Everything bad about Facebook is bad for the same reason

In June 2016, Antonio Perkins unintentionally broadcast his own death to the world. It was a sunny day in Chicago, and he was sharing it on Facebook Live, a platform for distributing video in real-time, released just a few months earlier.

In June 2016, Antonio Perkins unintentionally broadcast his own death to the world. It was a sunny day in Chicago, and he was sharing it on Facebook Live, a platform for distributing video in real-time, released just a few months earlier.

The video is long. It features Perkins doing mundane summer things. Standing around on the sidewalk. Complaining about the heat. About six minutes in, suddenly, gun shots ring out. The camera moves frantically, then falls to the ground. Later that day, Perkins was pronounced dead.

The video has close to a million views.

The Ugly

The next day, a memo called “The Ugly” was circulated internally at Facebook. Its author, Andrew Bosworth, one of the company’s vice presidents and central decision makers.

“We talk about the good and the bad of our work often,” the memo, obtained by BuzzFeed in March, begins. “I want to talk about the ugly.” It continues:

We [at Facebook] connect people…Maybe it costs a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. And still we connect people. The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is de facto good. [emphasis added]

The memo does not mention Perkins. It’s possible Bosworth was not aware of the incident. After all, real-time tragedies are not that rare on Facebook Live.

But Perkins’ live-streamed death is a prime example of “The Ugly.” Although his death is tragic, the video does not violate the company’s abstruse community standards, as it does not “glorify violence” or “celebrate the suffering or humiliation of others.” And leaving it up means more people will connect to Perkins, and to Facebook, so the video stays. It does have a million views, after all.

The decision is one of many recent Facebook actions that may have left a bad taste in your mouth. The company unknowingly allowed Donald Trump’s presidential campaign to collect personal data on millions of Americans. It failed to notice Russia’s attempts to influence the 2016 election; facilitated ethnic and religious violence in several countries; and allowed advertisers to target such noble categories of consumers as “Jew haters.” Not to mention that fake news, conspiracy theories, and blatant lies abound on the platform.

Facebook didn’t intend for any of this to happen. It just wanted to connect people. But there is a thread running from Perkins’ death to religious violence in Myanmar and the company’s half-assed attempts at combating fake news. Facebook really is evil. Not on purpose. In the banal kind of way.

Underlying all of Facebook’s screw-ups is a bumbling obliviousness to real humans. The company’s singular focus on “connecting people” has allowed it to conquer the world, making possible the creation of a vast network of human relationships, a source of insights and eyeballs that makes advertisers and investors drool.

But the imperative to “connect people” lacks the one ingredient essential for being a good citizen: Treating individual human beings as sacrosanct. To Facebook, the world is not made up of individuals, but of connections between them. The billions of Facebook accounts belong not to “people” but to “users,” collections of data points connected to other collections of data points on a vast Social Network, to be targeted and monetized by computer programs.

There are certain things you do not in good conscience do to humans. To data, you can do whatever you like.

