Luxury labels are going direct-to-consumer

The idea of selling fashion straight to shoppers sounds simple enough, but how often it happens today represents a big shift in retail. For decades, retailers that collected brands under one roof were industry power brokers, playing a lead role in determining which labels shoppers bought, or even knew existed, and helping to shape their images. Plenty of labels had their own stores, but establishing a global network of shops to reach all potential customers could be prohibitively expensive and complicated. Many brands, especially in luxury fashion, instead relied on multi-brand retailers to be their main connection to shoppers.

The idea of selling fashion straight to shoppers sounds simple enough, but how often it happens today represents a big shift in retail. For decades, retailers that collected brands under one roof were industry power brokers, playing a lead role in determining which labels shoppers bought, or even knew existed, and helping to shape their images. Plenty of labels had their own stores, but establishing a global network of shops to reach all potential customers could be prohibitively expensive and complicated. Many brands, especially in luxury fashion, instead relied on multi-brand retailers to be their main connection to shoppers.

But thanks in large part to the growth of e-commerce and social media, brands are able to connect—and sell—directly to customers themselves (pdf), shifting the balance of power between the brands and retailers. Those leaning into this shift aren’t just digitally native upstarts like Everlane, Bonobos, and others that built their businesses on the idea of cutting out the middleman. Labels across the spectrum are doing it, through a combination of e-commerce and their own stores, up through and including top luxury labels. (Sorry, they’re still charging the same retail prices so as not to undercut those wholesale partners who are still important.)

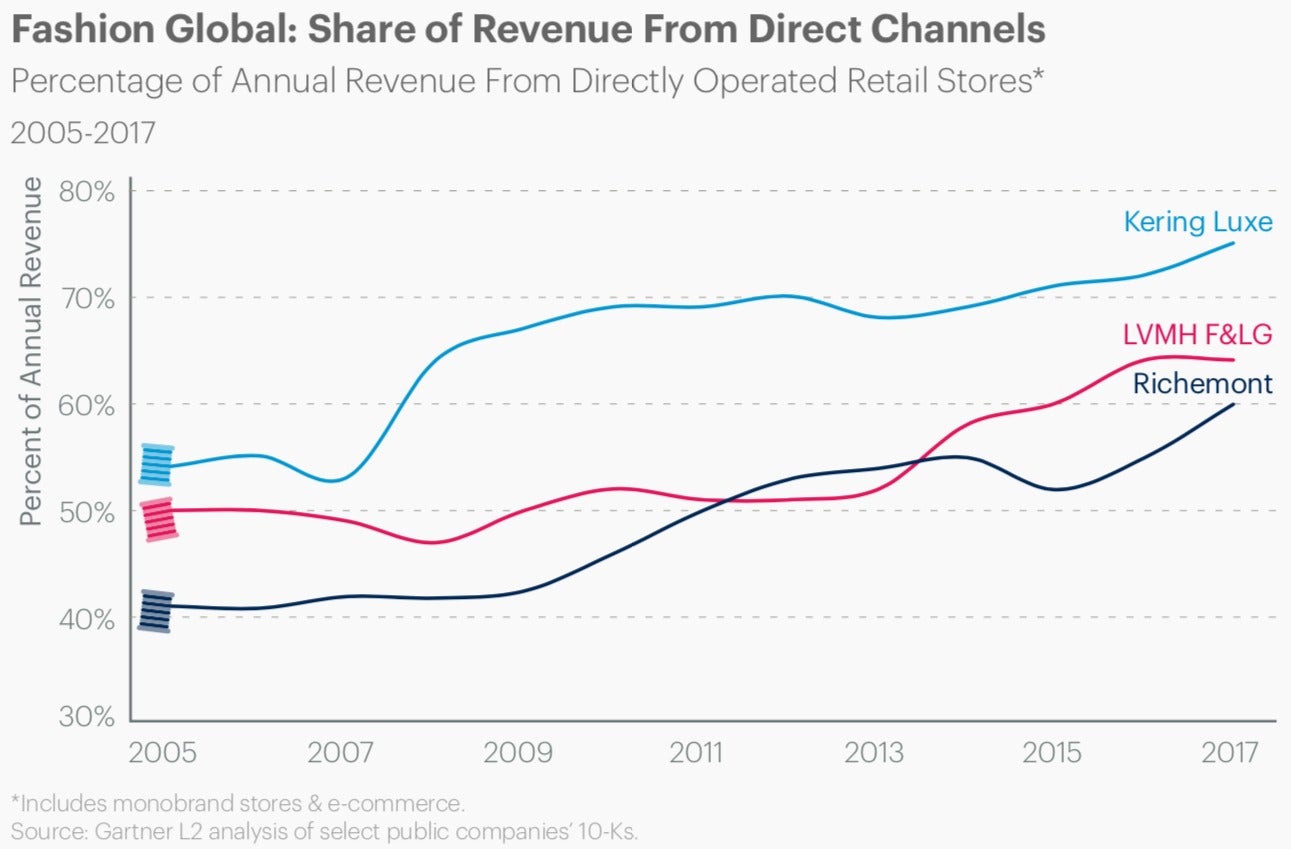

According to an analysis of financial filings from LVMH, Kering, and Richemont—three of the world’s biggest luxury conglomerates—by Gartner L2, a business-intelligence firm, the companies have substantially increased the percentage of annual sales they get from their brands’ directly operated stores and e-commerce over the past decade. Their brands include names like Louis Vuitton and Celine (LVMH); Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Balenciaga (Kering); and Cartier, Azzedine Alaïa, and Chloé (Richemont).

The numbers are notable given that luxury was notoriously slow in embracing digital sales. “They’ve been some of the longest holdouts on really just having a [business-to-consumer] business,” says Lauren Price, director of client strategy for luxury and specialty retail at Gartner L2. A decade ago consumers were still proving that they would buy high-end products like a $5,000 dress online, and brands were unsure how to replicate their high-touch store experiences on a website, let alone one viewed through a smartphone.

But the investments they made years ago in their digital businesses are increasingly paying off, leading brands to keep building out their operations, Price says, and while stores still account for the great majority of direct sales, e-commerce is driving a lot of the growth.

There are numerous benefits for luxury brands doing more of their sales straight to shoppers, whether those transactions happen in stores or online. They have more control over how a product is presented, the story around it, the images and description of it, and what items it’s next to—all critical components in projecting a high-end image. The margins are also better, since a retailer isn’t taking a cut of the sale. Not least, brands get direct access to a rich array of customer data that they don’t typically get from wholesale partners.

Direct sales do come at a cost. Brands must maintain stores and websites, plus handle logistics and all those costly returns. Price points out that it isn’t enough to just build an e-commerce shop and expect people to find it either. They have to pay for ads and other ways of driving traffic.

But to brands, the returns are worthwhile. “The reason why we’ve developed a bigger direct-to-consumer business is because it’s critical today to have a customer understand you, inside and out,” Theory CEO Andrew Rosen told Glossy recently (paywall). “We simply can’t do that in the same way with outside retailers, whether it’s Saks or Neiman or Bergdorf.”