Not “adequately reconciled”: What blocked the BAE-EADS merger

Had it come into being, the world’s largest defense and aerospace company would have been a fascinating experiment in transnational joint ownership and the mixing of business interests with national-security imperatives. But hours before a UK regulatory deadline, merger talks between Britain’s BAE and the Franco-German EADS were called off. What was the problem? Irreconcilable national interests.

Had it come into being, the world’s largest defense and aerospace company would have been a fascinating experiment in transnational joint ownership and the mixing of business interests with national-security imperatives. But hours before a UK regulatory deadline, merger talks between Britain’s BAE and the Franco-German EADS were called off. What was the problem? Irreconcilable national interests.

In a published statement the companies said:

Notwithstanding a great deal of constructive and professional engagement with the respective governments over recent weeks, it has become clear that the interests of the parties’ government stakeholders cannot be adequately reconciled with each other or with the objectives that BAE Systems and EADS established for the merger.

Even though the deal is dead, it’s worth shedding light on the political resistance that won out over the cost savings and competitive advantages the two companies say they would have had by merging.

Let’s start with France. France had a 15% stake in EADS, which it had agreed to dilute to 9% in the merged company. The French wanted to reserve the right to acquire a larger stake in future, however. Meanwhile, the Germans said they wanted what the French had in terms of shareholdings, but also wanted the headquarters of the combined entity to be in Germany. The merger plans placed the defense operations headquarters in Britain and those of the commercial jet making part, Airbus, in France.

