Germany doesn’t care if everyone hates its export model

Germany’s economic model has been getting rotten tomatoes thrown at it from all angles lately. Late last month, an official US Treasury Department report criticized German unwillingness to boost domestic spending to support demand within Europe’s largest economy. When German officials protested, calling the criticism “incomprehensible,” they received a series of high-profile public lectures from some of the world’s top Keynesian pundits including Paul Krugman and Martin Wolf.

Germany’s economic model has been getting rotten tomatoes thrown at it from all angles lately. Late last month, an official US Treasury Department report criticized German unwillingness to boost domestic spending to support demand within Europe’s largest economy. When German officials protested, calling the criticism “incomprehensible,” they received a series of high-profile public lectures from some of the world’s top Keynesian pundits including Paul Krugman and Martin Wolf.

Their take is pretty straightforward. Since Germany is one of the few countries in a position to spend—thanks to its large current account surpluses—it should act to boost German domestic consumption by borrowing and spending more. (It would be cheap to borrow, with interest rates an near historic lows. And there’s plenty to spend on, like basic upkeep on roads, bridges and railways, as Germany has been underinvesting for years.) A more buoyant German economy would provide a source of demand for its troubled European neighbors as well as lift to the global economy overall.

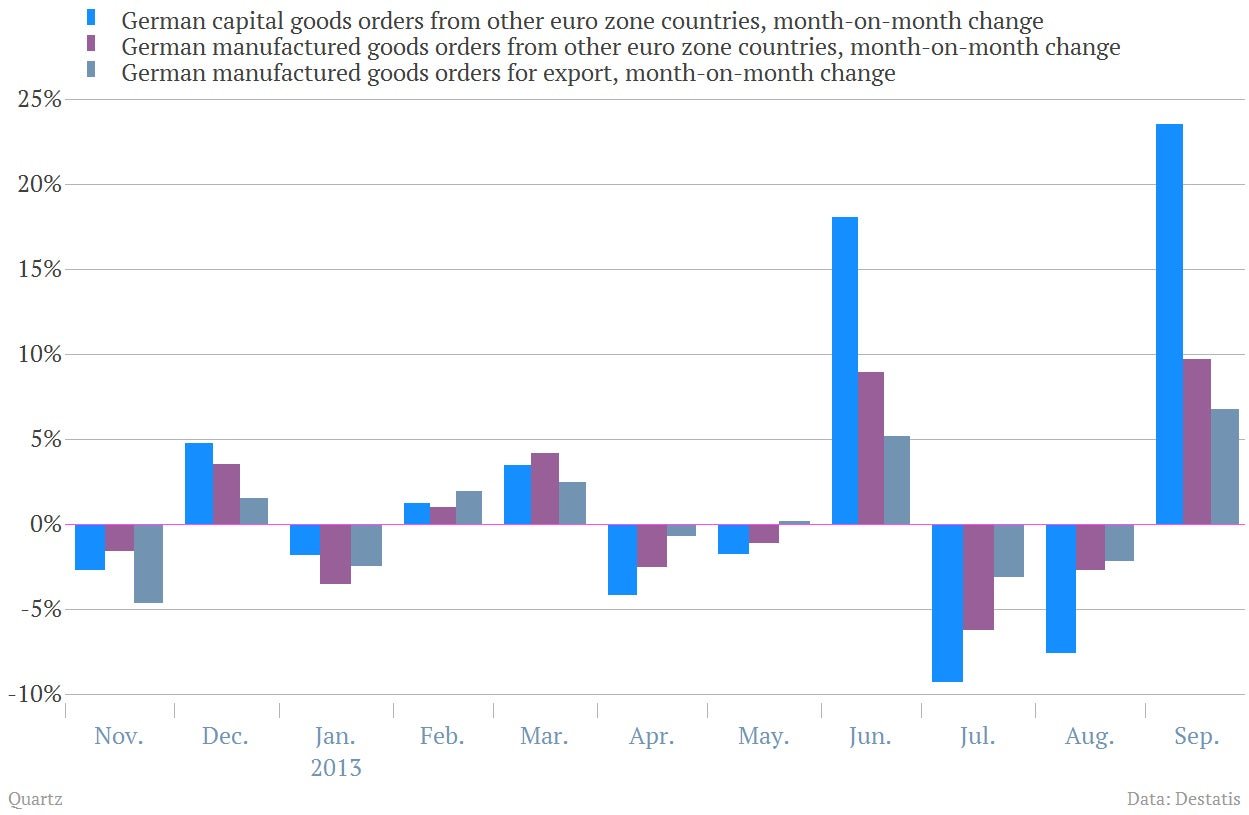

Germany has shown few signs of being swayed by such arguments. (Revelations that US cyber spies tapped Chancellor Angel Merkel’s phone haven’t made WHO any more likely to take economic tips from the Americans any time soon.) And from the German perspective, its system of reliance on exports seems to be muddling ahead just fine. For instance, German manufacturing orders jumped 3.3% in September, according to data out this morning, which was better than expected. Driving the growth was a 10% month-on-month increase in demand from other euro zone nations. That included a nearly 24% rise in capital goods orders from other euro zone countries.

Today’s numbers aside, Germany shouldn’t kid itself. Demand from its euro zone trading partners is nowhere near what it was before the Great Recession and the European debt crisis. And big Germany companies have been tightening their belts significantly over the last year. (The most recent example was Siemens’ announcement that it will axe around 15,000 jobs.) German unemployment rose a much higher-than-expected 24,000—though the unemployment rate was unchanged at 6.9%—in September, too. Of course, it would take a much sharper deterioration of the employment picture to force German policy makers to rethink their approach to growth. But that doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen.