DJI is turning robot battles into the next college sport—advantage China

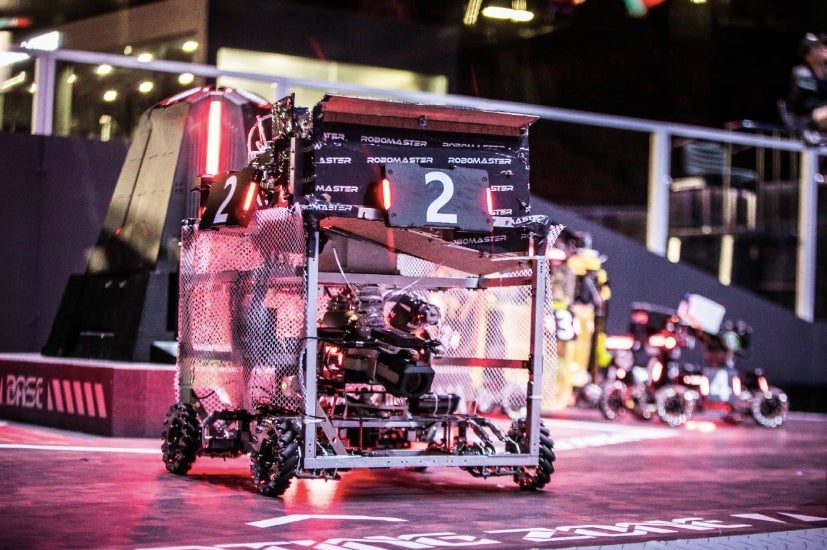

Last week, armies of robots landed in the city of Shenzhen—China’s paradise for hardware manufacturing—and shot pellets at one another in a cocoon-like stadium. As many as 10,000 people were in the stands cheering for the teams controlling them. The contest marries laboratory engineering with battlefield tactics—and it might become a phenomenon among engineering students worldwide.

Last week, armies of robots landed in the city of Shenzhen—China’s paradise for hardware manufacturing—and shot pellets at one another in a cocoon-like stadium. As many as 10,000 people were in the stands cheering for the teams controlling them. The contest marries laboratory engineering with battlefield tactics—and it might become a phenomenon among engineering students worldwide.

The RoboMaster competition was conceived by Shenzhen-based DJI, the world’s largest drone maker, and first launched publicly in 2015. It has since spread rapidly across China’s college campuses—as many as 150 Chinese universities entered the tournament this year. DJI has made an aggressive push to boost the competition’s popularity, including broadcasting matches on Chinese live-streaming sites, where they attract millions of viewers. The company even paid for an animated series centered on RoboMaster that was broadcast on Tencent Video, one of the country’s major video portals.

Now DJI is attempting to make RoboMaster more global by courting overseas universities. The finals of the most recent tournament, which ended Sunday (July 29), streamed with English and Chinese commentary on Twitch, an Amazon subsidiary. This year, teams representing 14 universities outside mainland China came to the competition. Schools from the US, Singapore, and Hong Kong placed into the top 32 teams. Japan’s Fukuoka University broke into the top 16. Shuo Yang, DJI’s RoboMaster project manager, says the company hopes to eventually create regional RoboMaster tournaments in North America and Japan, and also launch summer camps and education programs under the brand.

For DJI, RoboMaster is an opportunity to get more young people interested in robotics and aware of the DJI brand—and to spot engineering talent it can recruit. More broadly, it’s another example of China’s tech prowess slowly moving into the international spotlight.

Heroes, infantry, and drones

Robot competitions are already very popular in China, where a number of shows pit battle-ready machines against one another in a “fight to the death” (not unlike the TV program BattleBots, which drew in viewers in North America nearly two decades ago and was recently revived in the US).

RoboMaster, however, plays out more like soccer or laser tag than a robot-powered boxing match. Teams control six types of robots (eight in total), each with a specific set of functions. Some bots move around a terrain and shoot pellets in hopes of draining the opposition’s “hit points” (think of this as the bar that signifies a player’s “life” in a video game). Others collect ammunition or revive dead robots. Tension during a match will ebb and flow—there are slow moments where teams recalibrate and plan their next move, followed by bursts of shooting. A combination of luck and tactics can lead to upset victories.

