China’s reality TV programming is being taken over by robots and AI

Almost two decades ago, Wang Xi, then a teenager living near the Chinese capital of Beijing, fell in love with an American robot combat TV show called BattleBots. One of the most-watched TV shows ever in the US, it got 1.5 million viewers per episode at its peak, and was syndicated around the world, including China.

Almost two decades ago, Wang Xi, then a teenager living near the Chinese capital of Beijing, fell in love with an American robot combat TV show called BattleBots. One of the most-watched TV shows ever in the US, it got 1.5 million viewers per episode at its peak, and was syndicated around the world, including China.

Wang knew then that he wanted to one day make his own robot, and having it battle on TV in China. This year, Wang saw his dream realized on China’s first robot combat show, King of Bots (铁甲雄心), which debuted in January. It’s one of a series of robot combat shows that will air in the country this year, after China saw its first offline robot battle tournaments in recent years.

Wang’s robot, Greedy Snake, fought robots made by other teams from China, as well as from the UK and the US. The show, which aired on the widely-watched Zhejiang TV channel, quickly became popular. Its Feb. 26 episode ranked in the second spot for entertainment shows across 52 cities in its time slot, behind a Chinese remake of a trivia competition, according to research firm CSM (link in Chinese).

Wang, who was working as a game developer, is now a technical consultant to the show, said the show was inspired by the revival of BattleBots, starting in 2015. But China’s promotion of itself in recent years as a nation at the forefront of technology and innovation likely played a role too.

Popular Chinese reality TV shows have often been dominated by singing or dance competitions. In 2017, one of China’s most popular TV reality shows, The Rap of China, garnered a combined 2.7 billion views for the season and turned dozens of young contestants into stars, while another widely watched show focused on reciting classical Chinese poetry. The robot shows represent a change for reality TV programming, and come as China seeks to advance its technological prowess, from vowing to be a leader in artificial intelligence in 2030 to investing more in industrial robots for automation. Last year, a show that had humans compete against AI technologies in a variety of challenges—such as facial recognition—debuted in August.

While King of Bots had its season finale Monday (March 5), later this month, iQiyi, a streaming-service giant backed by China’s search giant Baidu, is planning to air a similar show called Clash Bots on March 23. Youku, another online video platform backed by Alibaba, is also rolling out This is Bots later this year, though a date hasn’t been set yet. The companies didn’t reply to queries about the programs from Quartz.

