Beijing goes hunting for overseas real estate bought with dirty money

Seizing Bo Xilai’s French villa may be just the beginning.

Seizing Bo Xilai’s French villa may be just the beginning.

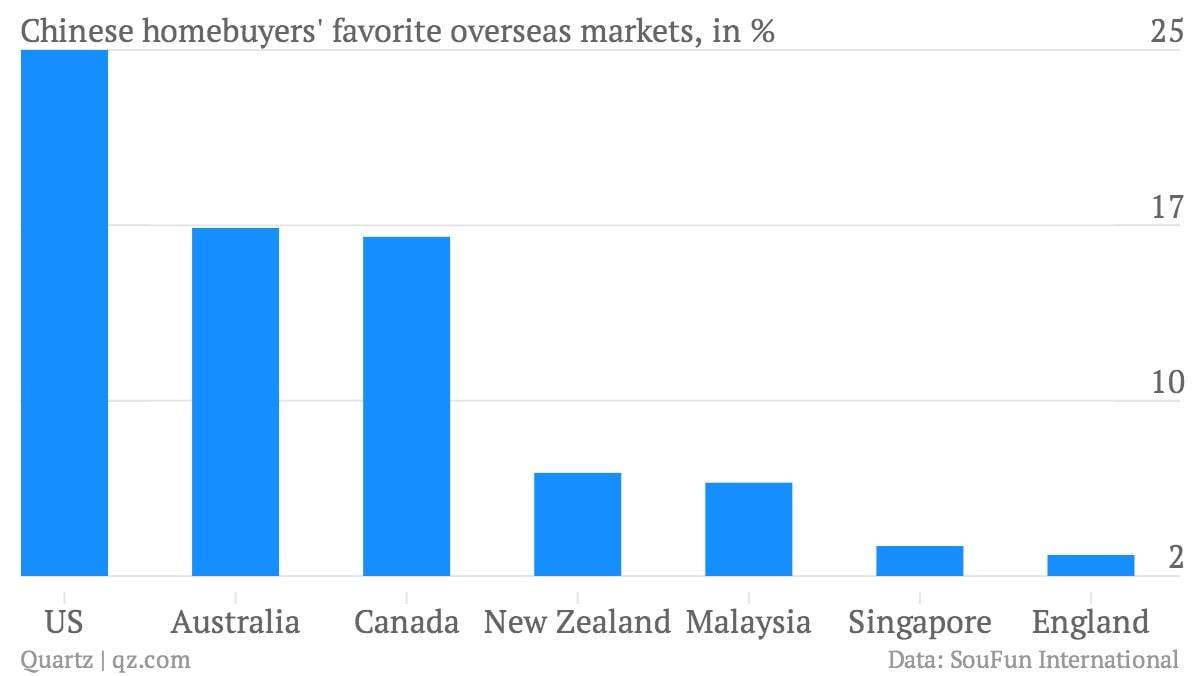

China’s corrupt officials and crooked businessmen have smuggled billions of dollars overseas, much of which has ended up in real estate in the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom—particularly in high-end neighborhoods in London, New York, Los Angeles, Sydney and Toronto. Now the Chinese government is embarking on a worldwide hunt to seize the properties with help from foreign governments, according to asset recovery and anti-corruption specialists.

Since Wang Qishan, the Communist Party chief tapped to head China’s new anti-corruption drive, took office last fall, he has been pushing to crack down on capital flight from the country. In recent months, Chinese officials have quietly said they are specifically targeting foreign assets, and sought help from organizations like the OECD, anti-corruption groups and the foreign government agencies including the US Commerce Department about their newly aggressive pursuit of overseas real estate.

Chinese officials “are interested in understanding where the assets are” in the US, and “the US has said it will work with them,” said Nathaniel B. Edmonds, a former Department of Justice official and a partner with the Washington DC law firm Paul Hastings. In July, Canada and China agreed to seize, share and return the proceeds of crime.

Beijing’s interest in hunting down the proceeds of corruption takes place amid a similar push around the globe, with countries like Libya seeking to take back the assets that their corrupt officials have squirreled away. “There is an increased push to use asset recovery mechanisms in the context of corruption globally,” said Faisal Osman, a barrister with the London firm ARM Stolen Asset Recovery.

Following the money

President Xi Jinping’s corruption crackdown has resulted in a surge of convictions—in the first quarter of this year alone, China’s prosecutors handled nearly 3,700 corruption cases involving $87.5 million. And the campaign has claimed some prominent scalps, many of which involved prominent foreign property holdings. When the Jinan People’s Court sentenced former Politburo member Bo Xilai to life in prison in September, it also announced plans to seize a villa owned by his wife on the French Riviera. Separately, a home in Walnut, California, believed to be owned by ex-railway minister Zhang Shuguang, is also a likely target for Beijing’s asset hunt.

Those high-profile cases may be just the beginning.