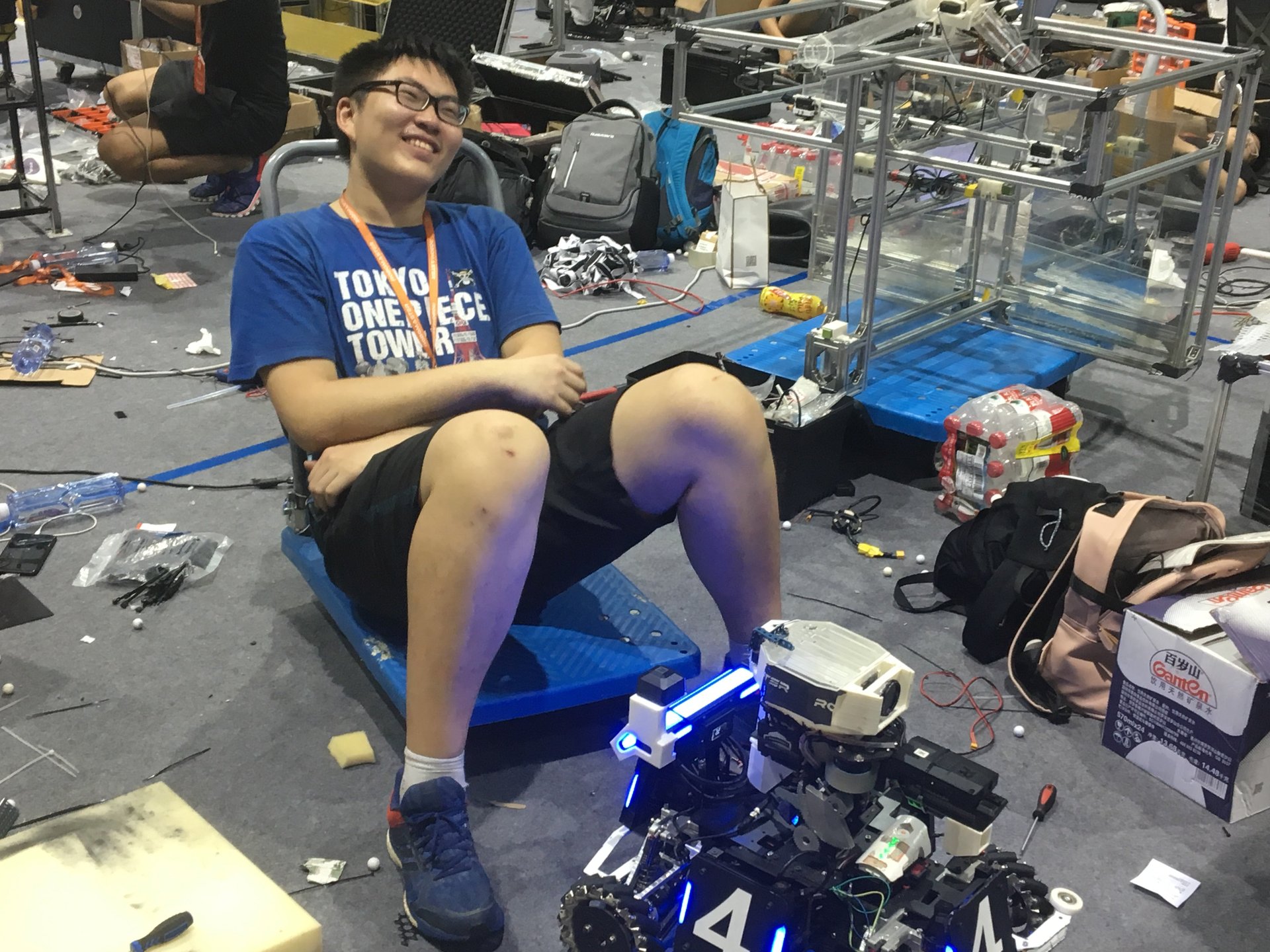

“It’s sometimes technical, sometimes strategy,” says Mengyu Liu, who writes code and controls the drone for a team from Southeast University, located in the eastern Chinese city of Nanjing. “To win the competition you must combine both.” Liu’s team was eliminated during the tournament’s wild card round and failed to enter the top 32.

The winner of yesterday’s final, taking home a trophy and $75,000, was a team from South China University of Technology, located in Guangzhou, a city about two hours northwest of Shenzhen. To date, Chinese teams have largely outperformed their overseas rivals. That’s to be expected given their head start. The competition originated in China and is already well known in university engineering departments across the country. Some schools even offer course credit to join a team, in lieu of taking other classes.

Making RoboMaster more international, however, will require increasing the number of overseas teams that participate. And as this year’s contest shows, those teams will have to work harder than their Chinese counterparts in order to compete on a more level playing field.

Manufacturing victory

Building a set of robots can easily take a full academic year, team engineers tell Quartz. While students can build their machines with DJI-sourced or off-the-shelf components, many choose to custom-make specific parts. That’s one area where a clear rift divides the Chinese teams from the non-Chinese ones—one emblematic of China’s strength in tech manufacturing.

In China, an abundance of small factories makes it easy for almost anyone to get a mechanical component custom-made cheaply and quickly. For example, when students on the Southeast University team were building their sentry robot (which glides along a raised rail to shoot at opponents), they needed to build a part that connected the machine’s upper and lower halves. After opening up Baidu Maps (China’s equivalent of Google Maps), they quickly found a suitable factory located 10 minutes from their campus by car. The part was ready in days and cost 400 yuan (about $60). “We didn’t even have to wait for shipping,” says Liu.

In the US, students at Virginia Tech had to be more resourceful. In March, team captain Yipin Zhou found himself looking for a factory that could custom build parts to connect a robot’s wheels to one of its motors. Zhou emailed a factory located 20 minutes from campus, asking for a quote. He received a reply one week later stating that his order could be completed in three weeks, with each part costing $100.

“I said screw it,” Zhou recalls. Instead, the Zhengzhou native used his personal connections to locate a factory in Shenzhen that gave him a much better quote—just 100 yuan (about $14.50) per part. “They manufactured it and sent it to the US in one week, and it was six times cheaper,” he adds.

As the competition approached, Zhou and his teammates wanted to move even faster. Conveniently, one team member’s family owned a vacant apartment in Foshan, a manufacturing hub roughly 100 km (62 miles) from Shenzhen. Once the school year ended, the students packed their bags and holed up in the three-bedroom unit. For a workspace, the same team member’s high school teacher let them build their robots in an unused lab. Not content to go back and forth with factories testing their designs, they bought their own machinery and manufactured part designs themselves. “You can get anything you want in almost one hour. That’s why we chose Foshan,” says Zhou.

Dependence on China

Tech companies and hardware entrepreneurs all over the world share some version of Virginia Tech’s predicament. China’s manufacturing ecosystem is so vast and efficient that it seldom makes economic sense to manufacture a part or product anywhere else. Building a robot—or e-cigarette, or electric scooter, or wifi-connected toaster—that will outperform competitors requires constant fine-tuning and iteration. The closer one is to a manufacturing hub like Shenzhen or Foshan, the faster one can make these small but critical tweaks.

Overseas policymakers and businesses must face a reckoning. China currently has certain advantages in manufacturing and engineering over other countries. These advantages might extend to fields like artificial intelligence and semiconductors as the government carries out its “Made in 2025” directive, a broad policy to boost the country’s tech sector, particularly advanced manufacturing. Foreign entities, now and in the future, will have little choice but to tap into China’s network of technology and knowledge in order to stay competitive.

For overseas RoboMaster teams, dependence on China has no political stakes. It might mean merely spending extra time on Taobao, an online shopping site, searching for parts, or finding creative ways to get closer physically to Shenzhen (many of the teams have native Chinese players, making it easier). For overseas companies and lawmakers, it’s more complicated. Washington, for example, has largely barred Chinese network equipment companies from selling to carriers, citing concerns about surveillance or national security. But the era of 5G is approaching, and the most advanced providers are from China (paywall).

The next big college sport?

There are other hurdles in DJI’s attempt to make RoboMaster a genuinely international undertaking. Language barriers, for instance, are steep: This year’s rule book came out in English one month after it was released in Chinese.

Increasing interest in the tournament from overseas engineering students might help solve some of these problems. Eric de Winter, captain of the University of Washington team, hopes to work with other North American colleges to start an online English-language forum to crowdsource translations and share ideas. That would be similar to the large Chinese-language forum where domestic teams communicate with one another.

Closing the gap in manufacturing will be more difficult than breaking down a language barrier. But de Winter says this is a challenge overseas teams should embrace.

“It’s just kind of the real world,” he says. “If there’s a wonderful electronics market in your backyard, you should take advantage of that—I know I would.” His team resorted to using the machinery at the university to build custom parts.

De Winter adds that there’s ample opportunity for RoboMaster to grow more popular overseas. He compares it to the world of e-sports, but with more the human drama and random surprises found in athletic sports. Much as a star basketball center might suddenly get injured, a “star robot” might abruptly break down. That could throw off a team’s winning streak—or make a victory all the more stunning.

“They have quite a game here,” he muses. “I think they’ve managed to make robotics appealing to a more general audience, which is hard to do.”