Trump’s denial of the Puerto Rico death toll does not belong in a democratic conversation

On Sept. 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico. It ravaged the island, and killed 16 people, according to the official death count. But thousands more Puerto Ricans died over the following months due to systematic failures, including a lack of electricity and health care.

On Sept. 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico. It ravaged the island, and killed 16 people, according to the official death count. But thousands more Puerto Ricans died over the following months due to systematic failures, including a lack of electricity and health care.

After downplaying the death toll for nearly a year, the Puerto Rico government released a revised official estimate on Aug. 28, setting the number of casualties connected to the hurricane at 2,750. Other estimates have put the number much higher, at nearly 5,000.

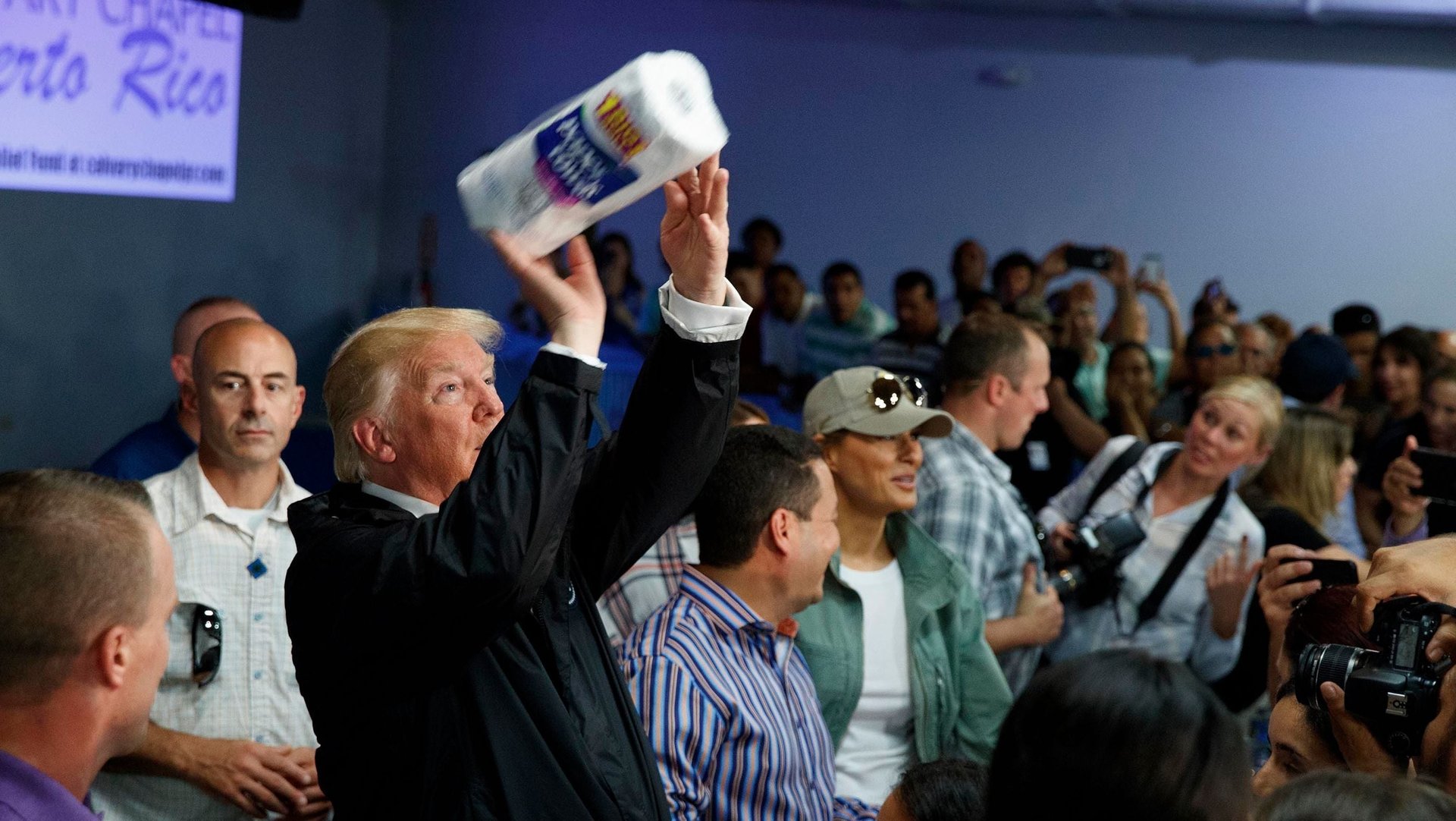

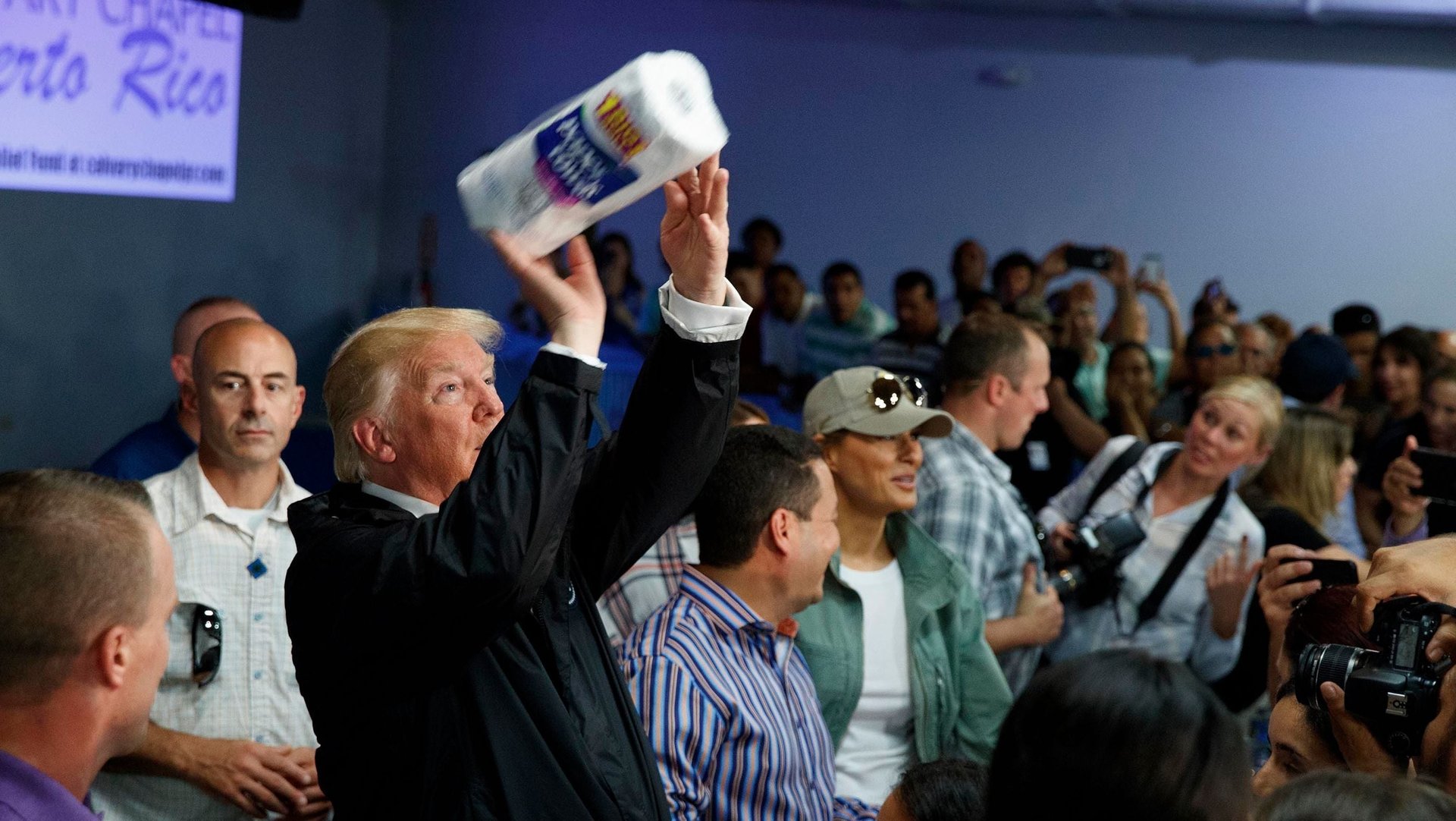

US president Donald Trump, who called Maria disaster-relief efforts “an incredible, unsung success,” denies those numbers. On Sept. 13, Trump tweeted that ”3000 people did not die in the two hurricanes that hit Puerto Rico” and accused Democrats of inflating the death count to make him look bad. The statement was so outrageous that even the president’s allies pushed back. “There is no reason to dispute these numbers,” said House speaker Paul Ryan, adding that the high death toll was due to the storm hitting “an isolated island, and that’s really no one’s fault.”

Though Trump and Ryan are both deflecting blame, the president’s outright denial of thousands of deaths is far more sinister. He’s taking a page straight from the authoritarian playbook.

“Given how easily this president denies the truth, this is just one more lie to him,” says Federico Finchelstein, a history professor at the New School in New York who studies populism and dictatorship. Finchelstein says there are at least two elements of Trump’s statements that fit into a populist framework: his consistent dehumanization of minorities—in this case Latinos—and his view of himself as the foremost authority on pretty much everything.

When Trump denies the death of Puerto Ricans, Finchelstein says, he is essentially denying their importance as humans. (By calling Puerto Rico an “isolated island,” Ryan is doing the same, albeit with more subtlety.) Trump “does not consider these minorities equal,” Finchelstein says. “On the contrary, they are used as a tool of his ongoing campaign mode.”

Dehumanizing minorities—something Trump has consistently done as a candidate and president—is a quintessential authoritarian technique to foster popular support by creating a scapegoat—Jewish people in Nazi Germany, refugees in today’s Italy or Hungary—to blame for the country’s problems.

Trump’s lies about Puerto Rico’s death toll are particularly insidious because of the frame of reference they evoke. It “sounds like dictator talk,” Finchelstein says. “One can imagine Pinochet saying this, or the [Argentinian]junta militar,” referring to the dictatorial regimes of Chile and Argentina in the 1970 and 1980s, which killed citizens with impunity, all while denying them. Argentina’s denial of those deaths during its so-called “dirty war” on political dissidents was so commonplace, its victims gained the nickname of “desaparecidos,” the disappeared, because they would vanish without any official confirmation of their deaths.

Trump’s latest outburst continued yesterday (Sept. 14) with tweets questioning the research that led to the current estimates. (“How would they know this?” Trump asked in a tweet.) It sets a dangerous precedent, for denying human lives is not the same as denying the size of the crowd at your inauguration ceremony. It shows that the president would literally choose to go over the dead bodies of his country’s citizens than assume responsibility for his government’s mistakes.

“What Trump said does not belong in a democratic vocabulary,” Finchelstein says. “He is clearly not a dictator, but he is bastardizing what a democratic presidency should be.”