The 26-foot-long “unicorn of the sea” is a lesson in the wonders of collaboration

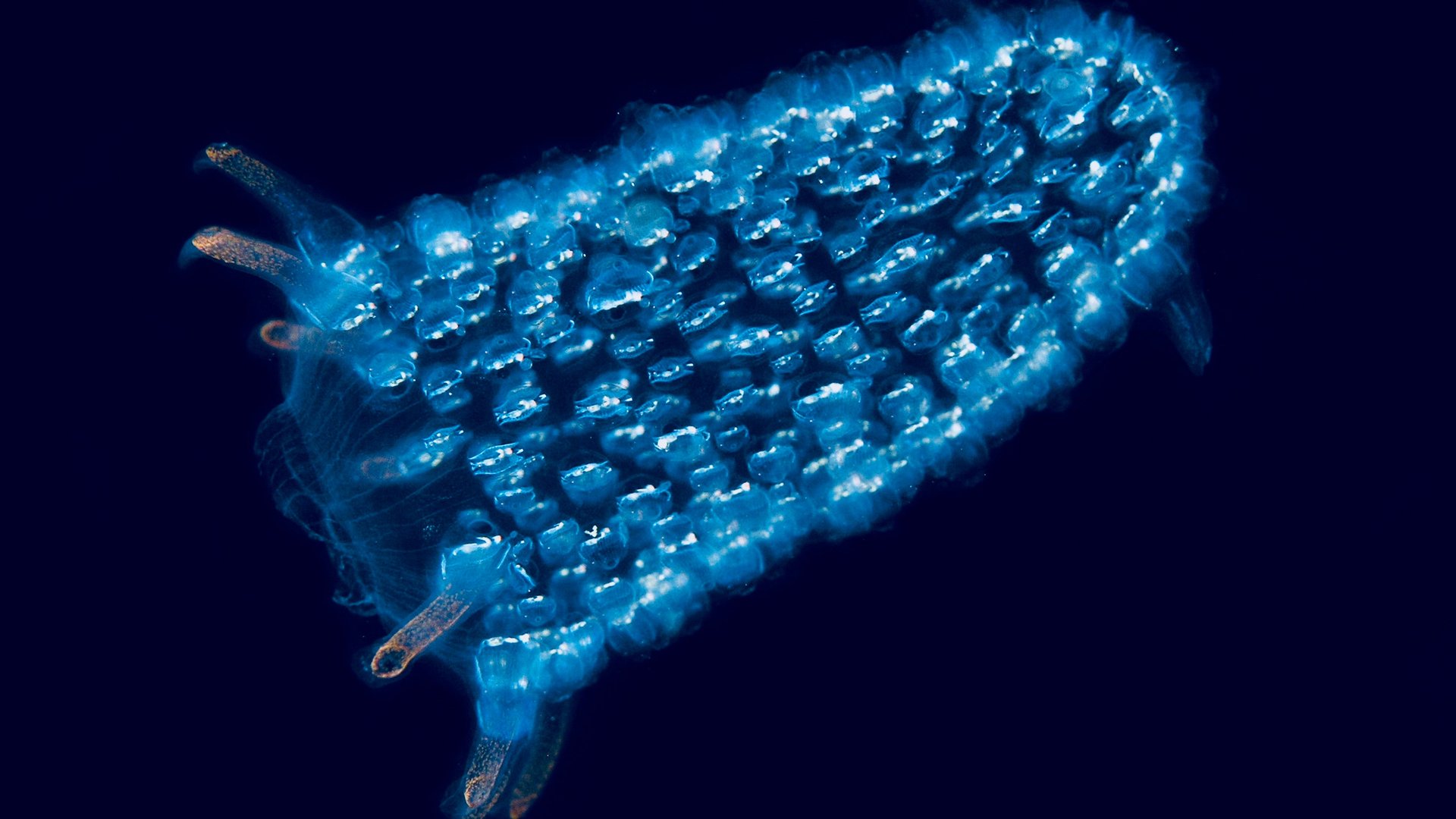

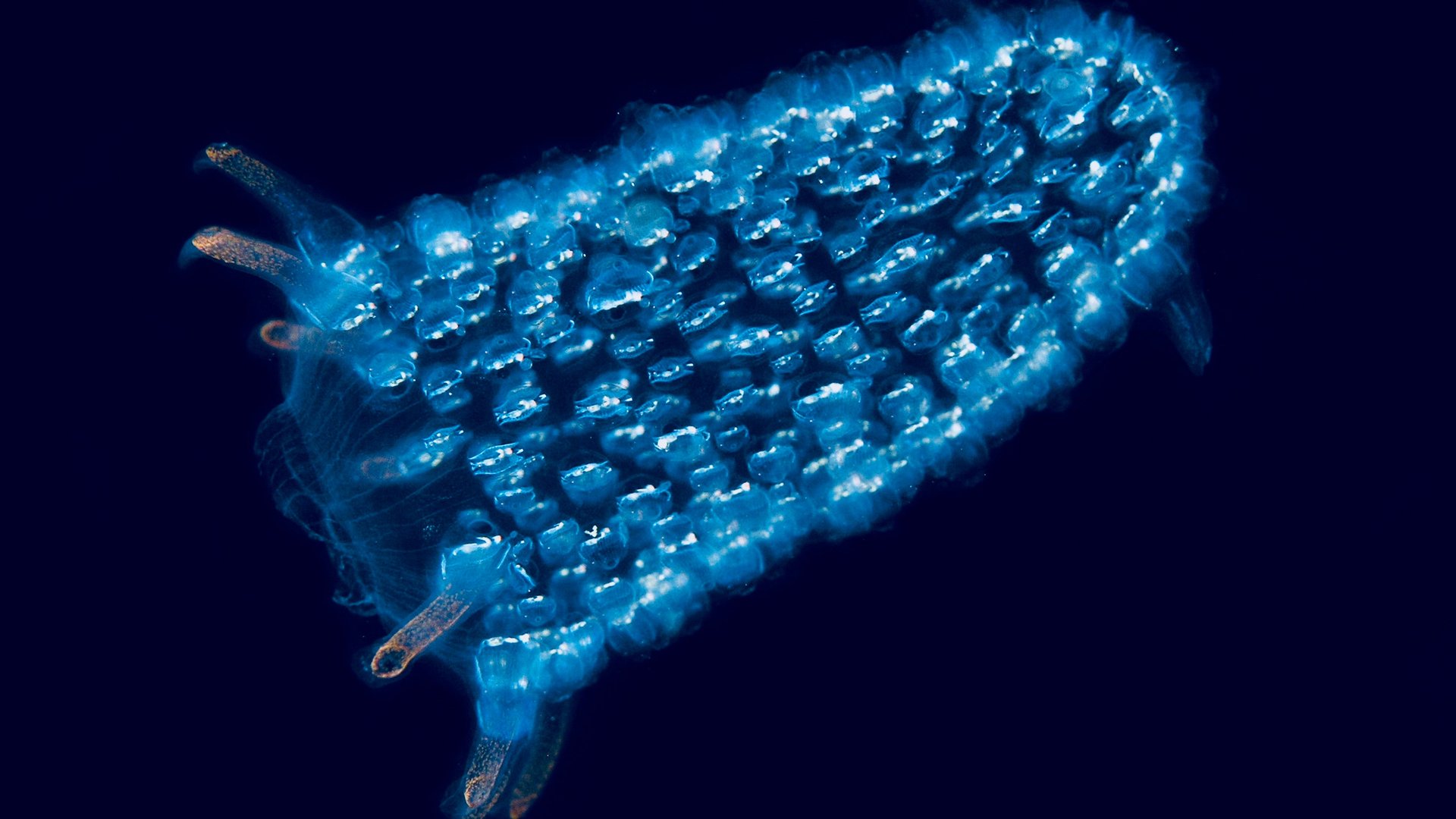

Pyrosomes, also known as unicorns of the sea, are exceptional evidence of the advantages of cooperation. These colonies of creatures, made up of hundreds or thousands of individual organisms known as zooids, travel together in a single gelatinous tunic.