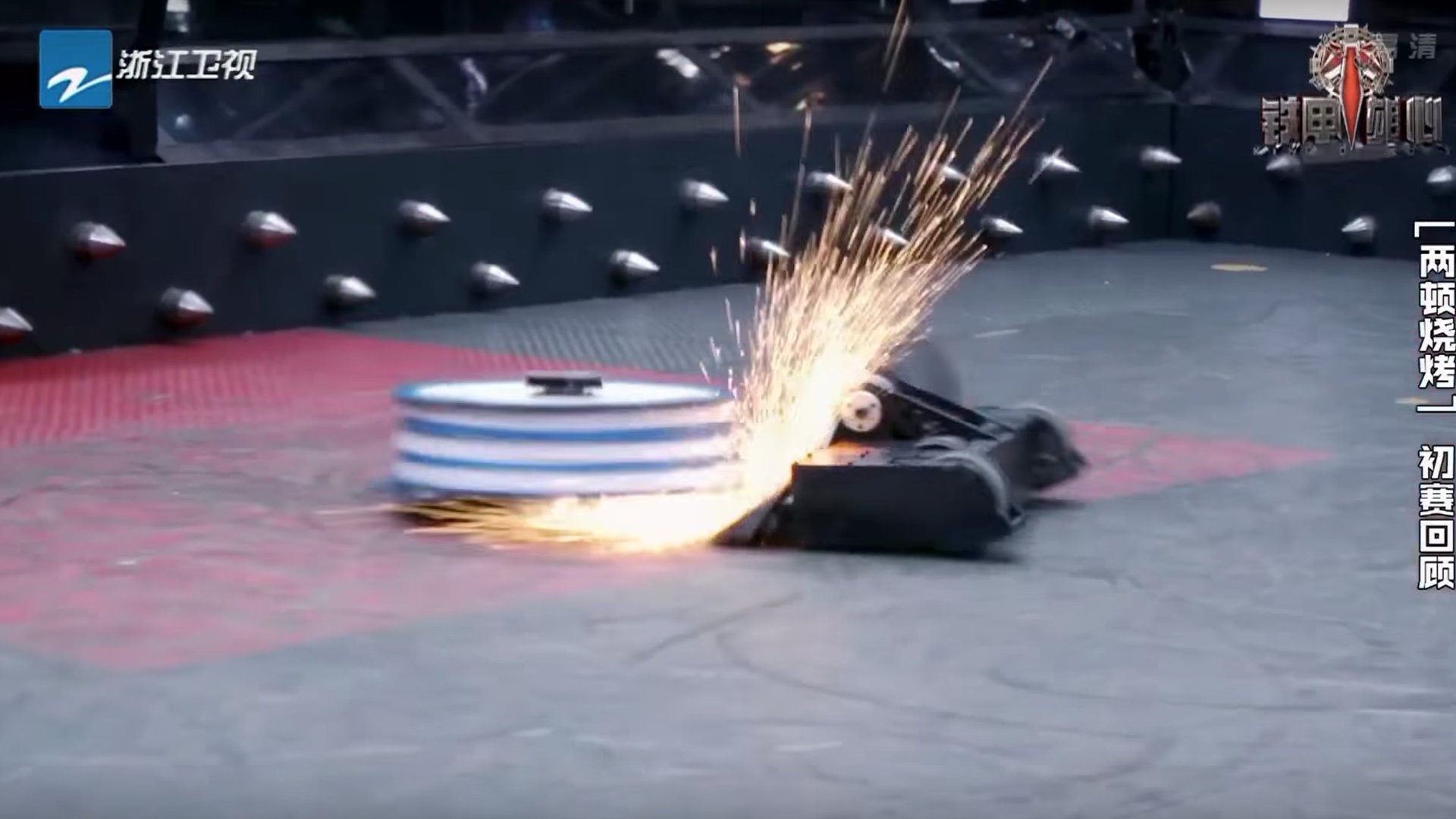

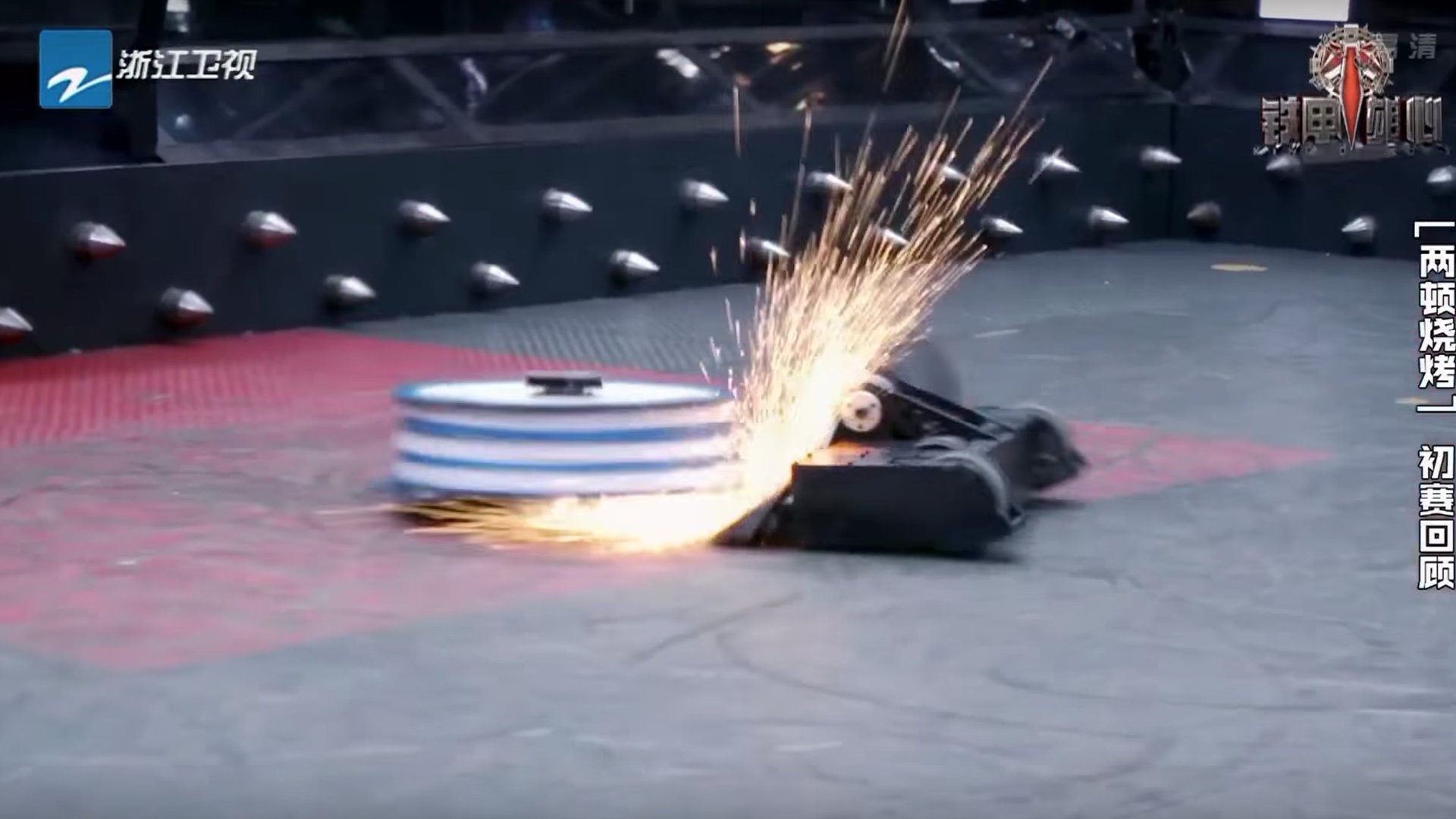

In King of Bots, competitors pit remote-controlled bots against each other in a container made of bulletproof glass. During a three-minute fight, each team needs to try to paralyze the other’s machine in order to win the game. Participants also need to navigate their bots to dodge traps in the competition stadium, including rivets on the wall, flames that burst from the ground, serrated rollers, and flipping platforms.