Life as a database

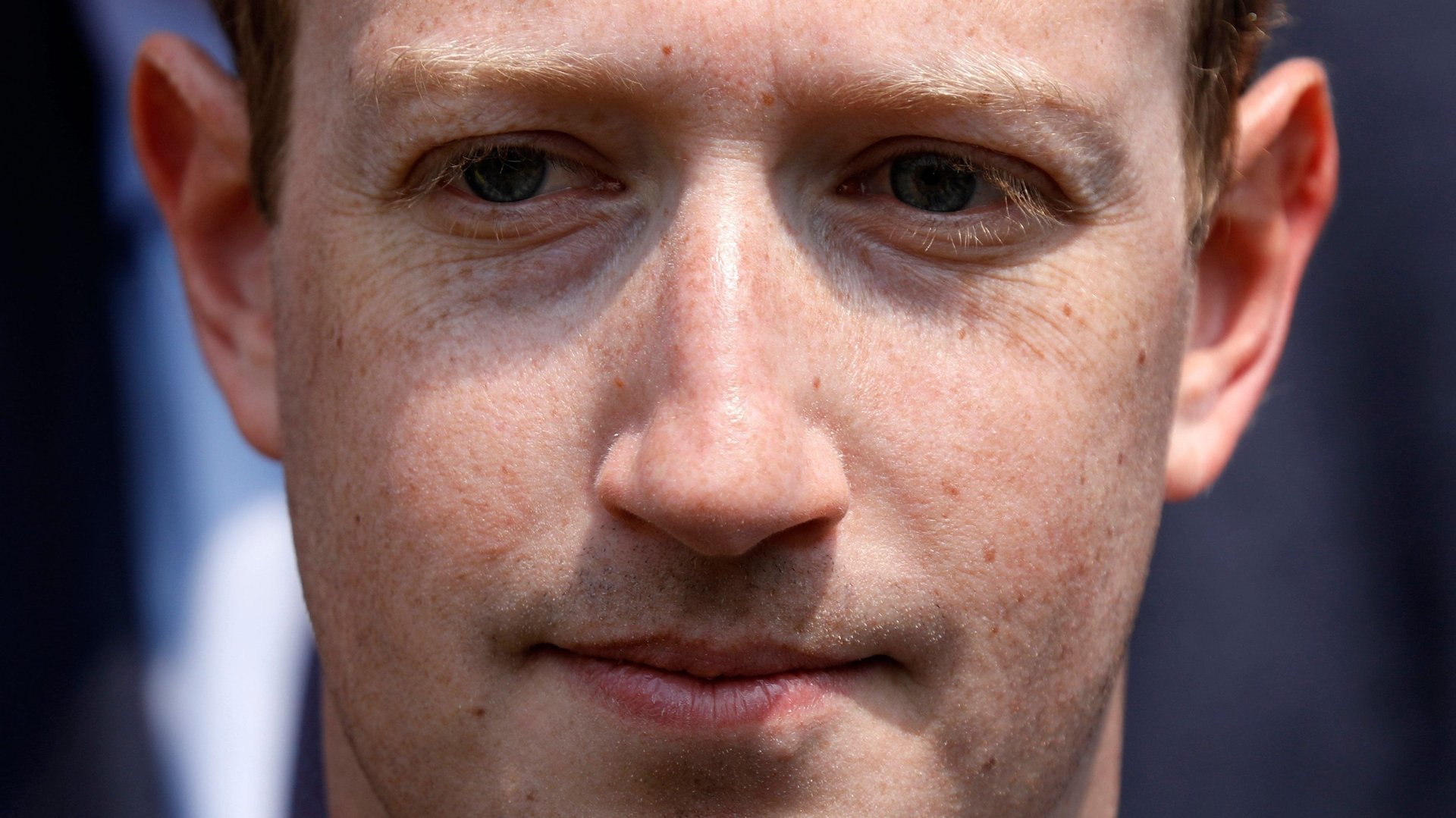

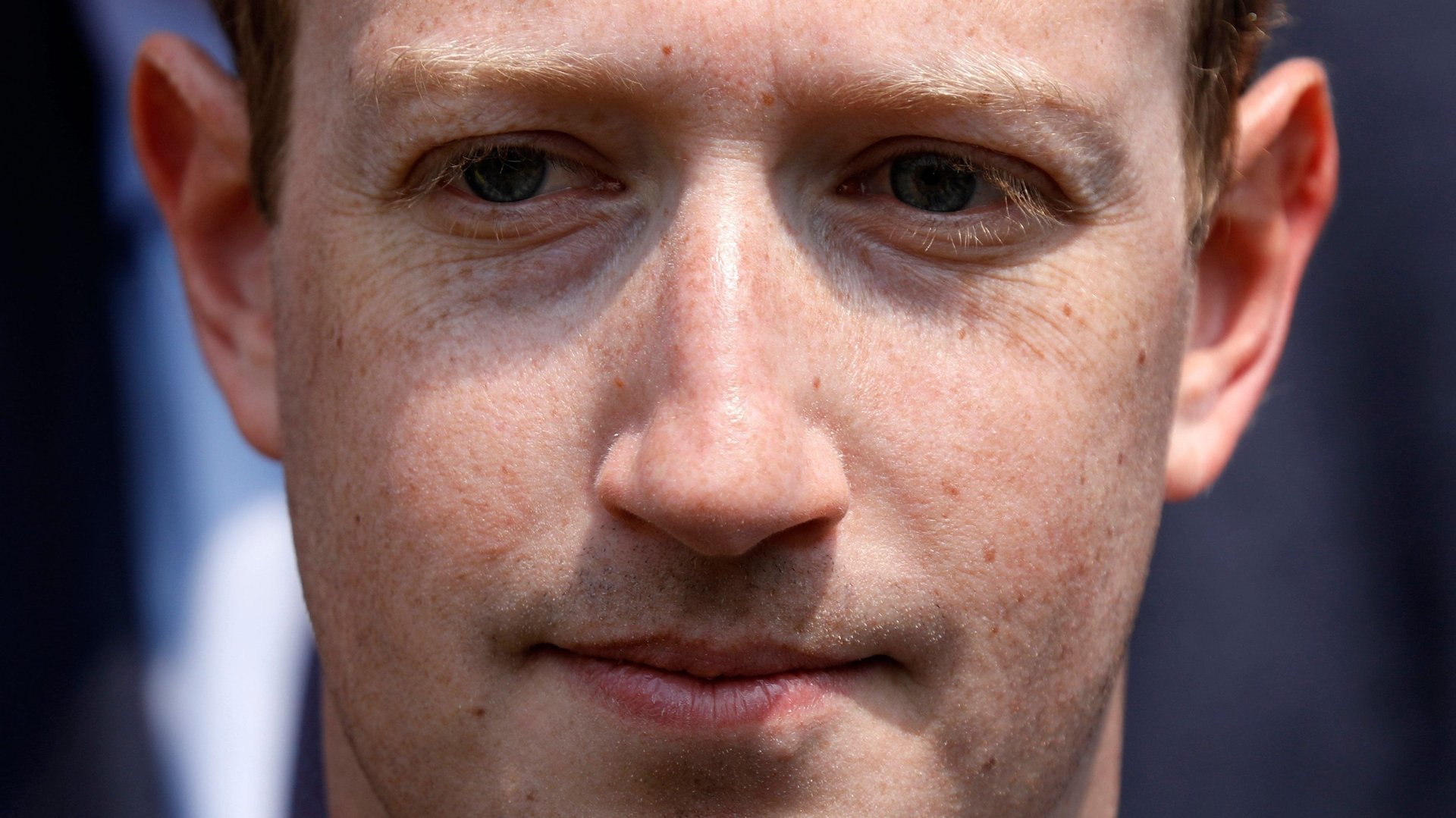

Since the public release of “The Ugly,” Bosworth has distanced himself from the argument the memo makes. He now says he merely wanted to “surface issues” and that he, rather unbelievably, “didn’t agree with it even when [he] wrote it.” Mark Zuckerberg added that he, too, strongly disagreed with the memo, saying, “We’ve never believed the ends justify the means.”

Time and again, though, Facebook’s choices have revealed that connecting people is considered a de facto good in nearly all cases. It’s why Zuckerberg, in a recent interview with Recode, defended the decision to allow posts from deniers of both the Sandy Hook shooting and the Holocaust, saying they just “get things wrong.”

With Facebook, “life is turned into a database,” writes technologist Jaron Lanier in his 2010 book You Are Not a Gadget. Silicon Valley culture has come to accept as certain, Lanier writes, that “all of reality, including humans, is one big information system.” This certainty, he says, gives the tech world’s most powerful people “a new kind of manifest destiny.” It gives them “a mission to accomplish.”

Accepting that mission is convenient for Facebook. It makes scaling as fast as possible a moral imperative. In this view, the bigger Facebook is, the better the company is for the world. This also happens to be the way for it to make the most money.

The problem, says Lanier, is that there is nothing special about humans in this information system. Every data point is treated equally, irrespective of how humans experience it. “Jew haters” is just as much an ad category as “Moms who jog.” It’s all data. If Group A has a bigger presence on Facebook than Group B, so be it, even if Group A is trying to demean or organize violence against the Bs. Of course, the reality is that humans are all different, and cannot be reduced to data.

Try telling that to the group of Ivy League white boys who started Facebook as a hot-or-not website and invented a facial-recognition keg.

What it means to think

Facebook’s mistake is not new. In general, things get ugly when massive, powerful organizations fail to consider the humanity of others. We are going to talk about Nazis now.

