Spain faces staggering losses as it accepts the reality of the housing bust

Spain is biting the bullet and starting to recognize the staggering level of losses associated with its housing bust.

Spain is biting the bullet and starting to recognize the staggering level of losses associated with its housing bust.

Fitch Ratings analysts who watch the market for Spanish mortgage bonds—packages of home loans that are sold off to investors—say financial institutions are starting to unload repossessed properties at a faster pace. During the first half of the year, 44% of repossessed properties had been sold, compared 31% at the end of last year.

Now bear in mind there are very few people in Spain who even want to think about buying a house. (Spain’s economy is in horrific shape. Unemployment is perched at more than 26%, and about 4.8 million people are jobless.) So in order to sell these properties, prices have to come way down.

This is a painful process of recognizing an ugly real estate reality: There are far more houses than buyers. The result? Sales of repossessed properties were on average done at prices 71.5% lower than where the houses were originally valued. That means the average price for a house that was originally sold for €100,000 in say, 2006, repossessed and then sold during the first half of 2013, would have brought a price of €28,500.

“This trend is indicative of a willingness to offload properties in possession more quickly and to accept deeper discounts,” Fitch analysts wrote.

You could argue that that this is a good sign. When you have a banking collapse, which Spain did, the banks at some point have to recognize the full extent of their losses and build a new stable base of capital that they can use to start lending again. (If banks don’t lend, developed economies have a very difficult time growing.)

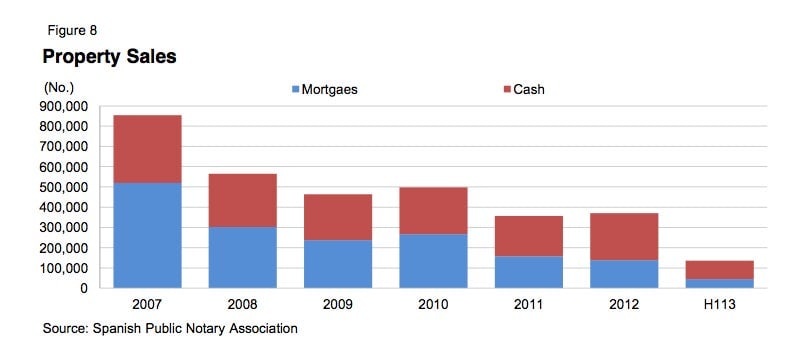

But Spain is really just starting this process. With few buyers, the pace of sales is incredibly slow.

Sareb, the country’s government-owned “bad bank,” created in 2012 to take the most toxic properties off the hands of the banks, is already looking like it will miss its target of selling off some 45,000 houses over the next five years.

That’s because it faces a very tough balancing act. If it sells the houses for discounts that are too deep, it risks collapsing what’s left of the housing market. (Not to mention inflicting new losses on the banking system and itself, which might require another embarrassing trip to the European powers-that-be with hat in hand.) On the other hand, if Sareb refuses to let prices fall to the level that encourages buying, it’s doing very little to help Spain get back on its feet.

So what’s the answer? Basically, the size of Spain’s banking crisis required a bigger, politically unpalatable bailout from the European policy makers writing the checks. The only other option is to allow Spain to slowly grind through its national real estate losses and let the banks try to absorb them over time, a process that stifles lending and chokes off economic growth.

This approach is the one Japan chose after its own real estate bubble busted in the early 1990s. It’s a recipe for decades of terrible economic conditions. But that seems to be what Europe is cooking up.