In an age of super-fast fashion, Mexico and Turkey may be the new China

Fashion’s global supply chains run thick and fast through China. It’s by far the world’s biggest clothing exporter (pdf), a status it acquired by being quick, reliable, and inexpensive, and has for decades offered many big brands the most cost-effective option to produce their clothes.

Fashion’s global supply chains run thick and fast through China. It’s by far the world’s biggest clothing exporter (pdf), a status it acquired by being quick, reliable, and inexpensive, and has for decades offered many big brands the most cost-effective option to produce their clothes.

But shifts now taking place in China and across fashion could eventually redraw the world’s garment-manufacturing map. A new report by the management consultancy McKinsey finds that rising costs in China and the imperative for fashion brands to deliver goods faster than ever are making it more cost-effective for Western brands to produce their simple styles in low-cost countries nearer at hand. For brands selling in the US, that primarily means Mexico, while Turkey has emerged as a prime manufacturing destination for labels selling in Europe.

The case for nearshoring

In 2005, labor costs in China were about one-tenth what they were in the US, according to McKinsey. Today they’re about one-third. The rise has made it so that labor in some “nearshore” countries is not much more expensive—or possibly even cheaper—than in China, the report says.

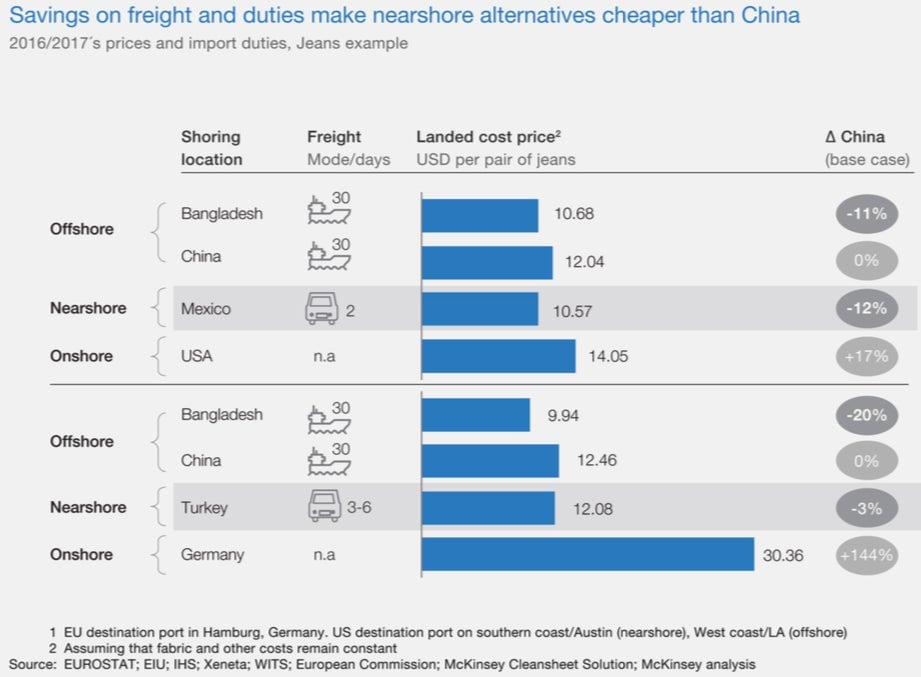

Add in savings on freight and duties for countries closer at hand, and nearshoring becomes an even sweeter deal. The firm calculated the cost to produce a basic pair of jeans and import it into either the US or Germany, using the sum to do the work in China and ship from there as a baseline. To make the same pair of jeans in Mexico and import them into the US would cost 12% less. For a company looking to import its jeans into Germany, Turkey was 3% less expensive than China.

That wasn’t the cheapest option: To produce in Bangladesh cost 20% less than China. But Turkey and Mexico pulled much further ahead when factoring in the much shorter delivery times from those countries—just a few days, versus a full month if a brand manufactures in China or Bangladesh. The shorter lead times yield a number of benefits, creating an added economic bonus. As McKinsey explained:

As a company gets items into stores faster, it will be able to test and scale more styles. Not only will it be able to boost sales volumes and sell-through rates, but the company can also reduce inventory levels and mitigate the brand dilution resulting from markdowns and clearances.

