Lowering air pollution just a bit would increase life expectancy as much as eradicating lung and breast cancer

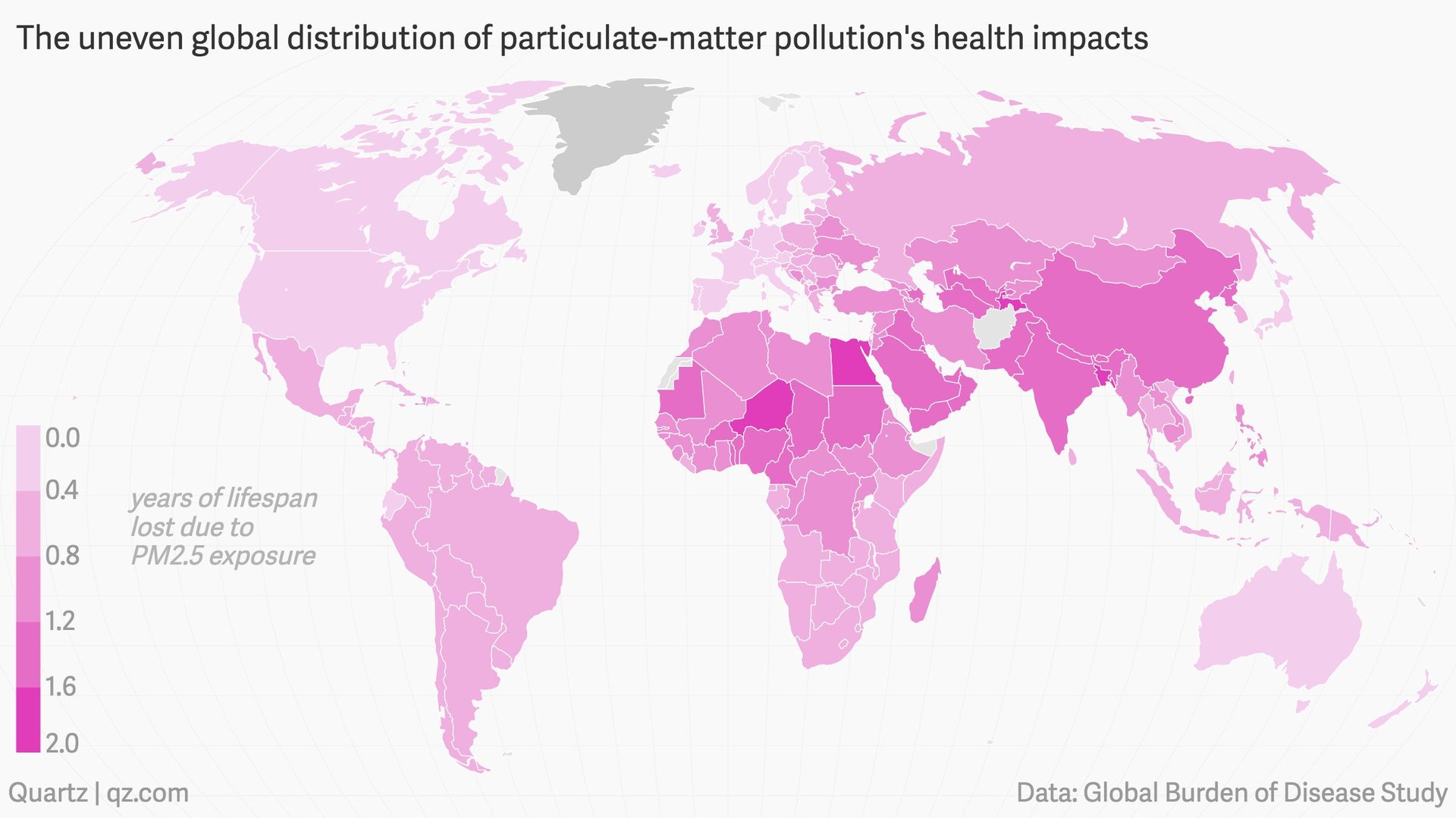

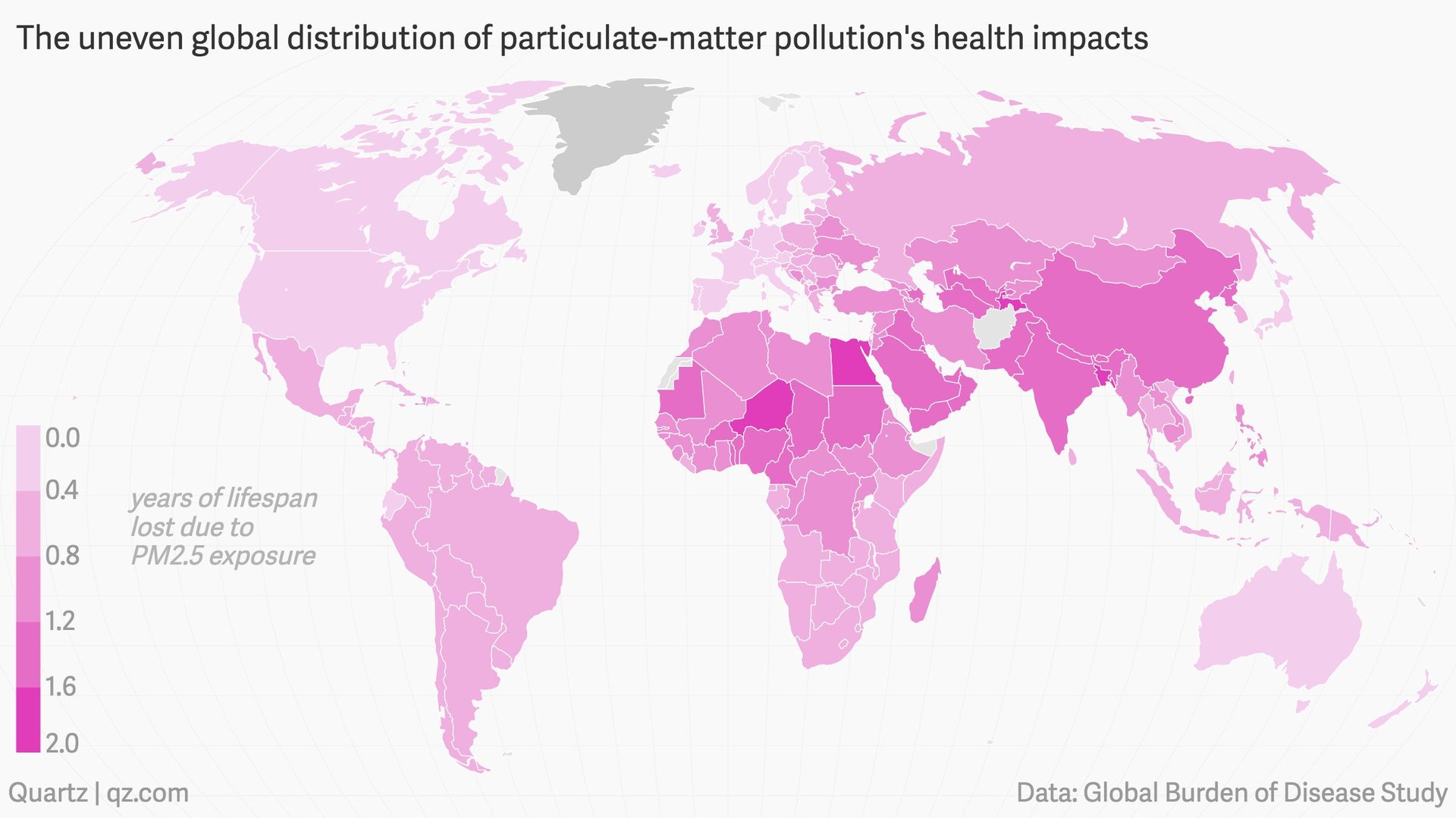

Exposure to a prevalent type of air pollution—particulate matter called PM2.5—takes one year off the average global lifespan, according to research published Wednesday (Aug. 22) in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters. But that air pollution is not evenly distributed; for people living in the most-polluted areas of Asia and Africa, the situation is worse—life expectancy for them drops between one year and two months to one year and 11 months.

Exposure to a prevalent type of air pollution—particulate matter called PM2.5—takes one year off the average global lifespan, according to research published Wednesday (Aug. 22) in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters. But that air pollution is not evenly distributed; for people living in the most-polluted areas of Asia and Africa, the situation is worse—life expectancy for them drops between one year and two months to one year and 11 months.

What’s more, simply reducing global PM2.5 air pollution to levels recommended by the World Health Organization would be the equivalent of globally eradicating breast and lung cancer in terms of life spans.

PM2.5 is released from tailpipes of vehicles, coal-fired power plants, and industrial plants of all kinds. Events like dust storms and wildfires produce large amounts of the particulate matter, too.

Right now, 95% of the global population are exposed to levels of PM2.5 that exceed the WHO’s recommended level, the authors write.

The researchers from the University of Texas, University of British Columbia, Brigham Young University in Utah, Imperial College London and the Boston-based Health Effects Institute used a massive data set known as the Global Burden of Disease Study, which includes more than 1 billion data points on the health and mortality of people in all 195 countries on Earth. The data in the most recent edition of the study, and the one used by the researchers, was published in 2016 and covers 1990 to 2015.

The life-expectancy findings build on a previous study using the same data, in which researchers found that exposure to PM2.5 was the fifth-highest mortality risk factor in 2015.

Exposure to PM2.5 caused 4.2 million deaths that year globally, and the loss of 103.1 million life-years, after adjusting for disabilities. That was the equivalent of 7.6% of all deaths worldwide that year.

That study also found that death rates from air pollution had increased: They calculated 3.5 million people died globally from breathing PM2.5 in 1990—700,000 fewer people than were killed by the same type of air pollution in 2015. That uptick, the researcher wrote, was likely “due to population ageing, changes in non-communicable disease rates, and increasing air pollution in low-income and middle-income countries.”