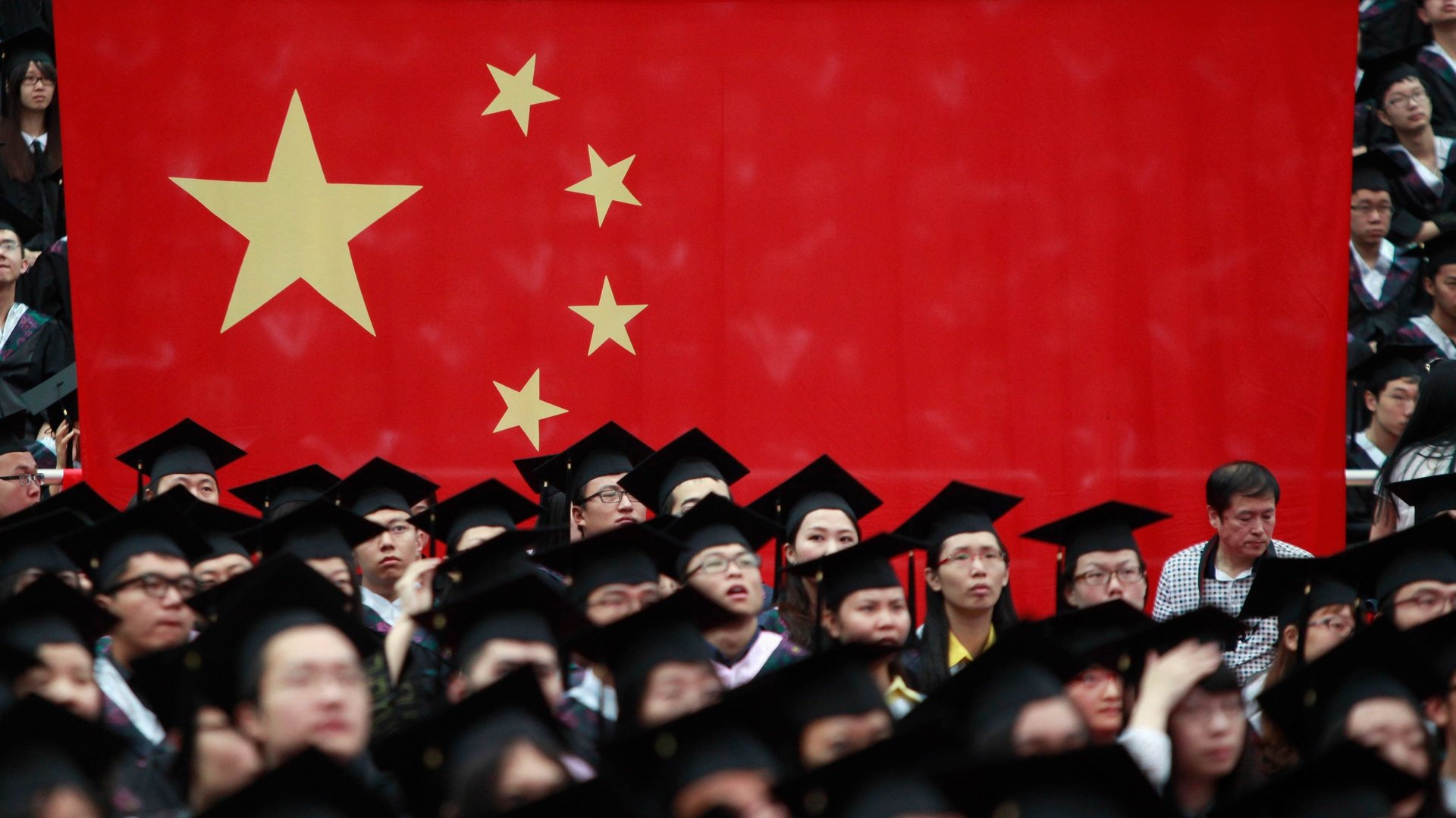

For the first time, a US college is insuring itself against a drop in Chinese students

Chinese nationals account for the largest share, about 30%, of all foreign students who require a visa to study in the US (including undergraduate and graduate university students, as well as some primary and secondary school students). Their economic impact is so significant that one institution, the University of Illinois- Urbana-Champaign, has paid to insure itself against a major drop in tuition revenue from Chinese students, Times Higher Education reports.

Chinese nationals account for the largest share, about 30%, of all foreign students who require a visa to study in the US (including undergraduate and graduate university students, as well as some primary and secondary school students). Their economic impact is so significant that one institution, the University of Illinois- Urbana-Champaign, has paid to insure itself against a major drop in tuition revenue from Chinese students, Times Higher Education reports.

The colleges of business and engineering at the university have signed a three-year contract with an undisclosed insurance broker to pay $424,000 annually for $60 million in coverage. The insurance pays out if revenue from Chinese students at the two colleges falls by at least 20% in a single year due to a “specific set of identifiable events,” Jeff Brown, dean of the Gies College of Business at the University of Illinois, told Times Higher Education. “These triggers could be things like a visa restriction, a pandemic, a trade war—something like that, that was outside of our control,” he said.

Reportedly the first deal of its kind in the world, the university conceived the idea in 2015, and entered into the agreement in 2017, but was not given permission by the broker to discuss the contract publicly until now.

The US and China are currently locked in a trade war, and while there is a chance that US president Donald Trump and Chinese president Xi Jinping might reconcile at the G20 summit that starts tomorrow (Nov. 30), growing tensions between the two nations has already impacted Chinese international students. Earlier this year, the US State Department shortened the length of visas granted to Chinese graduate students in certain fields to curb the alleged threat of intellectual property theft. The Trump administration is currently considering even tighter visa restrictions for Chinese students because of growing espionage concerns, according to Reuters.

These new rules would subject student-visa applicants to much more invasive vetting processes than they have in the past. Applicants would have to submit their phone records and social media accounts to officials who would then investigate them for signs of anything that “might raise concerns about students’ intentions in the US,” according to Reuters. Terry Hartle, senior vice president at the American Council on Education, told Reuters that these proposed laws might turn Chinese students into “pawns” in the US and China’s ongoing conflict. The same might be said for US universities—for them, there is roughly $14 billion in annual revenue from Chinese students at stake.

While the University of Illinois’s insurance policy is directly concerned with a drop in Chinese students, falling attendance from other nationalities is also a cause for concern. According to a report from the National Science Board, there was a 6% decrease (31,520 fewer students) in international graduate students between 2016 and 2017, mainly in computer science and engineering, with the biggest drop coming from Indian students.

Public Radio International reports that Indian students seeking to study abroad were repelled by Trump’s immigration policies and increasingly attracted by other countries such as Canada and Australia. “In the US, [international students] are tremendously important” because “over 50% of our graduate students in technical areas are from outside the country,” Geraldine Richmond, a member of the National Science Board and chemistry professor at the University of Oregon, told PRI.

If international students continue to view the US as an unwelcoming place, other institutions might consider seeking insurance policies similar to the one secured by the University of Illinois.