Estimating exactly how much corruption-tinged cash has fled China in recent years is difficult, but Ran Liao, senior program coordinator for Transparency International, a non-profit that works with governments and the private sector to curb corruption, said estimates run as high as 500 billion yuan ($82 billion) taken overseas in recent years. Other mind-boggling estimates abound:

- A leaked report from China’s central bank estimated that from the early 1990s to 2008, some 18,000 officials and employees of state-owned enterprises pilfered a total of 800 billion yuan ($123 billion) from state coffers, with the culprits most likely to flee to the US, Canada, Australia and the Netherlands.

- China’s anti-corruption unit, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, predicted in another leaked report (link in Chinese) that $1 trillion may have fled China in 2012.

- “Grey income”—household revenue above what’s declared officially—reached an estimated $1 trillion in 2011, according to the China Society of Economic Reform.

For a corrupt official with money to invest, putting funds directly into an overseas bank or stock market can be risky, because financial institutions are required by global anti-money laundering agreements to report suspicious funds. But real estate agents in most countries have no such requirements. So when Chinese buyers land with suitcases full of cash, as they have in recent months, real estate deals can get done quickly.

Chinese buyers spent $30 billion on overseas real estate in 2012, estimates Juwai.com, a property website. Of that, $9.1 billion went to the United States and much of it specifically to California. And almost 70% of the purchases made by Chinese buyers in the United States were made entirely in cash, according to the most recent report from the National Association of Realtors.

Australian regulators approved $4 billion in real estate purchases by Chinese investors in the 2011/12 fiscal year (pdf, pg. 30), the most recent figures available. Canada keeps no hard data about foreign investors in real estate, but Chinese buyers in one year outnumbered local buyers in Vancouver by a three to one margin. They also bought 27% of new homes sold in London last year.

Hunting “naked officials”

The soon-to-retire Chinese bigwig who has stashed money and relatives abroad in preparation for his escape is such a common character in China that it has its own phrase: luo guan, or “naked official.”

Some of them have laid the groundwork for years; one common ploy is to send a son or daughter overseas to a private university as a way to legitimize sending funds out of China. For example, the leaked Chinese central bank report on corruption showed that former ministry of finance official Xu Fangming deposited roughly 1 million yuan ($164,000) into the bank account of a son studying abroad. Perhaps not coincidentally, the number of Chinese students studying abroad has jumped in recent years. In the United States, it more than doubled to 194,000 in the 2011/2012 school year from five years ago.

Another popular strategy for gaining a foothold overseas is securing a foreign passport through “immigrant investor” programs.

The ultimate goal in transferring money out of China, said Transparency International’s Liao, is that either the official or his offspring will have a happy life after they leave China. The new crackdown on overseas assets is designed to stop this process.

“The government wants to make them hopeless,” Liao said. The message is “You can’t just steal money from China and then enjoy life in Canada.”

A tough road to recovery

Whether the Beijing’s hunt for overseas properties will be a success, and perhaps even impact home prices in Los Angeles or London, remains to be seen.

Seizing and recovering assets in a foreign country can be a tough slog for any government, experts in the field say. While China and most Western nations are signatories to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, in which countries pledge to help each other recover the stolen funds, the process is lengthy, arduous, and fraught with diplomatic and legal complications.

In the United States, for example, the party hoping to seize a home needs to prove that it was purchased entirely with funds derived through corruption. “In drug-related cases you seize the house and the car,” quickly and authoritatively, said Edmonds. But corruption-related cases are often more complicated, because tainted funds are mingled with other, legitimate, funds, he said.

Another glaring vulnerability in any US-Chinese cooperation on asset seizure is the lack of a “Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty” between the two countries, which allows governments to seize foreign assets related to crime, said Daniel F. Roules, a Shanghai-based partner with Squire Sanders. That means Chinese authorities need to rely on cooperation from their US counterparts.

And while US government officials have pledged to help, Laio of Transparency International said that Chinese officials he’s spoken with aren’t getting as much assistance as they would like. The US State Department and Department of Justice declined to comment.

Jurisdiction shopping in Britain

British courts, on the other hand, see themselves as “world leaders in asset recovery,” Osman said, because there are powerful laws on the books, a long line of precedents and relatively straightforward laws.

A 10 million pound ($16 million) home in Hampstead Garden Suburb, a wealthy London neighborhood, purchased by Saadi Gaddafi, son of the deposed Libyan dictator, was seized in 2012 by the Libyan government after British courts ruled that Saadi could not have made enough money to purchase it on his military salary. Often officials hoping to pursue property they believe was purchased by the fruits of corruption will “get a judgment here [in the UK] and get it enforced in another jurisdiction,” Osman said.

A UK judgement can sometimes be used successfully in the United States, as it was to seize a mansion in Houston and two Merrill Lynch brokerage accounts belonging to Nigerian governor James Onanefe Ibori.

Whether the Chinese campaign to halt corruption and seize overseas assets will have real impact on property markets in the United States, Australia and Canada has less to do with international laws than it does what happens in Beijing in coming months.

“What it comes down to is political will,” said Osman. Given the changing winds of politics, a push towards recovering assets of one person or group can sometimes be halted abruptly. “These by their very nature are lengthy proceedings and sometimes the political will fades,” he said. In one case he worked on involving a South Asian country, “the guys’ assets we were tracing a few years ago are now the guys in power.”

Ivy Chen and Jennifer Chiu contributed reporting.