If China lets its people have more children, it could have trouble feeding them

Following a high-level meeting this week, there are once again reports that China will soon announce reforms to its one-child policy, which has been called invasive, socially destructive, and unnecessary. (It affects about one-third of the country; families in rural areas, ethnic minorities, and couples where both parents are single children are often allowed to have more children.)

Following a high-level meeting this week, there are once again reports that China will soon announce reforms to its one-child policy, which has been called invasive, socially destructive, and unnecessary. (It affects about one-third of the country; families in rural areas, ethnic minorities, and couples where both parents are single children are often allowed to have more children.)

But officials—perhaps to defend the 30-year-old policy’s utility in the past—are trotting out age-old arguments in its favor. Key among those is that without strict population control, China wouldn’t have had enough resources to develop so quickly and so impressively. If not for the one-child policy, China would have 400 million more people and “per capita ownership of resources, including arable land, grain, forests, drinking water and energy, would be 20 percent less than what it is today” Mao Qun’an of China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission told reporters on Nov. 12, the same day the party’s Third Plenum meeting ended.

Mao’s calculations are debatable. Most academics question the government’s claim that it prevented 400 million births. But his comment does underline the conflicting needs of China’s natural resources and its human resources. As we’ve written, even if one-child rules were overturned today, leading to an estimated 9.5 million more babies a year, those babies wouldn’t grow up fast enough to replenish China’s shrinking labor force or take care of the growing ranks of the elderly. But that does mean China would have 9.5 million more people every year who need food, water, and housing.

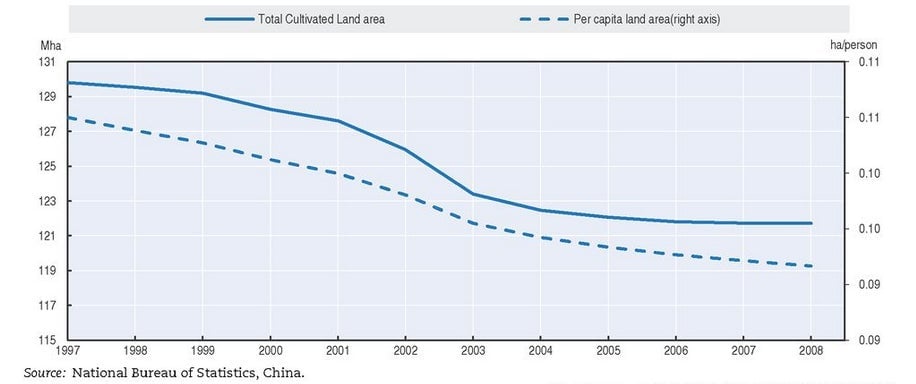

A range of issues make that difficult. Already, per capita arable land in China is half of the global average (pdf, p. 79). Pollution, erosion, and the transformation of rural areas into cities as part of China’s urbanization drive mean 40% of that arable land (p. 80) is considered “degraded” by the United Nations, meaning that it is less economical or uneconomical to farm. Also, the movement of young workers from rural areas to cities means there are fewer people (p. 78) to invest in farming technology to improve productivity, the UN warned earlier this year.

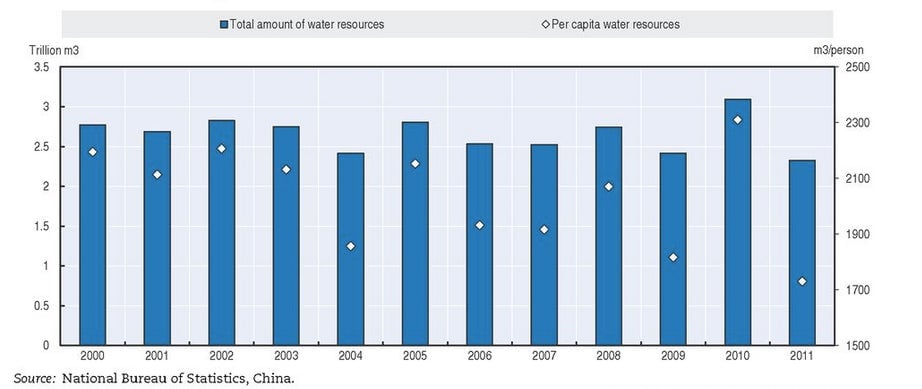

On top of that, China lacks water for drinking, manufacturing, and producing energy, because it’s been depleting its groundwater and river sources, especially in the north. Today, China has 20% of the world’s population but only 7% of its fresh water supplies. The government has warned that demand for water might outstrip supply by 2030.

A day before the Third Plenum, Mao also said that the government plans to simply “fine tune” the one-child policy. Given the dire condition of China’s farmland and water supplies, and its officials’ inclination for faster economic growth, a fine-tuning may be the best we can expect.