China’s decades-long one-child policy is credited with helping China’s economy grow, but many Chinese resent it bitterly, and there already several exceptions to the rule. Now the authorities are studying the possibility of relaxing it for most Chinese.

In many provinces, parents without siblings are already allowed to have more than one child. Other exceptions include ethnic minorities and often couples in rural areas. But now, according to state news agency Xinhua, China’s national health and family planning commission is considering allowing any couple where one parent is an only child to have two children. This would effectively suspend the one-child rule for many more urban couples, the largest group affected by the policy. Some anticipate the reform will be announced in the fall at the National People’s Congress, when key economic reforms are often unveiled.

Chinese media report (link in Chinese) that authorities are also considering allowing all couples to have two children after 2015. If that happens, China’s population would increase by an estimated 9.5 million more babies (link in Chinese) each year over the first five years, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch in a note over the weekend. Over the course of 30 years, the Chinese government says the policy has prevented 400 million births that would have been. So what would more babies mean for the economy?

A larger labor force—eventually

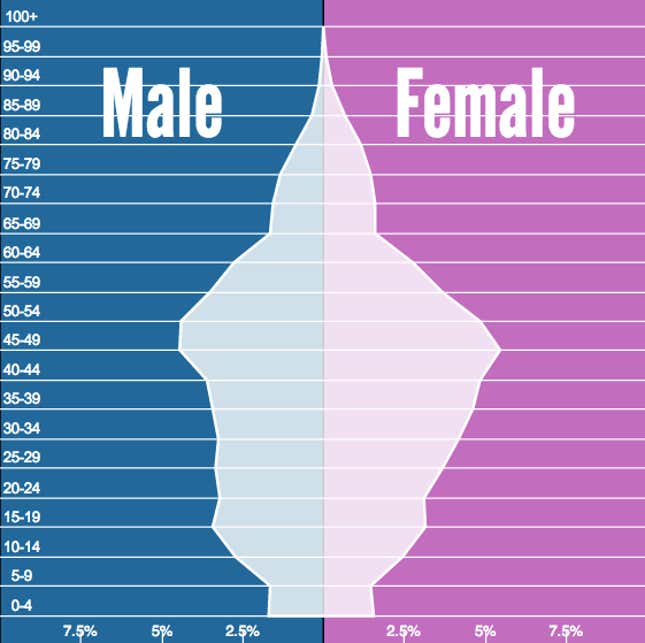

China’s approximately 930-million-person labor force shrank last year for the first time in decades, and will decline further as a population bulge of people now in their 40s and 50s pass into retirement. Here’s how that looks:

A baby boom would help compensate, and increase the number of people who can support that aging population. However, it may be too little too late, given that the labor force is estimated to begin declining by as much as 10 million a year starting in 2025, and it will take at least 16 years for the effects of a baby boom that starts today to be felt in the workforce. The authorities may be unable to avoid unpopular measures like raising the country’s retirement age—55 for women and 60 for men.

A little bit more consumer spending

Allowing more couples to have more children now should boost consumption almost right away. Demand for baby related products like infant formula, food and clothing, and services like education has been increasing in China. Tilting the economy more towards domestic consumption is a core of the government’s strategy to forestall slowing economic growth.

However, China’s fertility rate is already low and may not budge much even if the policy is changed. (In 2011, China’s fertility rate—the number of children a woman can expect to have—was 1.4, below the needed replacement rate of 2.1.) As more families live in urban centers, couples might still opt out of having more children. ”When families urbanize they do not have two, three children. That is not the pattern in Asia,” Ted Fishman, author of China Inc told Bloomberg (video). ”China wants to be more than 50% urbanized, eventually 80% urbanized. You won’t get that 400 million number even if China liberalizes the one-child policy.”

Happier people

Perhaps the more important effect of changing the one-child policy is that it could end human-rights abuses like forced abortions and signal that the leadership is serious about reforms in general. “We believe that the reform-minded president Xi and premier Li will use the opportunity of abolishing the one-child policy to build up their authority, show their determination in making changes and convince the Chinese people that they do have a roadmap for reforms,” wrote Bank of America China economists Ting Lu and Xiaojia Zhi in their note over the weekend.