obligated to declare more. But this leaves the American public with nowhere near what it is owed to be sure the next president isn’t using his position for personal profit or for the benefit of the people or firms he’s indebted to.

Will the Dec. 15 announcement provide anything more satisfying? There is little Trump has done so far to give the impression that this will be the case. If he can’t let go of his role as executive producer on Celebrity Apprentice, then it will be quite a surprise if he provides clear plans for recusing himself from more weighty matters, like his connections with Deutsche Bank and the entanglements with the US Department of Justice.

Browse the spreadsheet and send us your tips

We’re making our searchable spreadsheet (cross-referenced, where possible, with data from Open Corporates) as well as the original PDF (made searchable as well) available for private citizens and the media to scrape through. We welcome tips from anyone with more information on any Trump-linked company that may or may not be registered.

Max de Haldevang <[email protected]> (PGP fingerprint: B284 521F 0DD8 17C7 AA6E 9938 BED0 D4BF 4820 93)

Chris Groskopf <[email protected]> (PGP fingerprint: 9D2F F7F8 83C0 E286 25B5 3BA2 B7C0 7A1B 908A E1)