Pyrosomes, also known as unicorns of the sea, are exceptional evidence of the advantages of cooperation. These colonies of creatures, made up of hundreds or thousands of individual organisms known as zooids, travel together in a single gelatinous tunic.

Alone, each zooid is an unimpressive, negligible entity—merely millimeters long. Together, they are an intimidating force, extending up to 60 feet.

One such creature was recently spotted and caught on camera by videographer Steve Hathaway. The pyrosome sighting occurred on Oct. 25. It was a 26-foot long sock-like colony seen near the small, volcanic White Island, 30 miles off New Zealand’s northernmost point. For Hathaway, this strange vision was a dream come true. “I’ve always wanted to see one,” he tells The Washington Post. “This was beyond exciting.”

Indeed, if marine biologists are to be believed, pyrosomes are a sight to behold. “I was living in Africa the first time I saw a pyrosome, and I nearly cried,” writes researcher Rebecca Healm in Deep Sea News. “I actually gasped in recognition. My first real life pyrosome. Among many marine-inclined folks such as moi, pyrosomes are like unicorns. Completely improbable, utterly mysterious.”

Pyrosomes gained this awesome reputation among scientists because they have science fiction-like qualities. “If the Borg and the Clone Wars had a baby it would be a pyrosome,” Healm explains. Each tiny zooid can clone itself, and the lot of them function as one unit, much like Star Trek’s mentally-connected Borg. But pyrosomes—unlike Seven of Nine and the Borg hive mind—are physically linked. They share tissue. They are distinct, and yet they are one.

“The whole colony is shaped like a giant thimble with a point on one end and an opening on the other, and in some species this opening can be up to 6 feet wide–large enough to fit a full grown human inside,” Healm writes. That doesn’t mean viewers lucky enough to spot one should be tempted to squeeze in: ”Do not swim inside a pyrosome,” she warns.

The glowing pyrosome can be a danger to the unwary. Based on one researcher’s observations, a creature that gets stuck inside a pyrosome may not reemerge and certainly not alive. K Gowlett-Holmes of CSIRO Marine Research in Australia reports finding a 6.5-foot long pyrosome with a dead penguin trapped inside. “The penguin had obviously swum in the open end of the tube then couldn’t turn–it was jammed in the apex of the pyrosome and its beak was just poking through the colony matrix…the fact it could not break free shows just how tough some pyrosomes are,” Gowlett-Holmes states on Deep Sea News. The penguin apparently suffocated inside the pyrosome, unable to escape.

These giant colonies fall into a category of creatures known as “pelagic sea squirts.” They are pelagic, or free-swimming, and consist of a conglomerate of sacks that are individually referred to as sea squirts.

Each zooid uses two siphons through which water enters and exits. Individual zooids eat tiny plankton, and they constantly suck water in and blow waste out while moving. The sucking and blowing propels the lot of them forward, somewhat like a jet propulsion engine, only with no gas and no engine.

To add to the wonder and creepiness of these creatures, pyrosomes are bioluminescent, and so the travelers also glow in the ocean. The name pryosome stems from the Greek words for fire, “pyro,” and body, or “soma.”

Plus, these fire-bodied colonies, which swim in the warm waters of the world’s seas, are apparently rather chatty to boot, using light as their language. “Each individual zooid is capable of emitting light, and when one does it, the neighbors do too,” writes Joseph Jameson-Gould on Real Monstrosities. “Sometimes light from one colony will cause a whole other colony to start lighting up. It’s as if they’re communicating…talking…discussing.”

Really, it’s no wonder that creatures who share a wardrobe and a purpose while traveling in a gelatinous tunic together would communicate amongst themselves, and perhaps even with other similar colonies. After all, communication is what makes collaborations successful. These pyrosomes are obviously committed to cooperating as they propel luminously and creepily through the sea as one connected being.