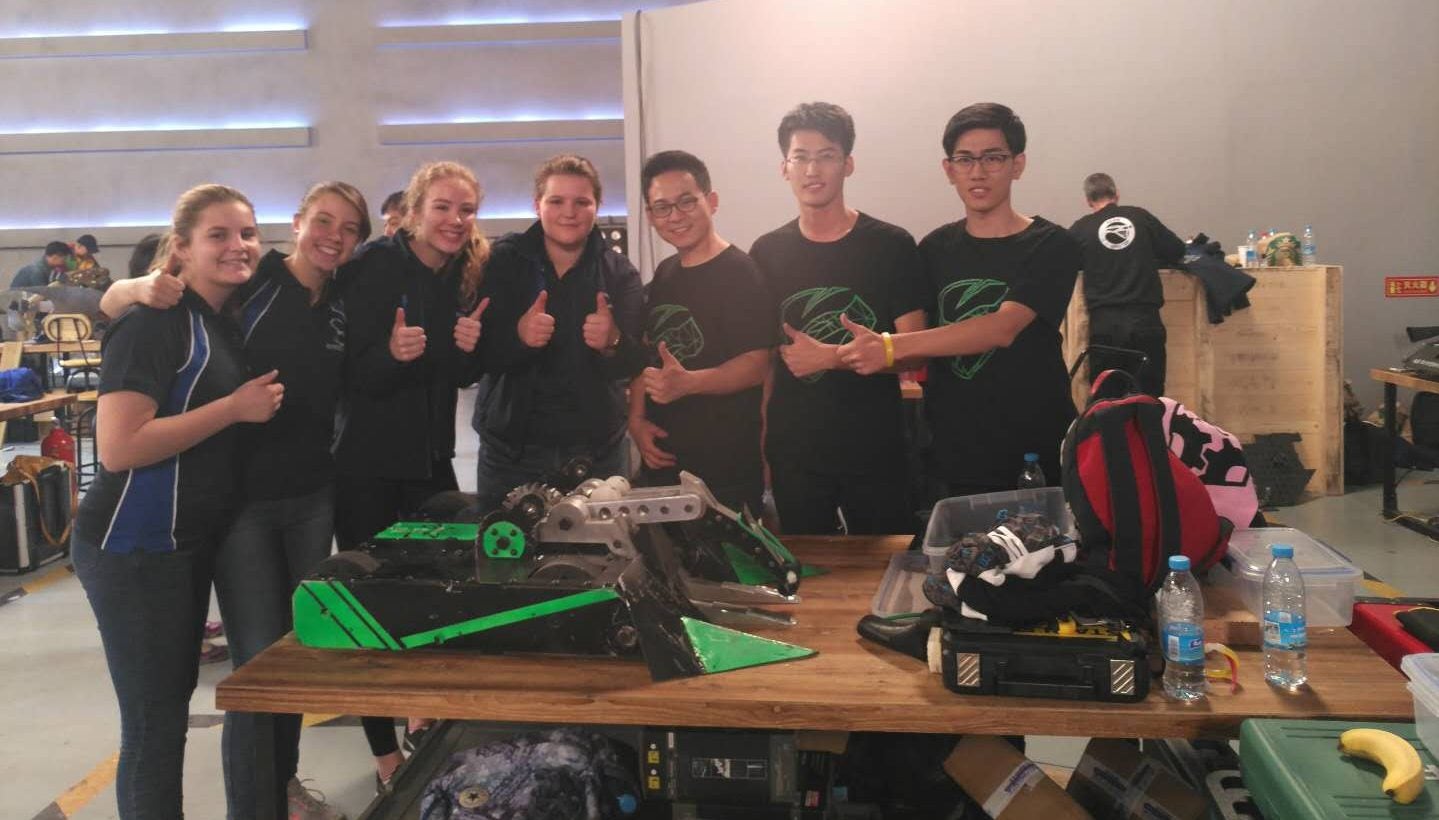

Competing teams, including those from the UK, the US, and Australia, all received a handsome amount of financial support from the show. In Wang’s case, he received some 200,000 yuan ($32,000) to make his bot, a tanker-like 110-kilogram (242 lbs) machine (on left, photo below) that lifts its opponent and hurls it down. The team, which included his wife, spent six months designing the robot, which was manufactured in Shanghai.

A total of 48 teams (link in Chinese) participated. Wang said he found the foreign teams more experienced in combat strategy and design because countries like the UK and the US have a longer history in robot combat events than China. Wang’s bot lost in the competition for one of the top eight spots to another Chinese team.

Yet, he notes, the show provided a platform for people obsessed with making robots, and a way to gauge their skill level. “If a country wants to rejuvenate and even lead the world, we should be counting on the attitude of pursuing knowledge and science,” Wang said.

Before the TV show, most teams were only competing offline, said Wang, who founded China’s biggest robot combat association in 2015. Now the group has more than 1,000 members. Wang estimates that there are around 300 people skilled enough to make a robot capable of competing and fighting.

One of them might be Yue Tan, an electronics engineering major in southern Guangdong province, who is making a 13.6-kilogram (30 lbs) bot that he hopes will compete in an offline competition hosted by the show’s co-producer, Shanghai-based video firm The Makers, starting in May. “Children can explore and build up confidence through making robots. Even if you fail, you will learn to improve during the process,” says Yue, who’s been discussing robot-making tips on Zhihu (link in Chinese), China’s answer to Quora.

Others also believe that the TV shows can encourage innovation. Chen Wei, the producer of iQiyi’s upcoming Clash Bots, expects that the show will boost young people’s aspirations for Chinese manufacturing and technology. “China is still lagging in some industry sectors,” Chen told news portal Chinanews. “If the game becomes popular and more people get inspired by it, our technology will probably also improve.”

The Chinese robot makers may have a ways to go. While two Chinese teams made it to the quarter-finals, a team from the UK (link in Chinese) eventually won the competition and half a million yuan (nearly $79,000) in prize money in the season finale.