A giant crater found in Greenland might be the key to an unproven extinction theory

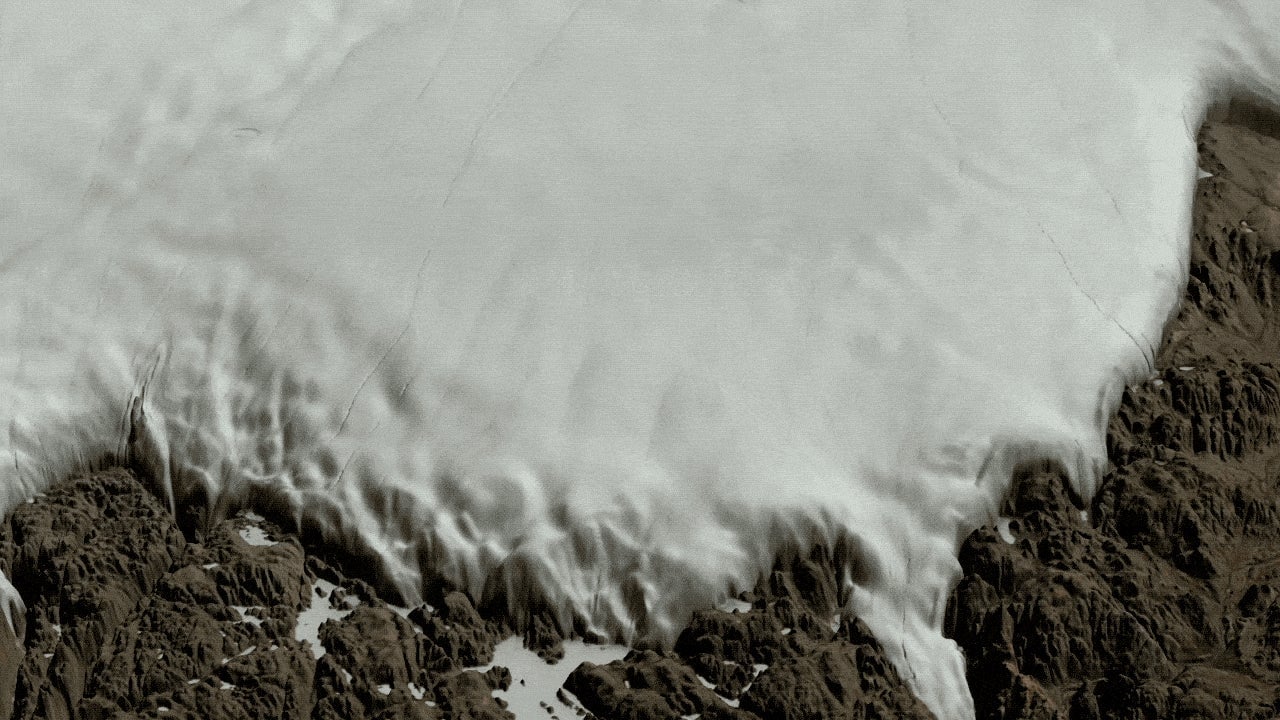

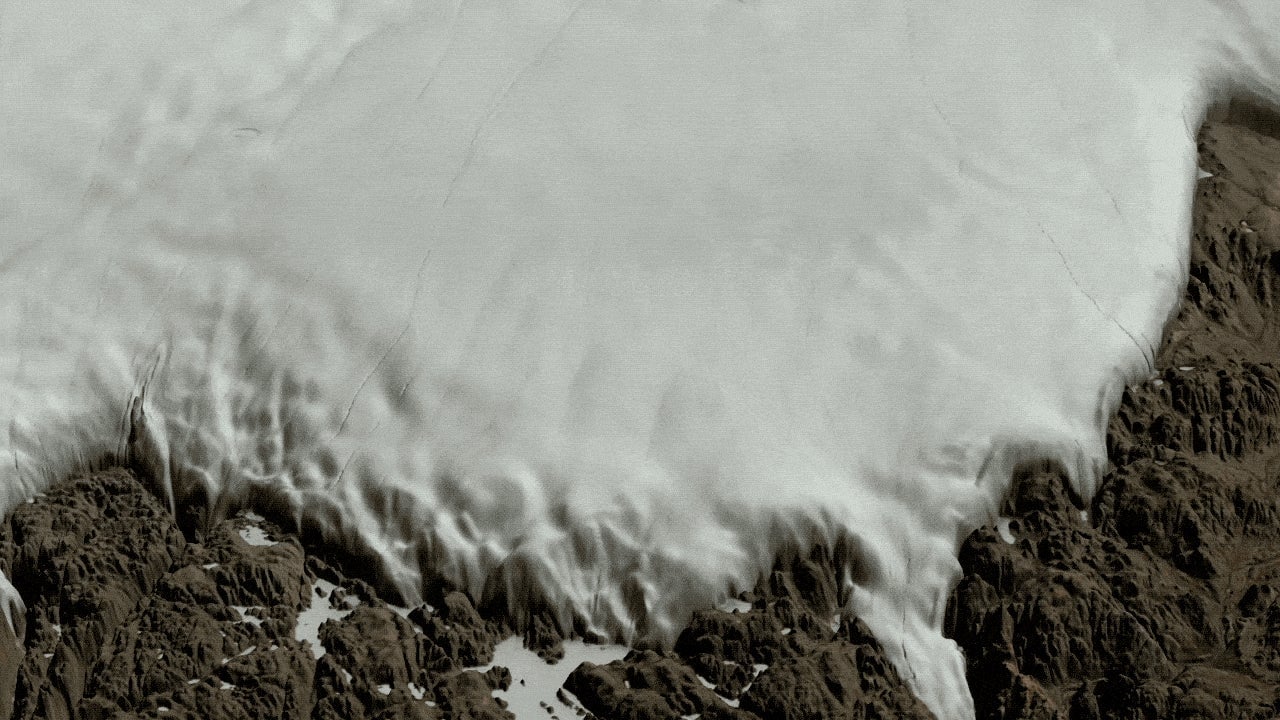

Buried a half-mile deep under the icy plains of Greenland’s Hiawatha Glacier, scientists have discovered a giant crater. Nearly 20 miles wide, the crater is among the 25 largest in the world; for scale, NASA says it’s a bit bigger than the Washington, DC Beltway area.

Buried a half-mile deep under the icy plains of Greenland’s Hiawatha Glacier, scientists have discovered a giant crater. Nearly 20 miles wide, the crater is among the 25 largest in the world; for scale, NASA says it’s a bit bigger than the Washington, DC Beltway area.

Danish scientists first spotted the crater when reviewing topographical data in 2015, but it took some time to confirm, since it’s buried under 3,000 feet of ice. After examining additional satellite imagery and radar data collected during a fly-over of the area, the team was convinced of their discovery, which was published this week in the journal Science Advances.

Based on the shape of the crater and the sediment found in nearby glacial runoff, the scientists believe that the crater was likely caused by a meteorite strike less than 3 million years ago, possibly near the tail end of the Earth’s last ice age a mere 13,000 years ago. At its deepest point, the crater is around 1,000 feet below the surface of the ground, which means the meteorite could have been more than half a mile wide.

That has some scientists excited. A meteorite big enough to create the Hiawatha crater would also have disrupted life on Earth for centuries. Some researchers believe it could be the missing piece of a decade-long theory about why woolly mammoths, giant sloths, and early humans of the Clovis culture died out. Based on geological analyses, scientists believe that a 1,000-year-long cooling event called the Younger Dryas began around 12,800 years ago, and according to one theory published in a 2007 paper, the Younger Dryas was caused by “an extraterrestrial impact event.”

While the authors originally theorized the impact took place somewhere in North America, no one could find the crater in question, but it’s possible that this new Greenland discovery could be it. “I think we have the smoking gun,” geochemist Wendy Wolbach told Science Magazine.

But the paper’s lead author is reluctant to jump to conclusions, as exciting as they may be. “We do not discuss it in the paper, but I think it is a possibility,” geologist Kurt Kjær told National Geographic. “This may generate a lot of discussion, and we need to find out.”