The best analysis of Facebook’s intellectual failure comes from political theorist Hannah Arendt in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem. The book is an account of the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann. A mid-level Nazi bureaucrat, Eichmann was chiefly responsible for the logistics of forcibly transporting Jews to concentration camps during the second World War.

Eichmann was captured in Argentina and brought in front of an Israeli court to explain his crimes. Everyone present expected him to be a sadistic madman, perversely obsessed with the destruction of the Jewish people.

Instead, he revealed himself to be a buffoon and a careerist. He claimed to have forgotten the details of major political events while remembering clearly which of his peers got a promotion he coveted. According to Arendt, one Israeli court psychiatrist who examined Eichmann declared him “a completely normal man, more normal, at any rate, than I am after examining him.”

The question that haunted Arendt was how such a “normal” man had played a major role in mass murder. Eichmann knowingly sent thousands of Jews to certain death.

Arendt concludes that it was neither sadism nor hatred that drove Eichmann to commit these historic crimes. It was a failure to think about other people as people at all.

A “decisive” flaw in his character, writes Arendt, was his “inability ever to look at anything from the other fellow’s point of view.”

How was it that Eichmann, and hundreds of other Nazis, failed to possess a basic understanding of the sanctity of human life? The answer lies in Eichmann’s belief in a grand, historical project to establish a racially pure “utopia.” This project transcended human lives, rendering them secondary. One life, or a million lives, were small prices to pay for the promise of bringing about a “thousand-year Reich.”

Eichmann’s inability to think about the suffering of others arose from his internalization of the supreme importance of a grand project, Arendt concludes. Because the project must be completed no matter the cost, anything that furthers it is de facto good. That logic can distort the social norms that we take for granted, even inverting something as fundamental as “murder is wrong” into “murder of those who stand in the way of the project is right.”

Such demented logic does not hold up to even the slightest bit of scrutiny. But Eichmann, like those around him, shielded himself from the reality of his actions using emotionless abstractions. “Clichés, stock phrases, adherence to conventional, standardized codes of expression and conduct have the socially recognized function of protecting us against reality,” Arendt wrote in an essay called “Thinking,” published in The New Yorker 15 years after the Eichmann book. The events and facts of the world should be always pressing on our “thinking attention,” she writes, forcing us to reevaluate our behaviors and beliefs.

“Eichmann differed from the rest of us,” she concludes, only in that there was no connection between reality and his thought process. Instead, he blindly followed the twisted morality that had become conventional in his circles. And millions died because of it.

That brings us back to Facebook. It has its own grand project—to turn the human world into one big information system. This is, it goes without saying, nowhere near as terrible as the project of the thousand-year Reich. But the fundamental problem is the same: an inability to look at things from the other fellow’s point of view, a disconnect between the human reality and the grand project.

The downward-sloping arc of the historical project

Arendt helps us to see how all of Facebook’s various missteps are related. Here’s an example that, while minor, illustrates the point.

Last year, Mark Zuckerberg released a video showing off Spaces, Facebook’s new virtual reality platform. In it, he is represented by a shiny, big-headed, smiley, computer-generated version of himself.

This Zuck caricature is seen first outside, on the roof of Facebook’s headquarters. He then pulls out some kind of orb. The orb, he says, contains a 360-video of Puerto Rico taken shortly after the devastation of Hurricane Maria. This orb is placed in front of the camera. Suddenly, Zuck–along with the avatar of Rachel Franklin, head of social virtual reality at Facebook–”teleports” into the scene. These two figures are now seen “riding a truck” through ruined neighborhoods and “standing” in feet of floodwater.

Oh, they forgot to mention just how cool this technology is, so they stop to high-five.

“It feels like we’re really here in Puerto Rico,” digi-Zuck says (remember this is all in subpar CG). They jump around to various disaster scenes for a couple minutes. “All right, so you wanna go teleport somewhere else?” Another orb and they are whisked away, back to California.

To those of us outside the grand project of Facebook, this video was obviously a terrible idea. News outlets ridiculed it as tone-deaf and tasteless. Even so, the video made its way through Facebook’s many layers of approval. The fact that people at Facebook gave it the thumbs-up when the video’s problems were so clear to outside viewers is indicative of the extent to which Facebook’s value system has diverged from that of the rest of society—the result of its myopic focus on connecting everyone however possible, consequences be damned.

With that in mind, the thread running through Facebook’s numerous public-relations disasters starts to become clear. Its continued dismissal of activists from Sri Lanka and Myanmar imploring it to do something about incitements of violence. Its refusing to remove material that calls the Sandy Hook massacre a “hoax” and threatens the parents of murdered children. Its misleading language on privacy and data-collection practices.

Facebook seems to be blind to the possibility that it could be used for ill. In Zuckerberg’s recent interview with Recode’s Kara Swisher, she mentions meeting with product managers for Facebook Live. They seemed “genuinely surprised,” she said, when she suggested that it might be used to broadcast murder, bullying, and suicide. “They seemed less oriented to that than towards the positivity of what could happen on the platform,” she says.

Those worst-case scenarios did happen, as the video of Antonio Perkins graphically demonstrates. Not because Facebook wanted anyone to get hurt. All because, at some point, it protected itself from human reality with computer programming jargon, clichés about free speech, and stock phrases asserting the “positivity” of a techno-utopia that, if realized, would have the nice side effect of generating boatloads of cash.

Facebook has fallen prey to Arendt’s fundamental error.

Think for yourself

Zuckerberg in fact hints at this reading of his company’s failures in a 6,000-word manifesto he wrote last February on Facebook’s future ambitions. About 4,500 words in, he admits that Facebook has made mistakes, saying he “often agrees” with critics. (He doesn’t say about what specifically.) But, he adds, “These mistakes are almost never because we hold ideological positions at odds with the community, but instead are operational scaling issues.”

It is true that Facebook rarely holds “ideological positions at odds with the community.” Since Facebook is banal, it typically lacks ideological positions about anything at all. The social-media platform has long tried to position itself as a bastion of neutrality, a platform for other people’s ideas, a passive conduit. When Swisher challenged Zuckerberg on allowing Sandy Hook deniers to spread their message, he said, “Look, as abhorrent as some of this content can be, I do think that it gets down to this principle of giving people a voice.”

But an organization with so much influence does not need to be ideologically opposed to society to cause harm. It only needs to stop thinking about humans, to feel comfortable dismissing religious violence, ethnic discrimination, hate speech, loneliness, age discrimination, and live-streamed death as “operational scaling issues.” To think of suicide as a “use case” for Facebook Live.

These days, it may be tempting to argue that Facebook is on the right path. The company’s mission statement was changed last year to reduce the importance of “connections.” Instead of “make the world open and connected,” its goal is now to “bring the world closer together.” In July, Facebook announced that it will start taking down posts that call for physical violence in some countries.

That is not nearly enough. The new mission still fails to do what Arendt says it must. It still puts Facebook, the platform, above the humans who use it. Bringing the world closer together can mean facilitating bake sales and Bible readings; it can also mean uniting the KKK and skinheads. The mission statement has nothing to say about the differences between the two.

Facebook needs to learn to think for itself. Its own security officer, Alex Stamos, said as much in his departing memo, also acquired by BuzzFeed. “We need to be willing to pick sides when there are clear moral or humanitarian issues,” he writes. That is what Eichmann never did.

The solution is not for Facebook to become the morality police of the internet, deciding whether each and every individual post, video, and photo should be allowed. Yet it cannot fall back on its line of being a neutral platform, equally suited to both love and hate. Arendt said that reality is always demanding the attention of our thoughts. We are always becoming aware of new facts about the world; these need to be considered and incorporated into our worldview. But she acknowledged that constantly giving into this demand would be exhausting. The difference with Eichmann was that he never gave in, because his thinking was entirely separated from reality.

The solution, then, is for Facebook to change its mindset. Until now, even Facebook’s positive steps—like taking down posts inciting violence, or temporarily banning the conspiracy theorist Alex Jones—have come not as the result of soul-searching, but of intense public pressure and PR fallout. Facebook only does the right thing when it’s forced to. Instead, it needs to be willing to sacrifice the goal of total connectedness and growth when this goal has a human cost; to create a decision-making process that requires Facebook leaders to check their instinctive technological optimism against the realities of human life.

Absent human considerations, Facebook will continue to bring thoughtless, banal harm to the world. The 2.5 billion people who use it, as part of their real lives, won’t put up with that forever.