Nearshoring economics, therefore, become even more attractive when considering the higher full-price sell-through rates, which the faster fashion model enables. Our analysis suggests that a 5-percentage-point increase in sell-through would make up for the higher labor costs. Costs are equalizing, even in shifts from low-cost countries, such as Bangladesh, to nearshore markets.

The picture looked still rosier when McKinsey added automation into the mix. Fashion lags way behind other industries in implementing automated manufacturing, but companies are starting to embrace new technologies in their efforts to speed up. McKinsey assumed a hypothetical scenario where all major technologies currently in development were implemented, and worked with a university in Aachen, Germany, and the Digital Capability Center Aachen to calculate the cost savings in time and labor for producing a pair of jeans.

Based on their calculations, to produce the jeans in China with automation and import them into the US, the final cost ends up being around $11.40. But to produce them in Mexico with automation and import them into the US, the cost would be about $10, plus the assorted benefits of the shorter lead time, too.

Not so fast

All this sounds great, but putting it into practice isn’t always so simple. Karl-Hendrik Magnus, a McKinsey partner and apparel industry expert, presented the report at an Oct. 11 summit held by Sourcing Journal, a trade publication focused on fashion’s supply chain. On a panel with him was Colin Browne, Under Armour’s chief supply chain officer.

“I’m not a believer in that whole ‘rainbows and unicorns’ kind of effect of this,” Browne said. “It’s not all going to change overnight.”

Still, the experts agreed that these changes are coming, and to some degree have already begun. They’re just likely to take a long time. For starters, China has built up a manufacturing infrastructure and capacity that other countries just can’t match. Some brands are already moving a share of production to nearby countries, but a large-scale shift might not be possible until those countries are able to build up factories to handle the workload.

Probably the biggest holdup, though, isn’t among the suppliers doing the work of stitching together finished products. It’s the “tier 2” suppliers making the actual textiles. The vast majority of that work currently happens in Asia, particularly in China, especially in the case of any specialized fabrics, like those athletic brands use. Companies may want to assemble finished garments in Mexico or Turkey, but they still have to buy and import all their materials from much further overseas. With shipping costs and duties to take into account, many Western brands are likely to keep their production in Asia rather than move it nearby.

“Certainly from an Under Armour point of view, because of the specialized materials we use in much of our apparel, unless we have really good tier 2 suppliers within region, it becomes really difficult to do that,” Browne said.

As for automation, Erika Swan, Reebok’s vice president of product operations, pointed out that Asia’s giant clothing manufacturers aren’t sitting idly by. They’re investing heavily in automation to stay competitive as their labor costs rise. It’s possible that production will see a big shift west in the next few years, but it’s “not a slam dunk,” she said.

And as McKinsey notes, many basic processes still can’t be fully automated. That includes sewing, which is the most labor-intensive part of making most garments. Labor-intensive production in offshore countries, the report states, “is not going away anytime soon.”

Still, pressure is growing

Even so, forces are gathering that are pushing clothing and footwear brands to look outside of China and nearer to home for their manufacturing. One is the escalating trade war between the US and China. “I think that driver is really what accelerates all the conversations,” Swan said at the summit. Experts don’t see a quick resolution on the horizon, and the fashion industry is settling in with the expectation that the tariffs the US is placing on goods imported from China are here for the long term.

More broadly, in a highly competitive market that’s splitting ever more into winners and losers, a fast, flexible supply chain is increasingly an advantage. It allows brands to respond better to the needs and wants of today’s demanding, internet-enabled shoppers, and it’s why brands including Nike, Adidas, Levi’s are changing the way they make their products—and investing in things like automation and moving production nearshore.

Ultimately, it’s not so much a question of whether garment production will move away from China and closer to Western markets, but rather how much of the supply chain will be rerouted, and when.