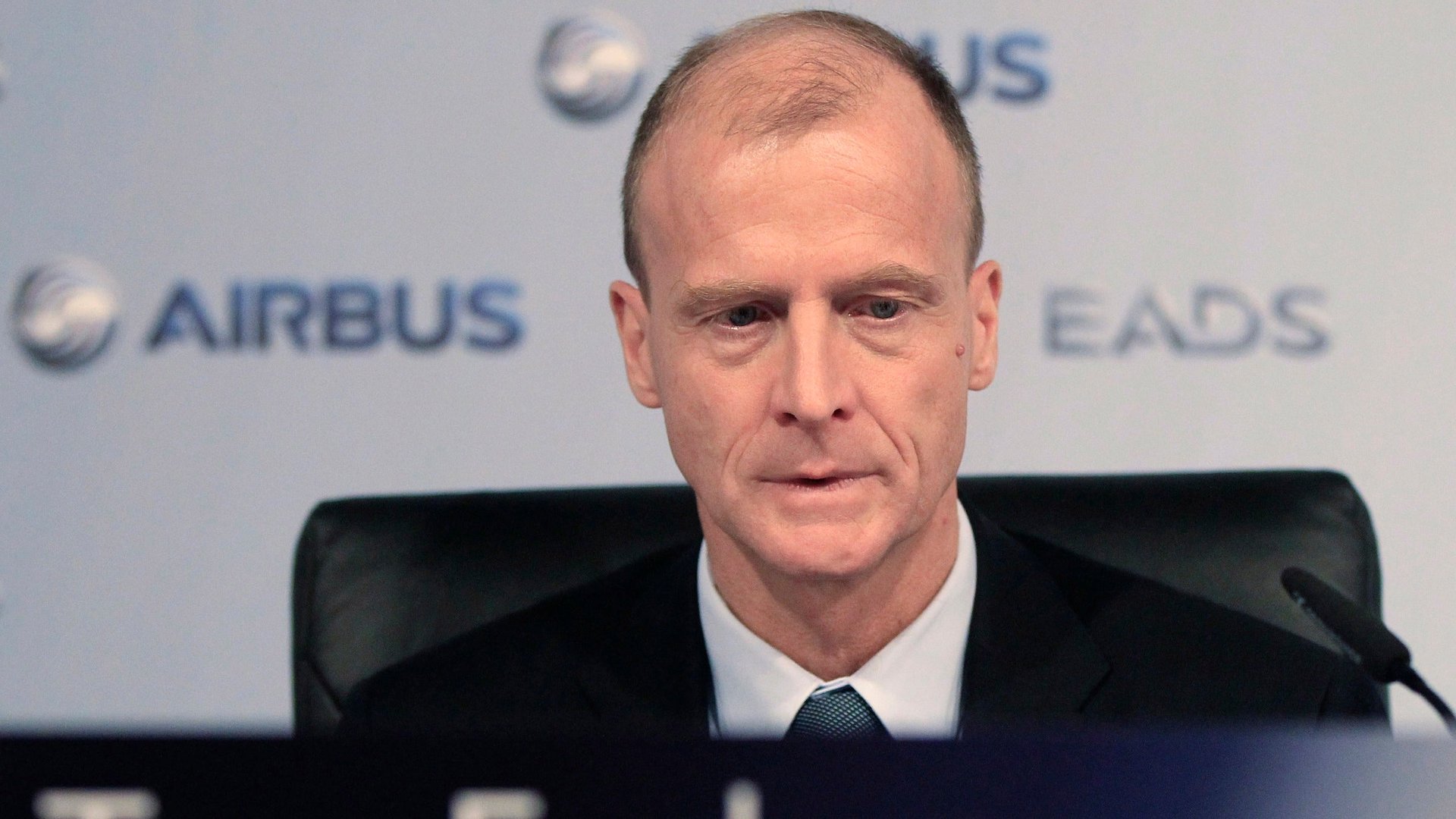

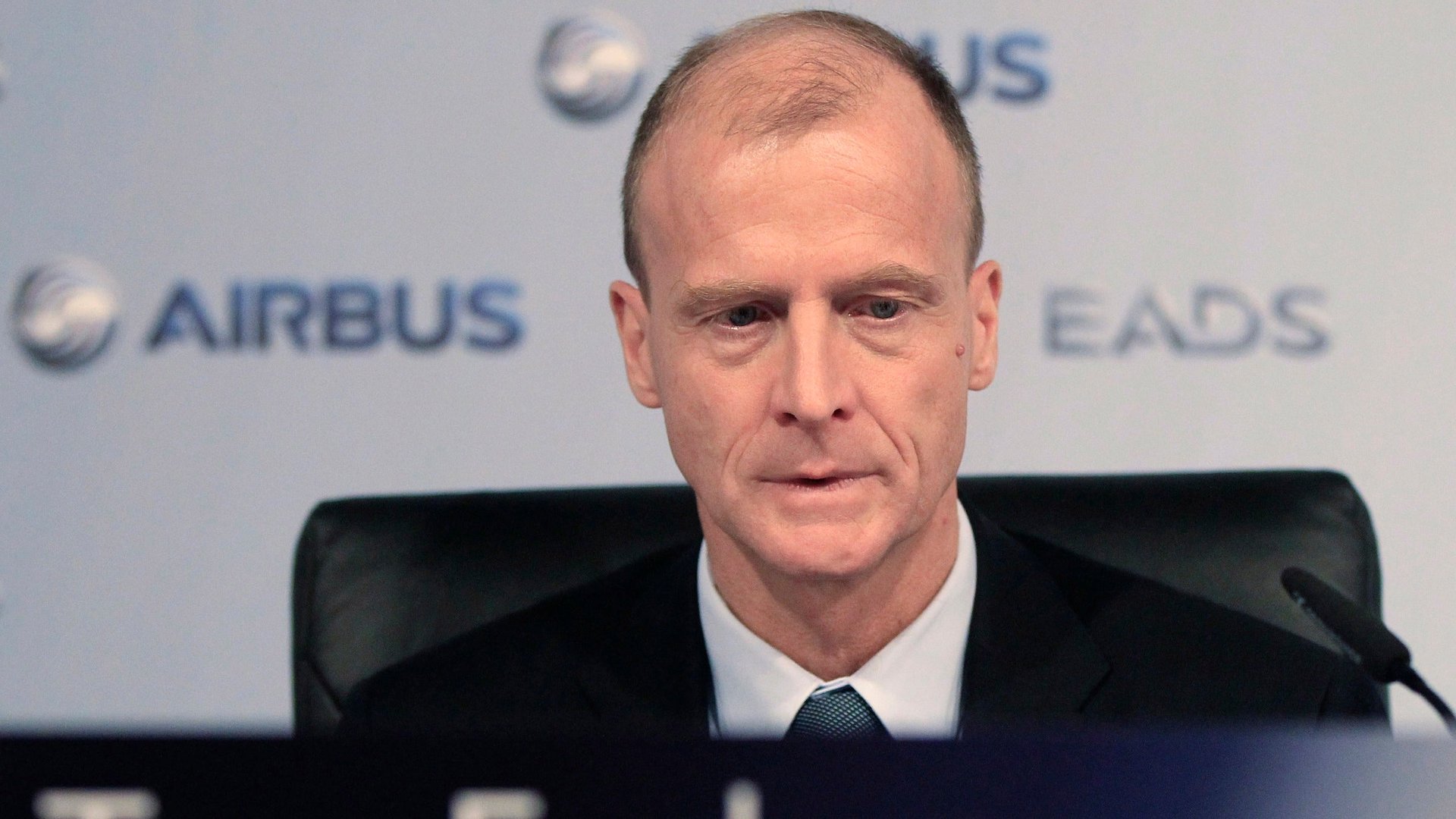

Nothing for Germany, save a German chief executive, Tom Enders. He would have run the company but eventually chief executives move on. Last night it emerged that German Chancellor Angela Merkel wasn’t convinced by the deal anyway, and had reservations about merging the two industries.

Then there were UK concerns. The British government has what is called a “golden share” in BAE, giving it veto power if national interests are at stake. The British defense secretary said that the UK would not back the deal without written commitment from France and Germany that shareholdings be capped in size and their influence be curtailed to preserve BAE’s strong business relationship with the US Pentagon.

The UK also did not want France and Germany to vote as a bloc. Another big sticking point reportedly was an insistence by the UK and the two company leaders that directors appointed by France, Germany, and Britain wouldn’t serve on the top board. All of this said, the UK generally backed the deal, which would have protected EADS jobs in the country.

The US had its say too, demanding holdings by the French and Germans be limited to 10% or less. Mostly concerns were about security—who has access to what—and influence over the new company by France and Germany. BAE works on classified US military research and development projects.

Shareholders had yet to be asked what they thought. Governments had to give a green light first. If shareholders were asked, though, the answer would have been mixed. On Monday, Invesco, the largest shareholder in BAE, issued a statement questioning the strategic and financial logic of the proposed $45 billion merger. Soon after, other investors followed suit with 30% of shareholders expressing serious concerns (paywall), though no one said they would block the deal.

It’s impossible to pinpoint any one disagreement that scuttled (or scuppered) the deal; and with so many stakeholders, perhaps it was just too complex to pull off. Or perhaps it’s just that the world is not ready yet for shared ownership of military secrets.