Economists figured out the best way for Uber to say sorry

In January 2017, John List, an economist at the University of Chicago, had a very bad Uber ride. List had called the Uber to get to a conference in downtown Chicago, where he was supposed to present a paper. The trip, List says, wound up being a “whirlwind tour” of Chicago and taking twice as long as it should have.

In January 2017, John List, an economist at the University of Chicago, had a very bad Uber ride. List had called the Uber to get to a conference in downtown Chicago, where he was supposed to present a paper. The trip, List says, wound up being a “whirlwind tour” of Chicago and taking twice as long as it should have.

List wasn’t just any aggrieved rider. He was also Uber’s chief economist, and he took his complaint straight to the company’s CEO. “I called Travis [Kalanick] and I told Travis, ‘I will never use your app again because I got this terrible trip,’” List says. “And I said, ‘To compound the bad trip, I haven’t even received an apology from Uber.’ And he said, ‘Well, we’ll get to that, and why don’t you work on it?’”

The result, a working paper (pdf) titled “Toward an understanding of the economics of apologies,” is due out in the National Bureau of Economic Research this month. In it, List and three collaborators, all but one of whom are affiliated with Uber, analyze an experiment involving 1.5 million Uber riders to determine if and how the company should apologize when a customer has a bad experience.

List and his co-authors define a “bad ride” as one that arrives at its destination later than the ETA provided by Uber. Company data showed that riders whose bad rides arrived more than 5 minutes late tended to spend 5% to 10% less on Uber in the future than would otherwise have been expected. In other words, people who have bad experiences on Uber are less likely to take Uber again.

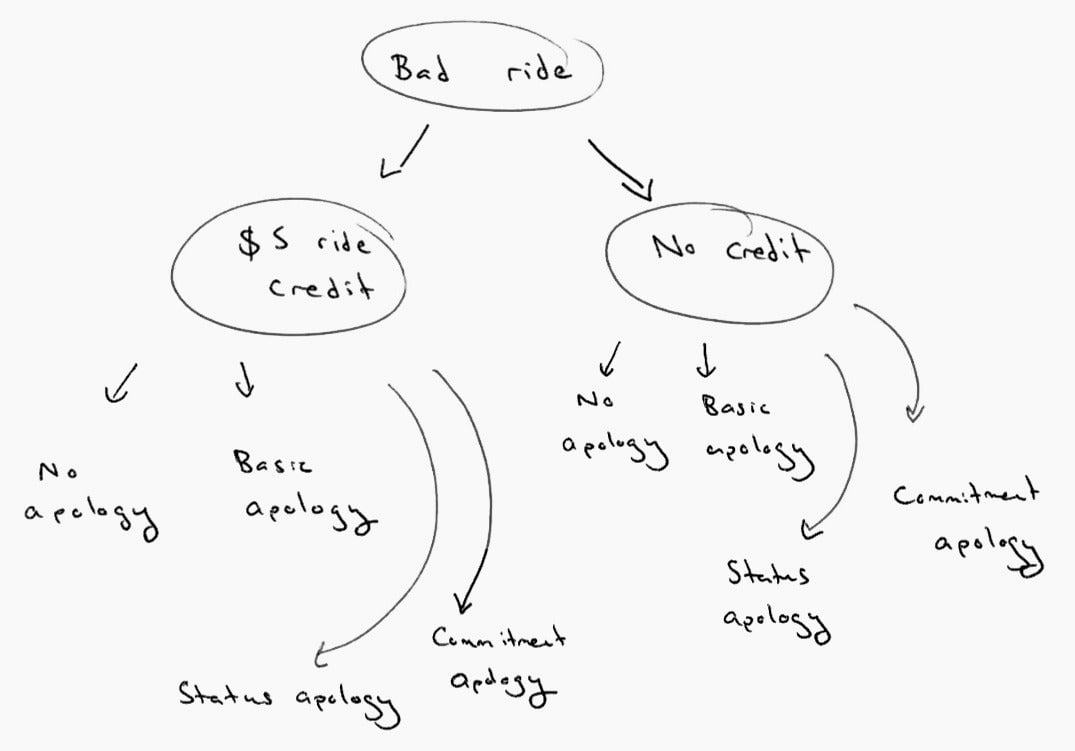

How could Uber mitigate this? From June to October 2017, List’s team tested eight possible responses on 1.5 million US riders whose “bad” trips dropped them off 10 to 15 minutes late. The responses came via email within an hour of the trip ending, and combined a possible financial remedy (a promo code for $5 off a future ride) with one of four written apology options, described in the paper as follows:

- No apology

- Basic apology, e.g., “Oh no! Your trip took longer than we estimated.”

- Status apology, e.g., “We know our estimate was off.”

- Commitment apology, e.g., “We’re working hard to give you arrival times that you can count on.”

You can visualize that with this beautiful apology flow chart I drew:

The economists spent a couple months sending Uber riders these apology notes, and sometimes a $5 ride coupon, and they found that… people like getting free rides! “Our principal finding is that it is primarily a promotional code that can be used for a future trip that restores the firm’s reputation and not the apology itself,” they write. Rider satisfaction was measured by a slight increase in net spending after receiving an apology with a promo code. Apologies were more effective for rides that were either a little late or very late, and least effective for moderate lateness, where the rider was most likely to blame Uber for the bad experience.

That was also only for the first bad ride. For a second and third bad ride, an apology with a promo code could actually have a negative effect on future spending. The economists said this “backfire effect” was consistent with consumers perceiving each apology as a promise of improvement, only to be let down by Uber again.

The results are strikingly similar to the findings of a February 2018 paper from researchers at NYU and Via, a ride-hail app that operates in New York, Chicago, and Washington, DC, with exclusively shared rides. In that experiment, the researchers considered how best to compensate several thousand “frustrated” riders who were picked up at least 8 minutes later than Via estimated in New York and DC (the Uber paper, remember, dealt with late drop-offs). They tried compensating the frustrated riders in the following ways (my paraphrase):

- Control: no compensation

- Communications: riders received a text message from Via to apologize for the inconvenience, but no financial compensation

- Credit: riders received a $5 credit for future rides

- Waived: charges for the ride were refunded to the rider

Each rider received their “compensation” in a text message from Via. The researchers found the $5 credit was “significantly more effective” at getting customers to spend more on Via in the future than either a text apology or waiving the charge for the ride, as “providing a credit value offers an opportunity for the rider to use the service again.”

The $5 credit also turned out to be revenue positive for Via, as frustrated New York riders who got a promo went on to spend 12% more, on average, and frustrated DC riders 37% more, also on average, than frustrated riders in those cities who weren’t compensated in any way for their late pickups (the control group). Both the Uber study and this one also found that a $5 promotion timed to a bad ride experience was more effective at keeping customers happy and spending more than a random or generic $5 promo.

An earlier version of this post was published in Oversharing, a newsletter about the sharing economy. Sign up here.