The first interplanetary cubesats pave the way for cheaper space science

When NASA’s latest science mission landed on Mars, the space agency was able to track its progress in real time and capture an immediate image of the Martian surface thanks to a pair of tiny satellites that could change the way humans explore the solar system.

When NASA’s latest science mission landed on Mars, the space agency was able to track its progress in real time and capture an immediate image of the Martian surface thanks to a pair of tiny satellites that could change the way humans explore the solar system.

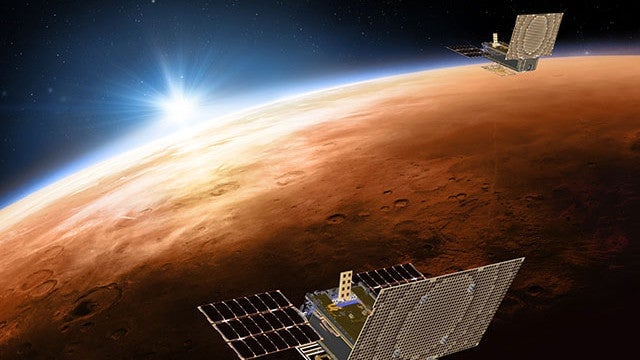

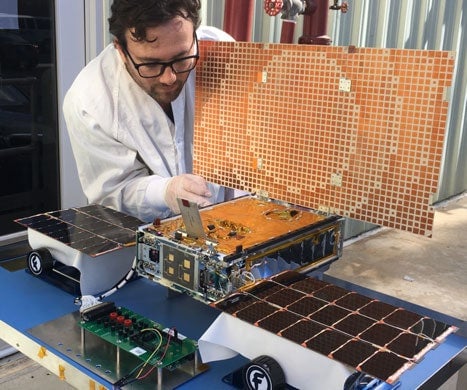

Two cubesats—miniature spacecraft weighing just 30 lbs (13.5 kilograms) each—were launched alongside Mars InSight, the probe that landed on the red planet today (Nov. 26). While these tiny satellites have proven increasingly useful in orbit close to Earth, this was the first mission to deploy them in deep space.

The role of the Mars Cube One demonstration was to relay radio transmissions from the probe as it entered the Martian atmosphere and slowed itself to land. This included recording its speed and when InSight deployed its parachutes and locked on with the radar that guided it to the ground.

Absent the two satellites, known as MarCO-A and MarCO-B, the control team working at Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Lab would have been waiting for a single ping from the lander to notify them of a safe landing.

Now, as the cubesats continue on into deep space and Mars rotates, mission controllers are still waiting for the news that the lander’s solar panels have unfolded. That’s expected at about 5 pm ET. It will be the final sign that the lander can sustain itself for the extent of its research mission.

The success of the two cubesats suggests cost efficiencies that led the NASA and JPL-influenced start-up Planet to become the world’s largest commercial satellite operator in just eight years can now be applied to deep-space exploration.

Thomas Zurbuchen, the NASA executive in charge of science missions, has proposed spending $100 million a year on cubesats. NASA hopes this expenditure will provide outsized returns along with more traditional multi-billion-dollar missions like the James Webb Space Telescope, which often face years of delay compared to the deployment of more nimble small satellites.

For now, NASA’s deep-space scientists will focus on the geological data collected by Mars InSight, which is expected to start returning data in March 2019.