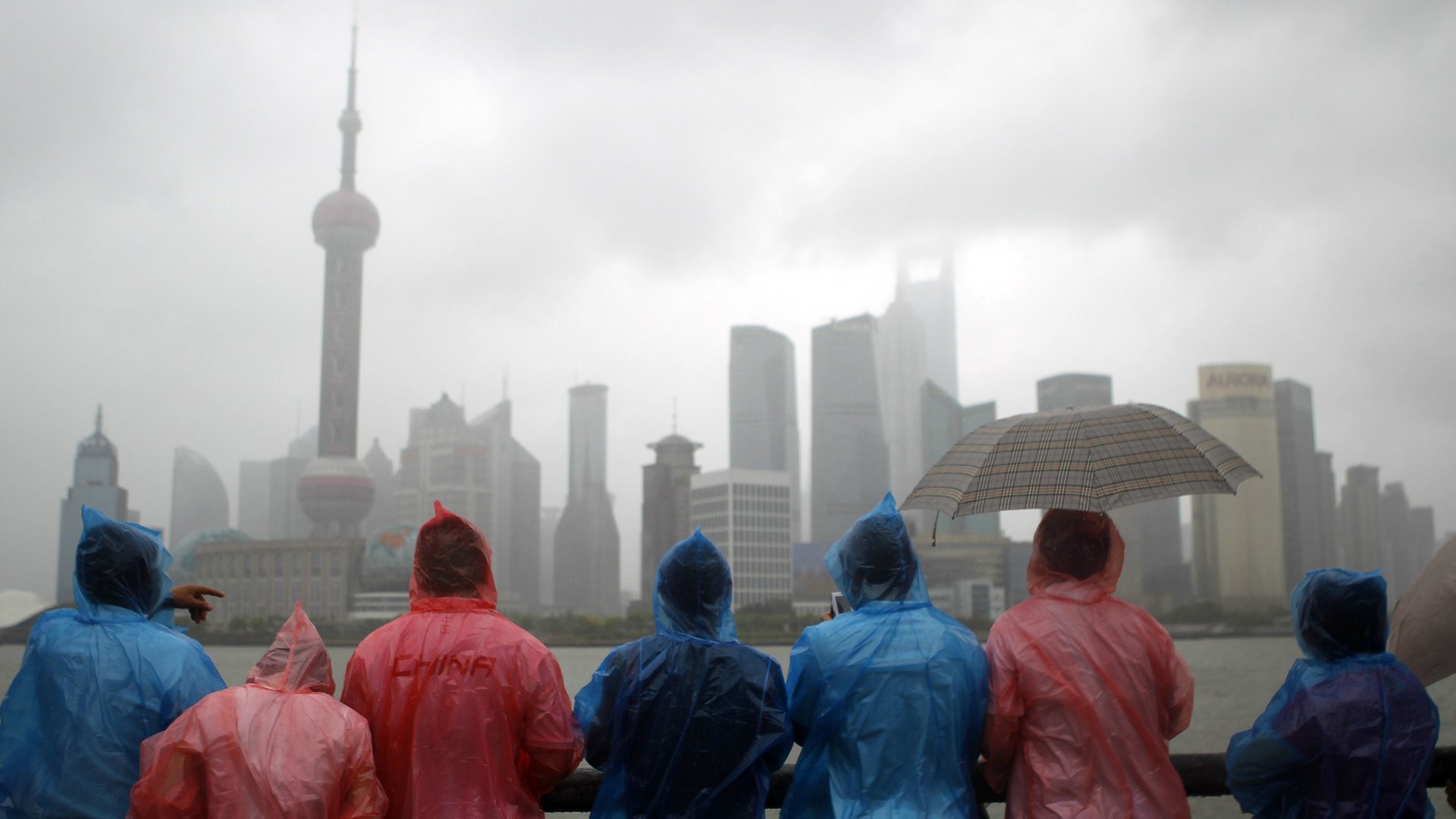

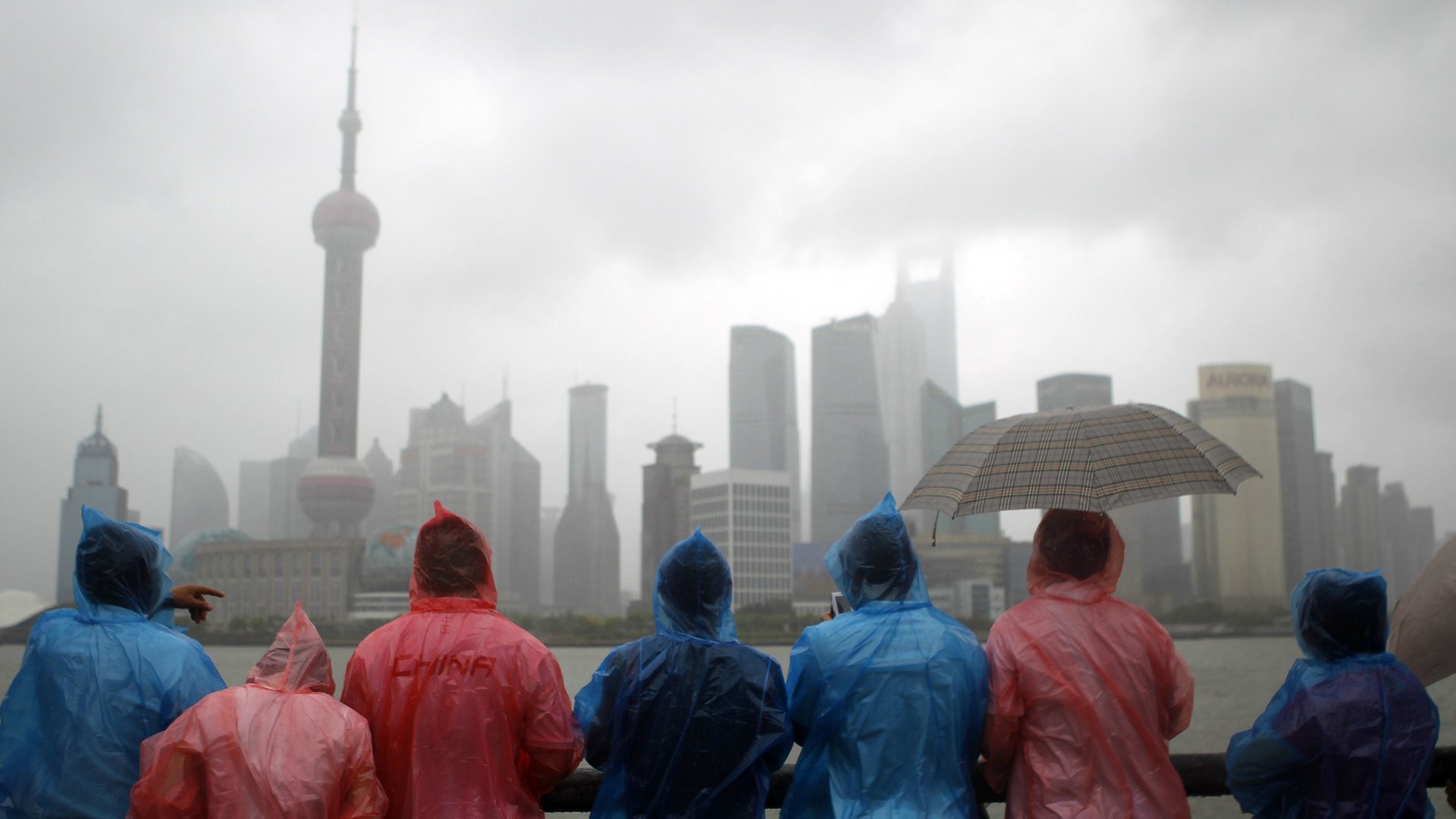

For all its economic dynamism, China’s income mobility is bad and getting worse

The decline of poverty in China is perhaps the greatest economic story of the past half-century. From 1981 to 2013, the share of Chinese people in extreme poverty, according to the World Bank’s definition, fell from 88% to 2%. This is an astonishing improvement.

The decline of poverty in China is perhaps the greatest economic story of the past half-century. From 1981 to 2013, the share of Chinese people in extreme poverty, according to the World Bank’s definition, fell from 88% to 2%. This is an astonishing improvement.

But it could always be better. In an ideal world, the children of parents born into the poorest Chinese households would have as good a chance of making it to the top as those born rich. But like in most countries, that is not the case. Nearly everybody in China is doing better than their parents, but children from higher-income households are gaining the most.

A new study by economists at the National University of Singapore and The Chinese University of Hong Kong finds that children born to parents in the top 20% of income were nearly seven times more likely to remain in the top 20% as adults than those born into the bottom 20% were to rise to the top. The data come from the China Family Panel Studies and include children born between 1981 and 1988 who have worked for at least three years.

China’s economic mobility statistics are even more extreme than what is found in most rich countries. For example, a recent study (pdf) examining the economic mobility of children born in the US in the mid-1980s found that those from the poorest 20% of households had about a 9% chance of reaching the top 20%, compared with around 7% in China. US children from the top 20% were also far less likely to stay at the top in adulthood relative to their Chinese counterparts.

Not only is China’s economic mobility low, but it seems it seems to be getting worse. According to the study, children born into low-income households in the 1970s had a better chance of rising up the ladder than those in the 1980s.

The researchers think the decrease in mobility in China may be a result of the expansion of higher education. Only parents with means can afford to send their kids to the best schools, and in a job market that increasingly rewards high-skill workers, this perpetuates income status.

The researchers believe one way to increase income mobility across generations would be to remove restrictions on rural-to-urban migration within China, as higher rates of migration particularly help the poor. Currently, rural residents are not able to permanently move to cities like Beijing without passing specific qualifications.